Rütimann, Christioph

Born 1955 in Zurich, Switzerland, lives in Müllheim

Christoph Rütimann once said that the goal of his artwork is to combine the spectra of our perception in order to capture everything that surrounds us. This, of course, is impossible—and Christoph Rütimann knows this, but still he tries. Perhaps this is why his works (drawings, paintings, sculptures, performances, videos, films, installations) always have a tinge of absurdity while engaging in scientific discourse.

From the very beginning, Rütimann has focused on drawing. He draws endless lines on paper or on walls, films this process and then later exhibits the video documents. Elsewhere, he creates extensive drawings on panels made of polyester. He sees drawing as the “primordial language”, which is why he devotes so much time to it. In painting, he is most interested in colours and their interaction. He paints using the reverse glass painting technique, which always incorporates a mirror image of the present.

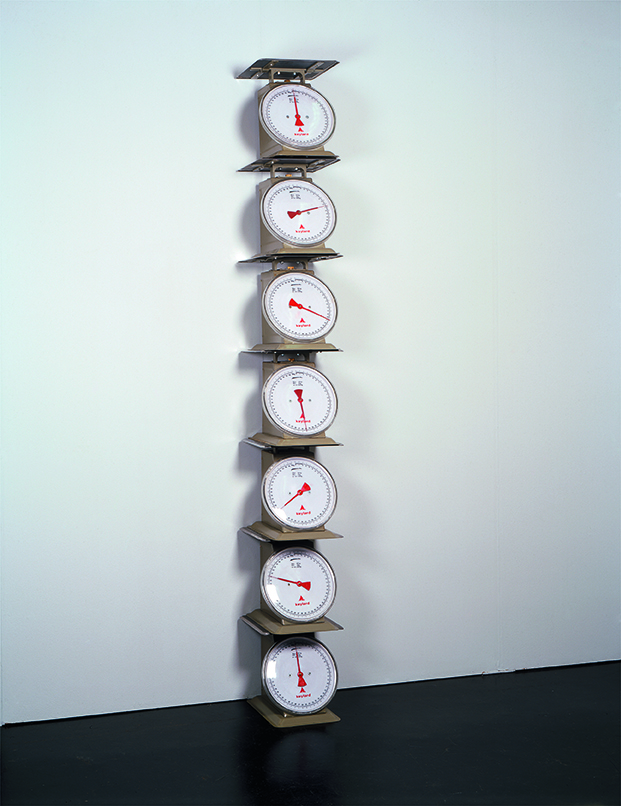

Rütimann’s sculptures take on a more absurd quality and resemble scientific experiments. His favourite sculpting materials are scales and clocks, which he uses to build towers, walls, pyramids and partitions. The scales always show how much load they are bearing. His sculpture 2 Kilogramm 250 Gramm in Gips (2 Kilograms 250 Grams in Plaster) shows a scale being engulfed by plaster. In 2008/2009, he installed PVC piping and cables in the branches of a tree in Hanover which lit up at night to create lines.

Rütimann’s performances are also spectacular. In Lucerne in 1994, he daringly straddled the roof of an old museum to bid farewell to the building, which was slated for demolition. He called the act Hängen am Museum (Hanging on the Museum). In 2002, he repeated this action in front of a crowd on the roof of the new museum built on the same spot by the famous French architect Jean Nouvel.

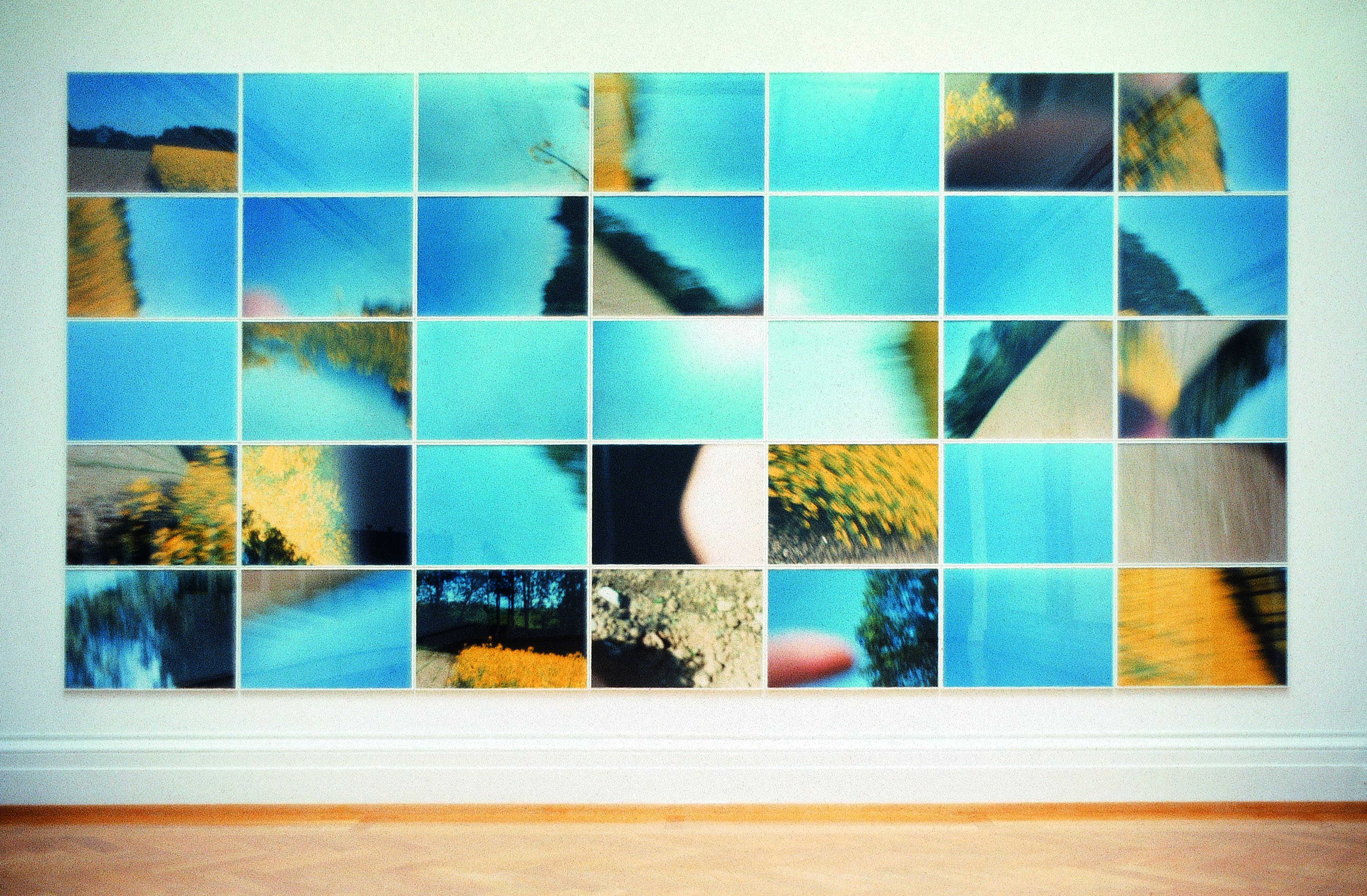

In recent years, in a project entitled Handläufe (Handrails) Rütimann has been mapping European cities with his camera. At an exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zug, he showed 150 camera journeys on individual video monitors as a large global web. The Handrails are films that originally followed the world’s railings, pipes, and rims. A subproject of his complete handrail portrait of Venice shows fastpaced journeys along the edges of boats travelling through the city’s canals. The videos’ endless motion leads to a loss of orientation while also clearly orienting us along the (central) perspective.