Kintera, Kristof

Born 1973 in Prague, Czech Republic, lives in Prague

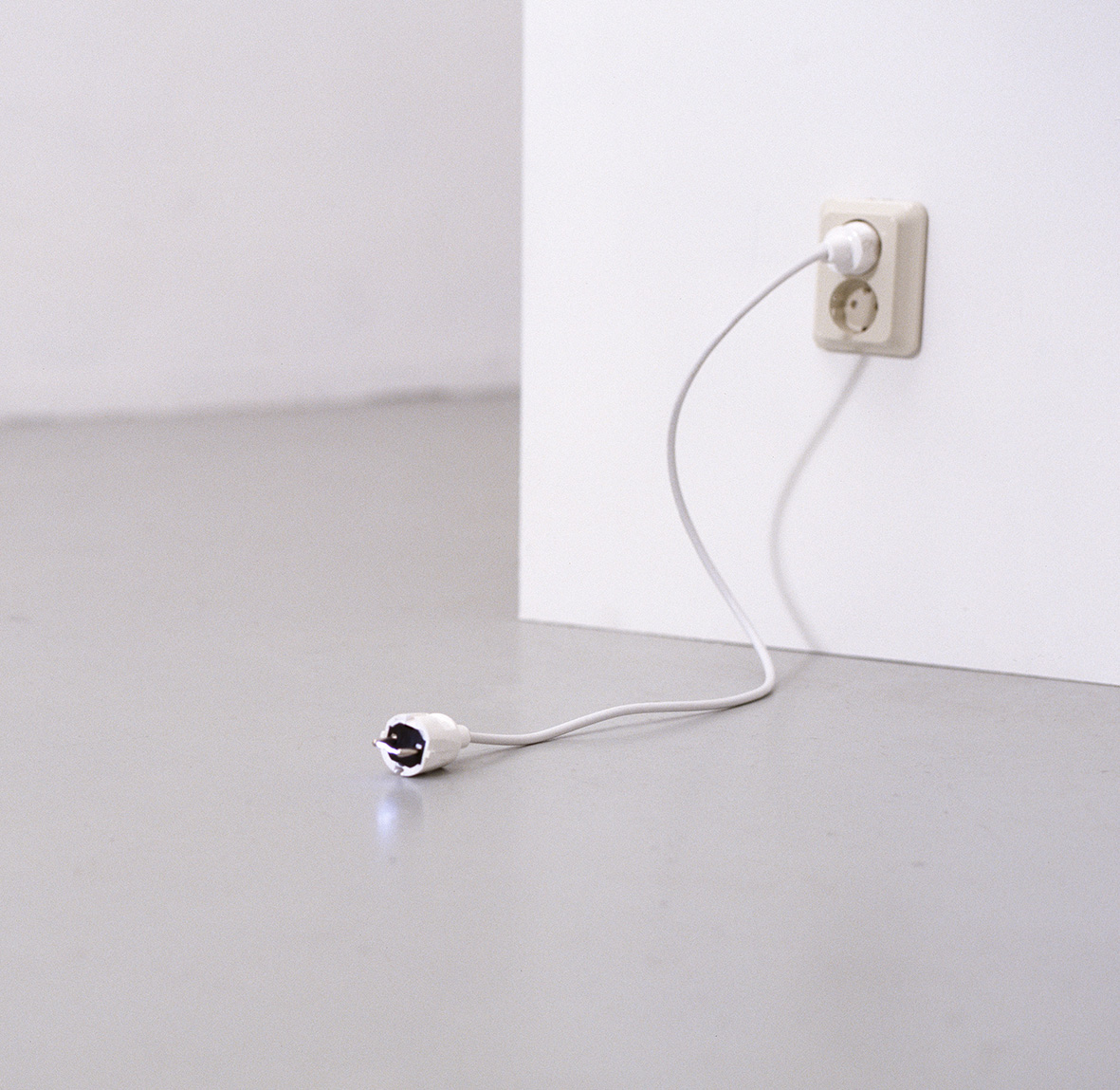

His objects speak, light up, move around, and emit smoke, and yet they are not children’s toys. They do, however, have a lot in common with childhood, or rather puberty. They show the same impertinence and willingness to provoke as young people when they first realize that the world is not as just and peaceful as what they thought as children. Kintera’s world is filled with protest and revolt. “I am sick of it all,” reiterates a 2003 shopping bag from the series Speaking.

While protest, revolt and non-conformity disappear in the everyday lives of adults, thankfully, these often remain in art. The Californian artist Mike Kelly is one of these artists who has successfully integrated the world of children and adults into his art. And similar to Kelly, Kintera also sees the adult world not only as full of anxiety, horrible images and consumerism, but as full of absurd phenomena. In Kintera’s world, household appliances mutate into amorphous shapes charged with electricity, and thanks to built-in vibrators, they even occasionally rattle and shake. From 1997 to 1998, this artist produced 26 different kinds and even provided them with boxes and silk wrapping paper carrying logos of firms with such lustrous names as “Ultron” or “Utitool”. However, selling these was more of a problem: there were only a few shops that were willing to place his “appliances” in their shop windows, or for that matter, directly on the shelves.

Kintera’s deformed and non-functional bicycles are also known, as well as pillar sculptures made of pillows or bags of cement, which can be seen as a parody on the famous Endless Column by Constantin Brancusi, an icon of modern sculpture. This vertical tower of bags from 2007 is entitled Do it Yourself (After Brancusi). And even the iron barrel from 2008, entitled Holy Spirit Opened, which lets off steam, is banged up by the disrespectful comment on the metaphysical flights of modernism.

The small figure dressed in jeans and a coloured shirt that is banging its head against the wall until the plaster falls off is entertaining in a tragicomic way, bordering on atrocious. This is called Revolution, and as Kintera says himself, it is a sarcastic commentary on all eternally revolutionary, though always pointless, attempts to tear down a wall. An ancient, pre-revolutionary proverb says “You cannot break down a wall with your head”. And this is a key message for Kintera’s work: behind such banal scenes are hidden unpleasant truths.