Born 1940 in Tokyo, Japan

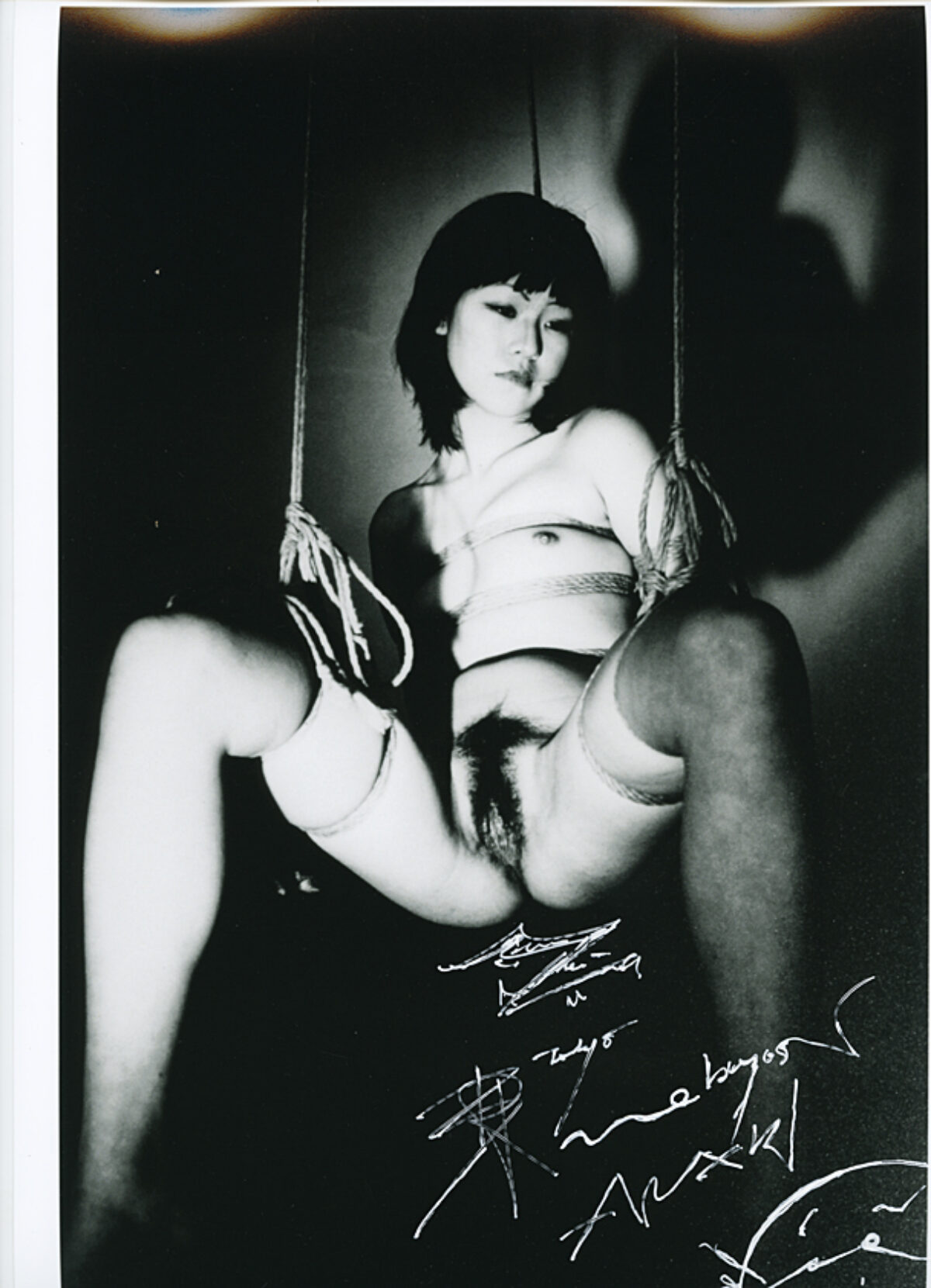

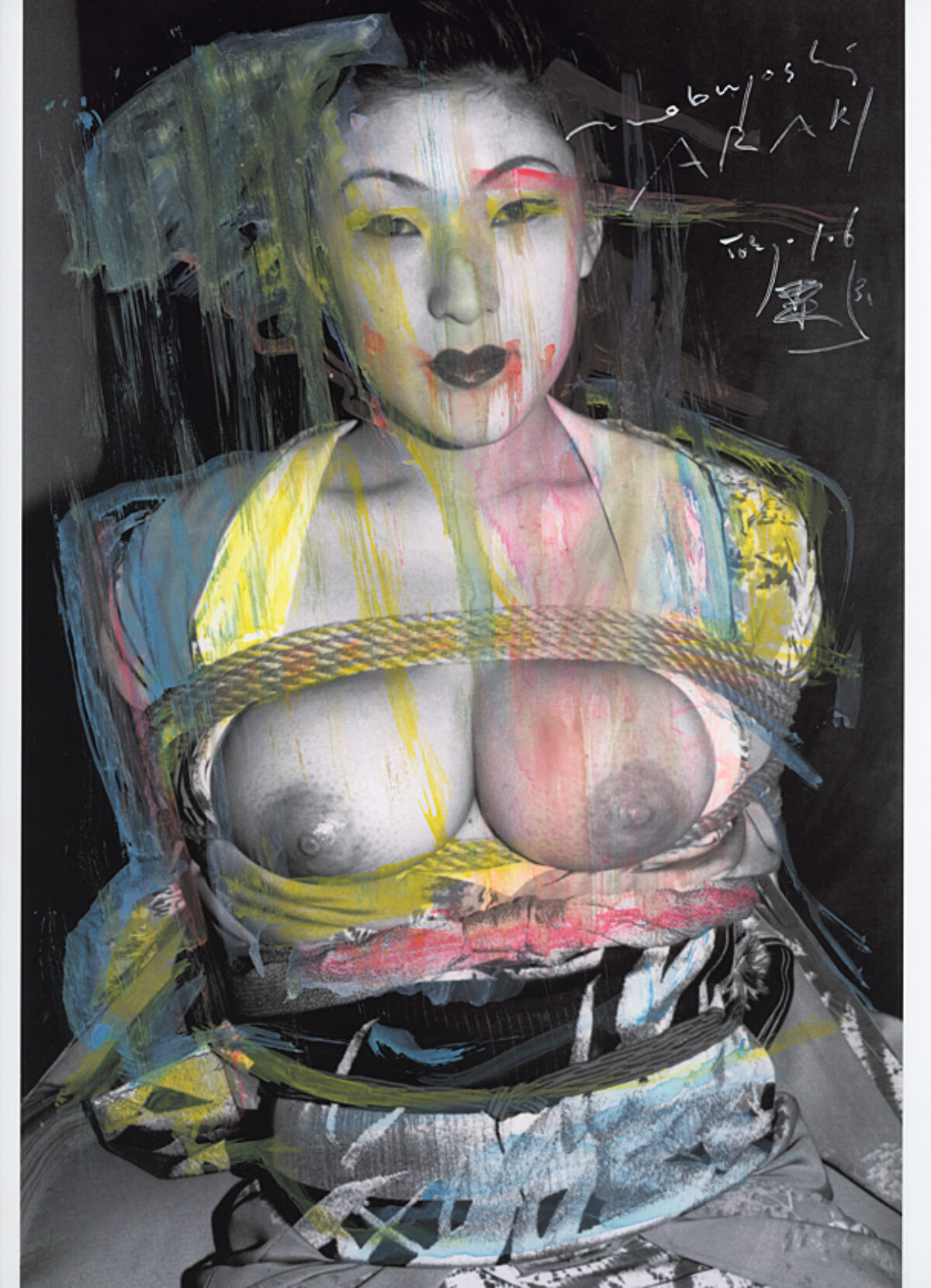

Whether he captures women naked, half-naked, lying on the sofa so that it is possible to see their belly, bound or fully clothed, whether he is showing mature women or innocent-looking girls, Nobuyoshi Araki’s photographs are always sexy. Influenced by French photographers Brassai and Henri Cartier-Bresson, and by the films of Jean-Luc Godard, in 1964, the artist, began to photograph children. It was his photographic series, later named „Sentimental Journey,“ which made him famous. In this series, he documented his own honeymoon, full of sexual desire and fantasies.

The success of „Sentimental Journey“ encouraged Araki to continue his exploration of sexual themes. His goal is to smash all of the taboos associated with sex and sexuality. In Japan, Araki’s work is not always accepted enthusiastically. His books are censored and attacked by the press. However, these controversies have only helped Araki become one of the most famous artists in his country. Today, his books sell briskly, yet his fame is not only based on scandals and pornography, as his detractors claim. The position from which Araki captures his female subjects is that of a man in the moment of sexual desire – a moment in which there is a need to appropriate the desired object. This is exactly what his photographs make extraordinararily visible.

