Geboren 1956 in Rumburk, Tschechische Republik, lebt in Prag

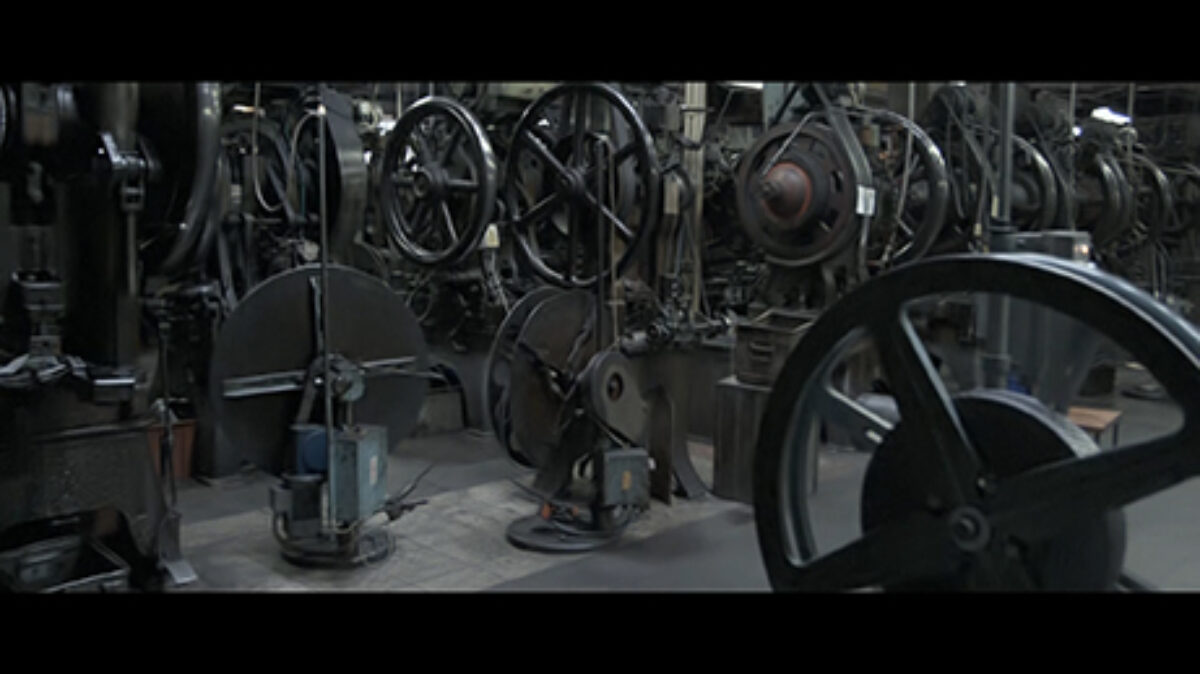

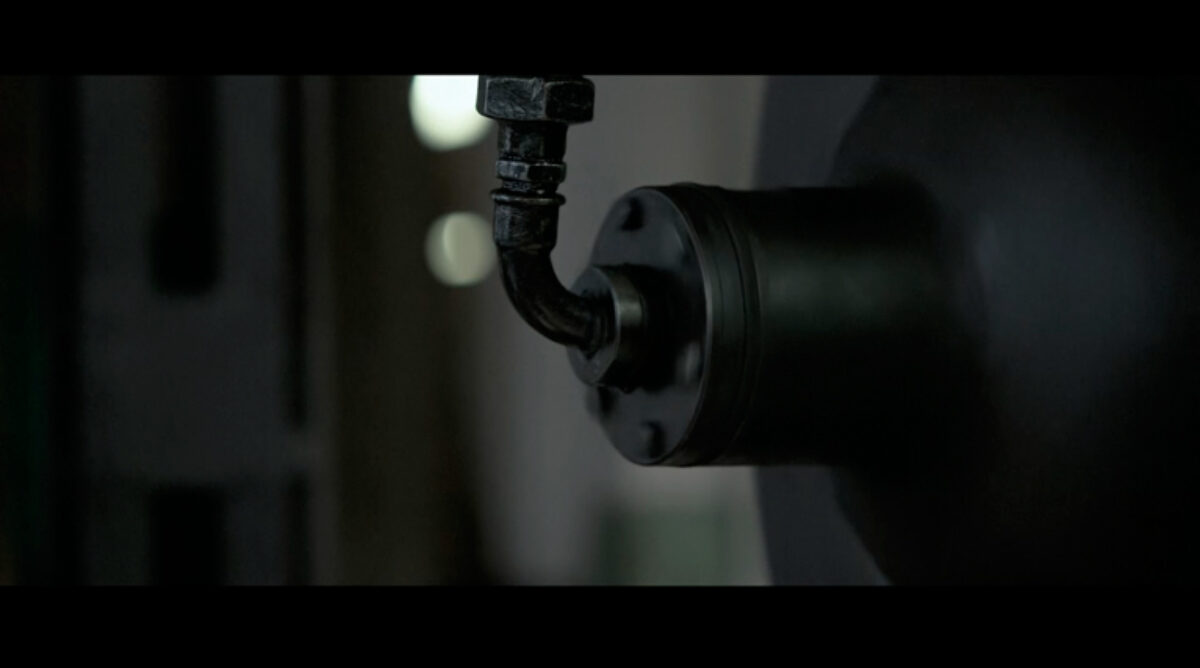

In den 1980er Jahren malte David auf eine heftige Weise und gründete die Künstlergruppe Tvrdohlaví (Hardheads). 2002 fotografierte er weinende Politiker und installierte ein blinkendes rotes Neonherz über der Prager Burg. Seitdem hat er abstrakte Bilder gemalt, sich selbst nackt auf einer Neujahrsgrußkarte fotografiert, eine verzerrte Statue „Revolution“ aus mehr als 80.000 Schlüsseln errichtet, weiter gemalt, mit seinen Artikeln und Erklärungen in den Medien für Aufsehen gesorgt und 2009 einen schönen Film über verlassene Maschinen in einer Koh-i-noor-Fabrik gedreht. Dies alles hat Jiří David getan. Er gehört zur Generation von Künstlern, deren Ambivalenz, Inkonsistenz und Missachtung jeglicher Kontinuität, Tendenz zur Provokation und sexuell gefärbten Skandalen, Theatralik, Medienbeteiligung und auch Faszination für Malerei Reaktionen auf die Wendepunkte der sozialen, politischen und kulturellen Entwicklungen der letzten Jahrzehnten sind.

Alle Konflikte und Paradoxien der Gegenwart, der Zusammenbruch moderner Fortschrittsvorstellungen, begleitet von der Kollision verschiedener Kulturen und Ethnien, und eskaliert durch das Internet, Gewalt, die durch mittelalterlichen Fundamentalismus motiviert ist, und der Einsatz neuester wissenschaftlicher Technologien haben dieser Generation die Freiheit eines „Hofnarren“ gegeben, der sich in die Tiefen des Antagonismus und der Irrsinnigkeit stürzt. Während diese Entdecker hin und wieder an die Oberfläche kommen, bringen sie eine Realität zutage, die die meisten Menschen lieber vergessen würden.

