Twin, Gabriel Else

Else Gabriel, born 1962 in Halberstadt, Germany

Ulf Wrede, born 1968 in Potsdam, Germany, both live in Berlin The 1960s are known for introducing “individual mythology” to the art world—the term used by the curator of Kassel’s documenta 5 in 1972 to refer to the artistic movement focused on the individual, often private experiences that shape the artist’s world. This approach was a radical change from the modernist understanding of art in the 1960s, which had repressed the private sphere in favour of sublime thought, as demonstrated by the American abstract impressionists.

Today, it is quite common for artists to incorporate these elements into their work. From the very beginning, it was mainly female artists who followed this movement, because it allowed them to distance themselves from the artistic tendencies that were then dominated by men and because it gave them the opportunity to search for and then define their identity as female artists.

Else Gabriel is an artist who involves the whole family in her creative project Else Twin Gabriel: her musician husband Ulf Wrede has been working with her since 1991, and even her two children, Linus and Greta, were gradually involved in her art. Perhaps as a parody on the heroic creations by ostentatious American painters, Gabriel used her little daughter in 2007 as a brush in her performance Kind als Pinsel (Kooperatorka)—Child as a Brush (Collaborator). She also staged the “Holy Family” and “Flight out of Egypt” with her children. In 2006, Gabriel went to the Berlin labour office with her children and waited in a queue like ordinary unemployed people. She documented this “waiting” with photographs. “It is partially performed, but we also actually joined in with the people,” Gabriel explains about her series of photographs from the world of the unemployed, who are not often the subject of art.

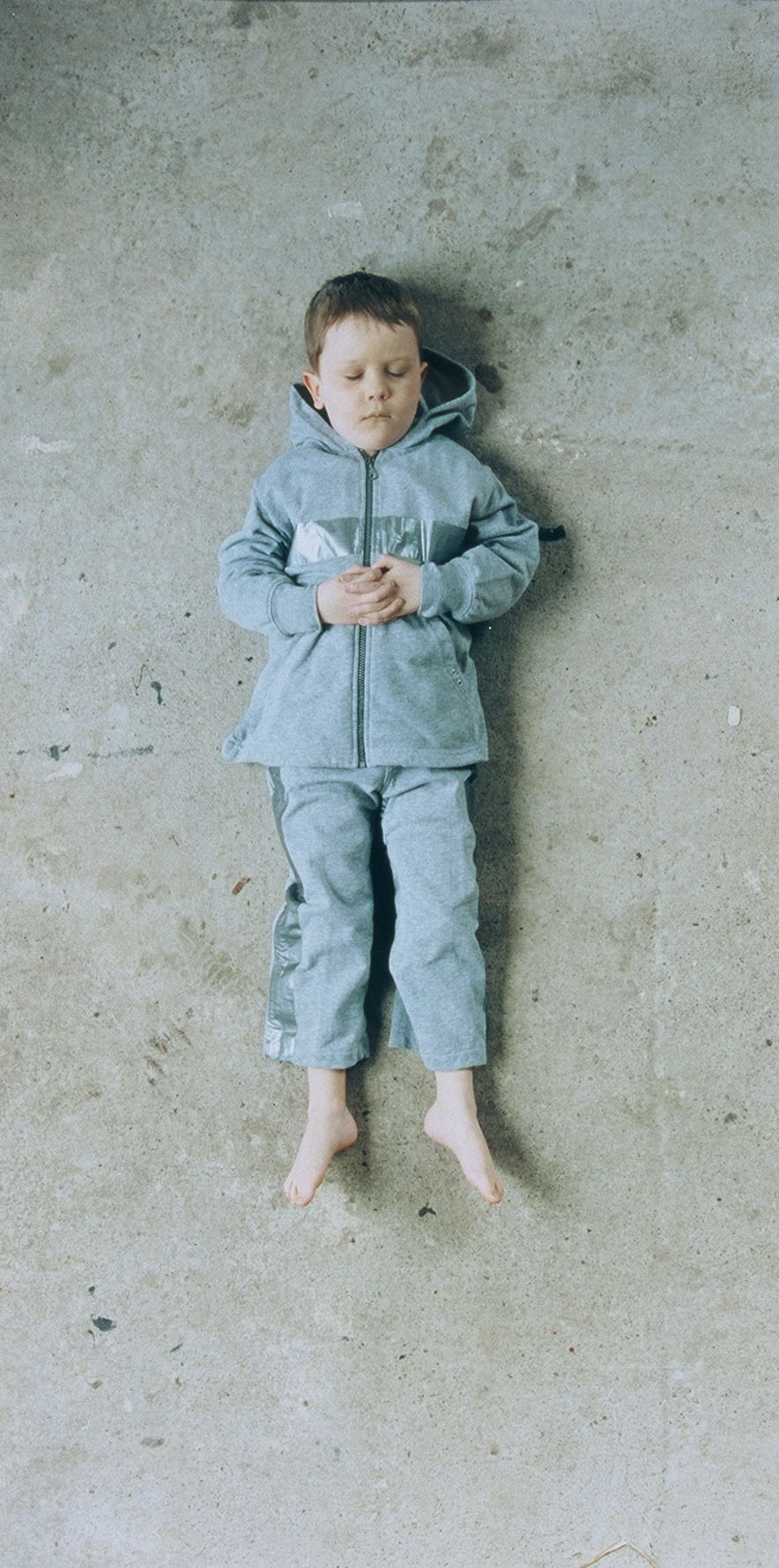

This author is also capable of provoking reactions, as in her series Die tote Familie (The Dead Family) from 2004: the images of a dead family make a conscious reference to the suicide of the Goebbels family, as well as to the dead terrorists from RAF, as illustrated by Gerhard Richter according to police photographs. Death, which was present in art for hundreds of years—if we think of the crucifixion of Christ—is for the most part avoided in contemporary art. Why? As Gabriel explains, “Looking at death, even with dignity, always portrays something dreadful, something strangely sickening that people are immediately uncomfortable with.”