In interviews Araki compares photography to the sexual act: “When we succumb to the impulse to pull out the camera and aim the lens at an object, we are being driven by the need to appropriate that object. In the moment when you take the picture, you feel that you have successfully captured the object of your desire, but, ultimately, you will hold nothing more than a picture.”

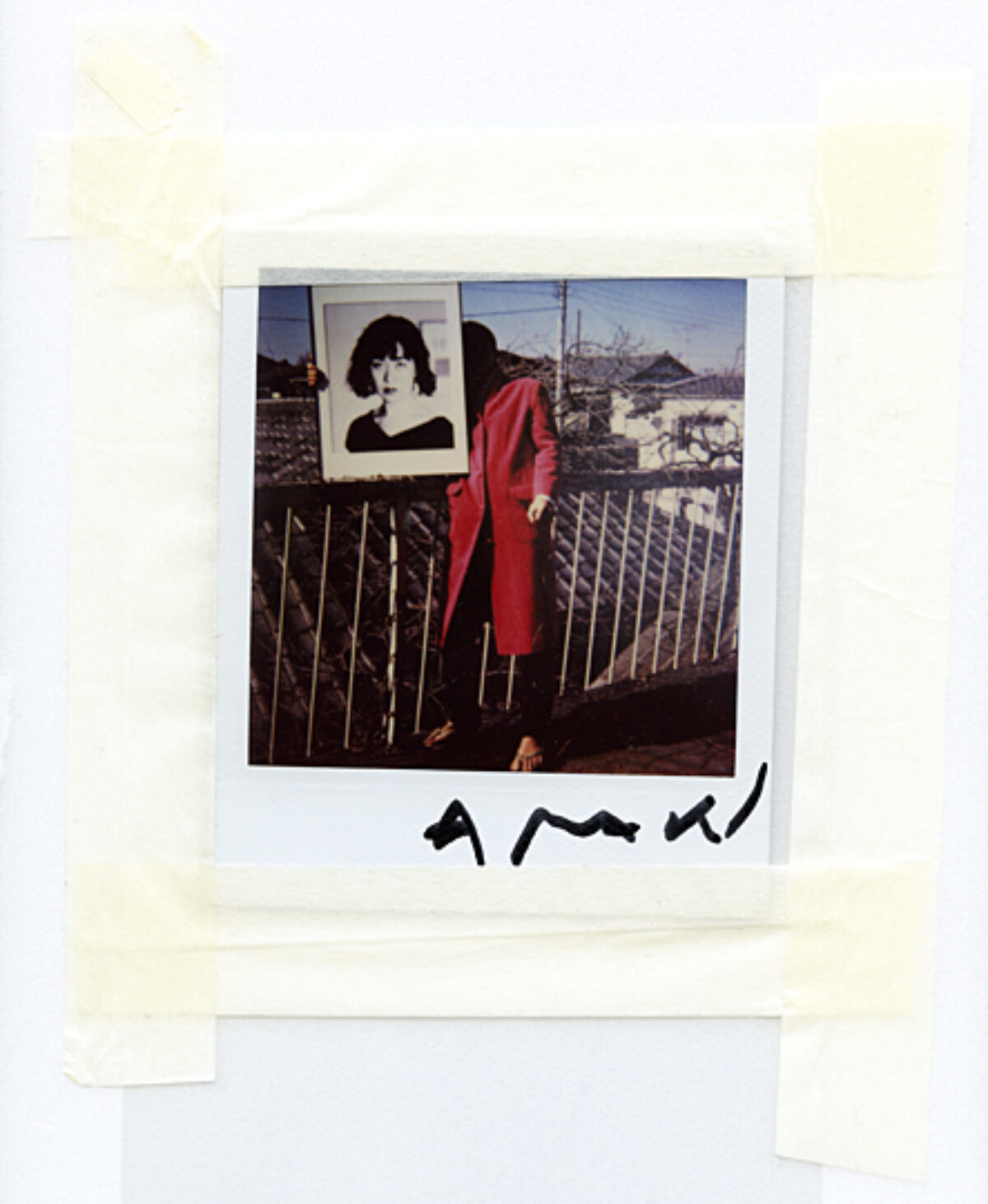

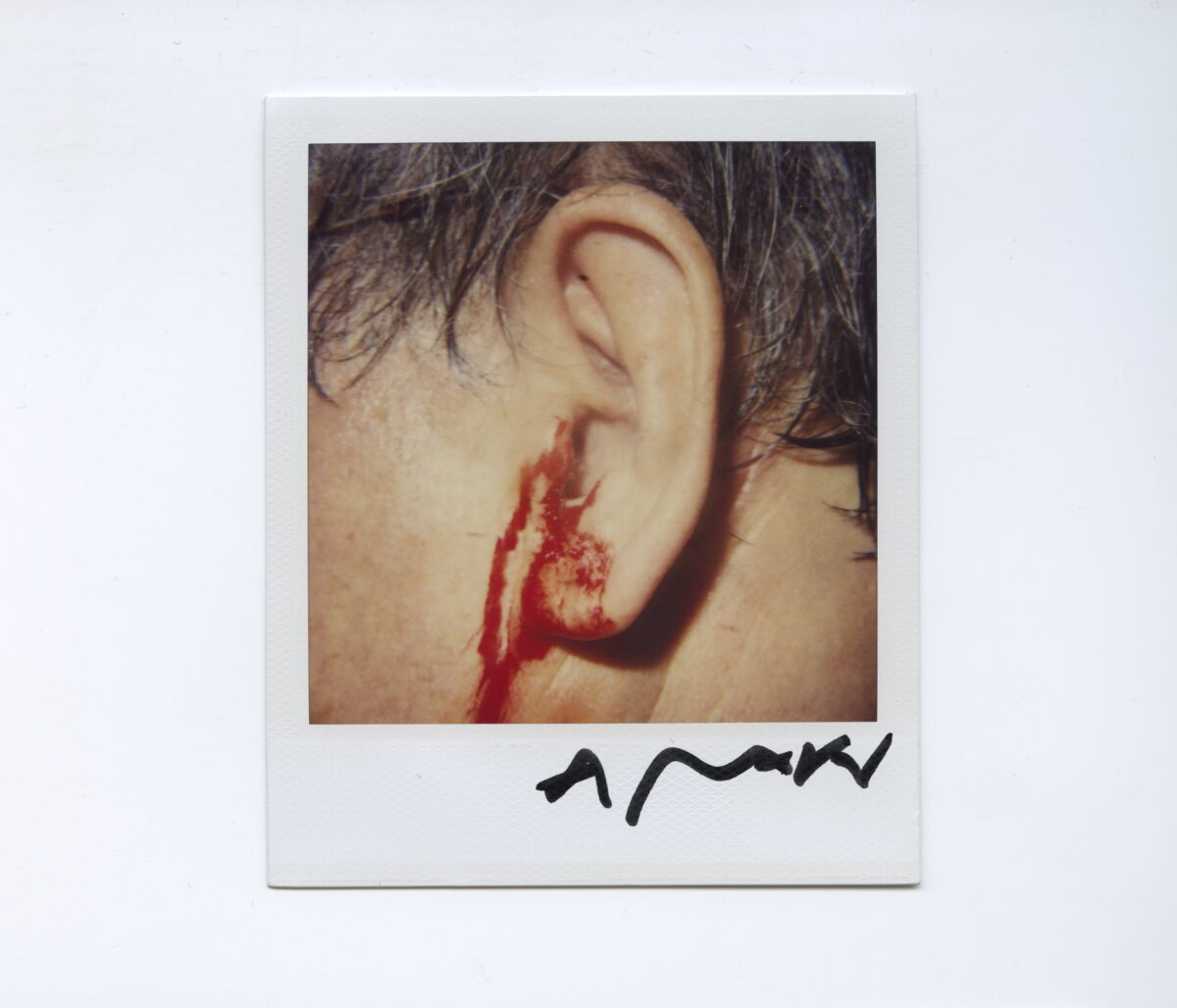

Every act of taking a photograph is not only full of sexual desire but is also full of the desire to stop time. It is as if taking a photograph simulates the sexual climax – a moment in which time is overwhelmed [defeated, perhaps?] and [seems to cease to exist], a moment that resembles death, [when time is stopped forever]. Since the death of his own wife, which this tireless photographer documented, all of Araki’s photographs serve as his speechless witness of death. They are provocative! It is Araki‘s obsession with death, not with sexuality, that is the source of the subversive quality of his pictures. Today, perhaps it is death that is taboo, and Araki, who once said that every photographer is a murderer, knows this well.

Text by Noemi Smolik