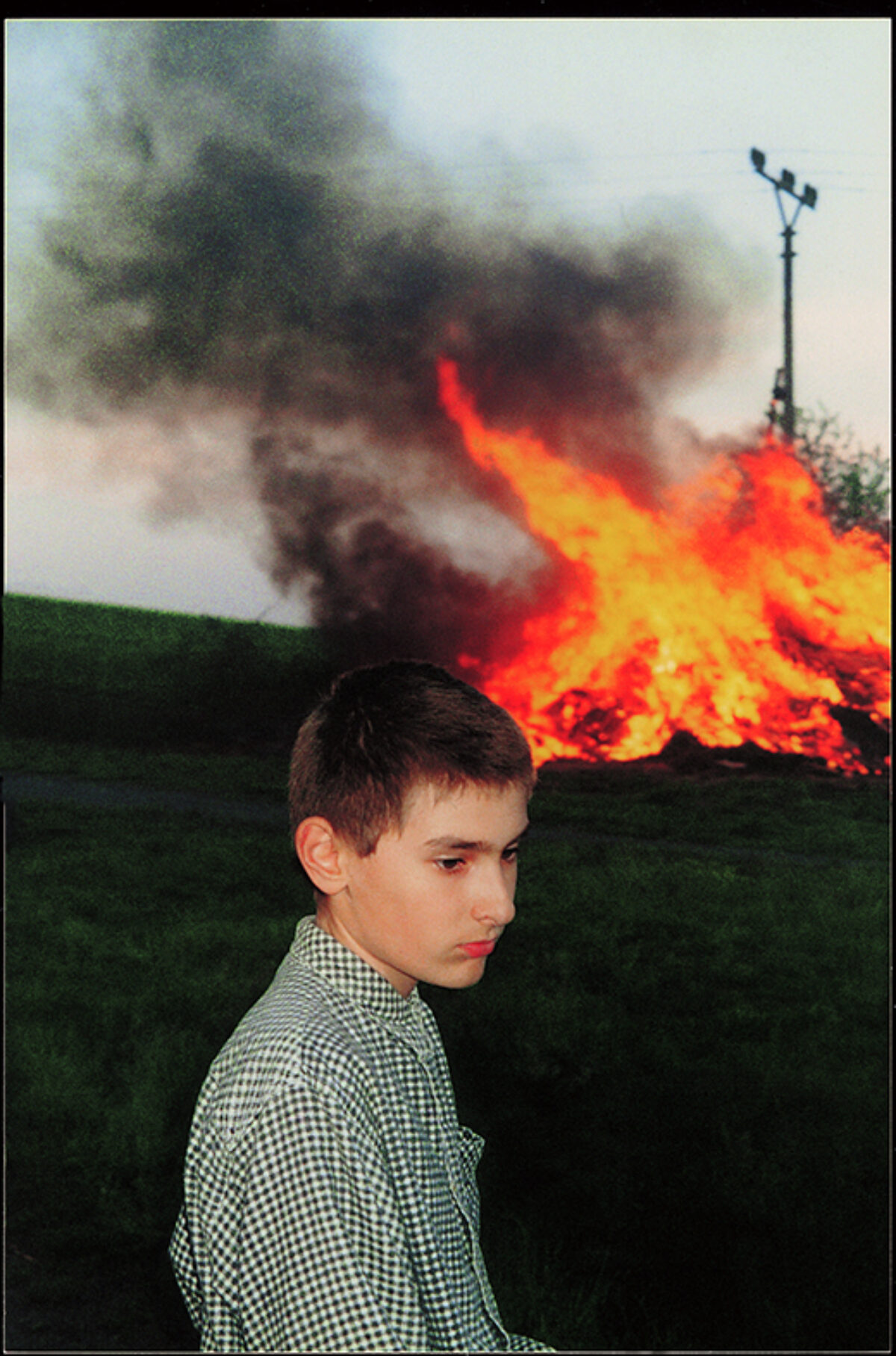

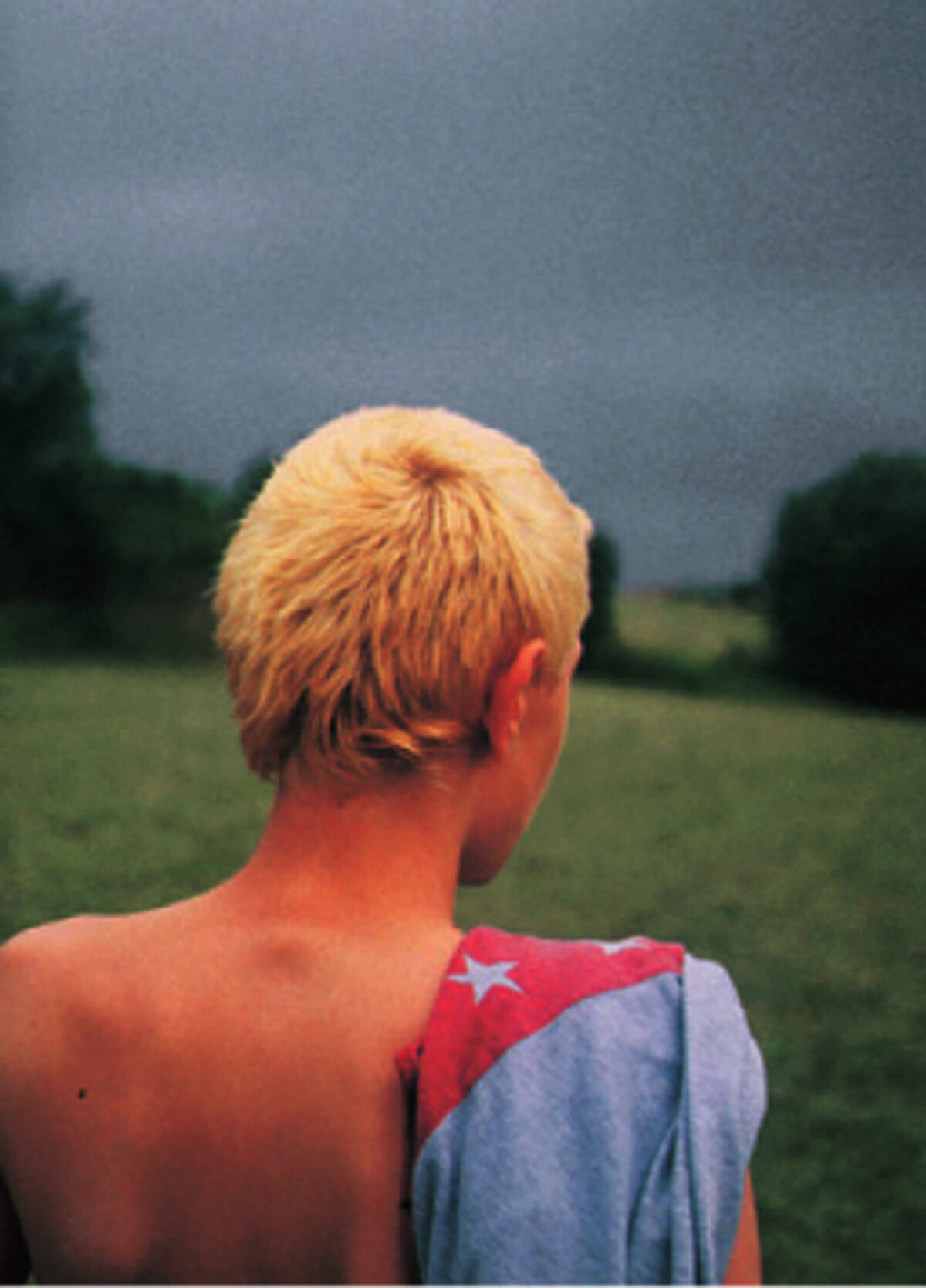

Eine dieser Unternehmungen ist Davids Fotoserie „My Hostages“ von 1998. Der Autor fotografiert seine beiden Kinder als Gefangene. Ihre Hände und Füße sind gefesselt, und sie sitzen in Kostümen auf Stühlen, umgeben von Kinderrequisiten. Auf den ersten Blick ist klar, was er zeigen will: nicht nur ein gesellschaftliches Tabu, nämlich den sexuellen Missbrauch von Kindern, sondern auch die gängigen Bilder von Geiseln in den Medien, wie sie von islamischen Terroristen der Welt präsentiert werden. Zweifellos ist dies eine flagrant provokante Darstellung, die Abscheu und Ekel erregt, aber auch Faszination. Wir können diese Bilder nicht aus unserem Kopf bekommen. Slavoj Žižek, ein Philosoph aus Ljubljana, sieht solche widersprüchlichen Beziehungen zu einem Kunstwerk und zur Welt im Allgemeinen als typisch für den Postmodernismus: „Wir treten in den Postmodernismus ein, wenn unser Verhältnis zu Dingen antagonistisch wird. Wir geben uns in gewisser Weise diesen Dingen hin. Sie ekeln uns an, aber gleichzeitig sind wir von ihnen angezogen.“ Und genau das passiert im Werk von Jiří David, einem Künstler mit vielen Gesichtern.

Text von Noemi Smolik