Born 1966 in Reinbek, Germany, lives in Berlin.

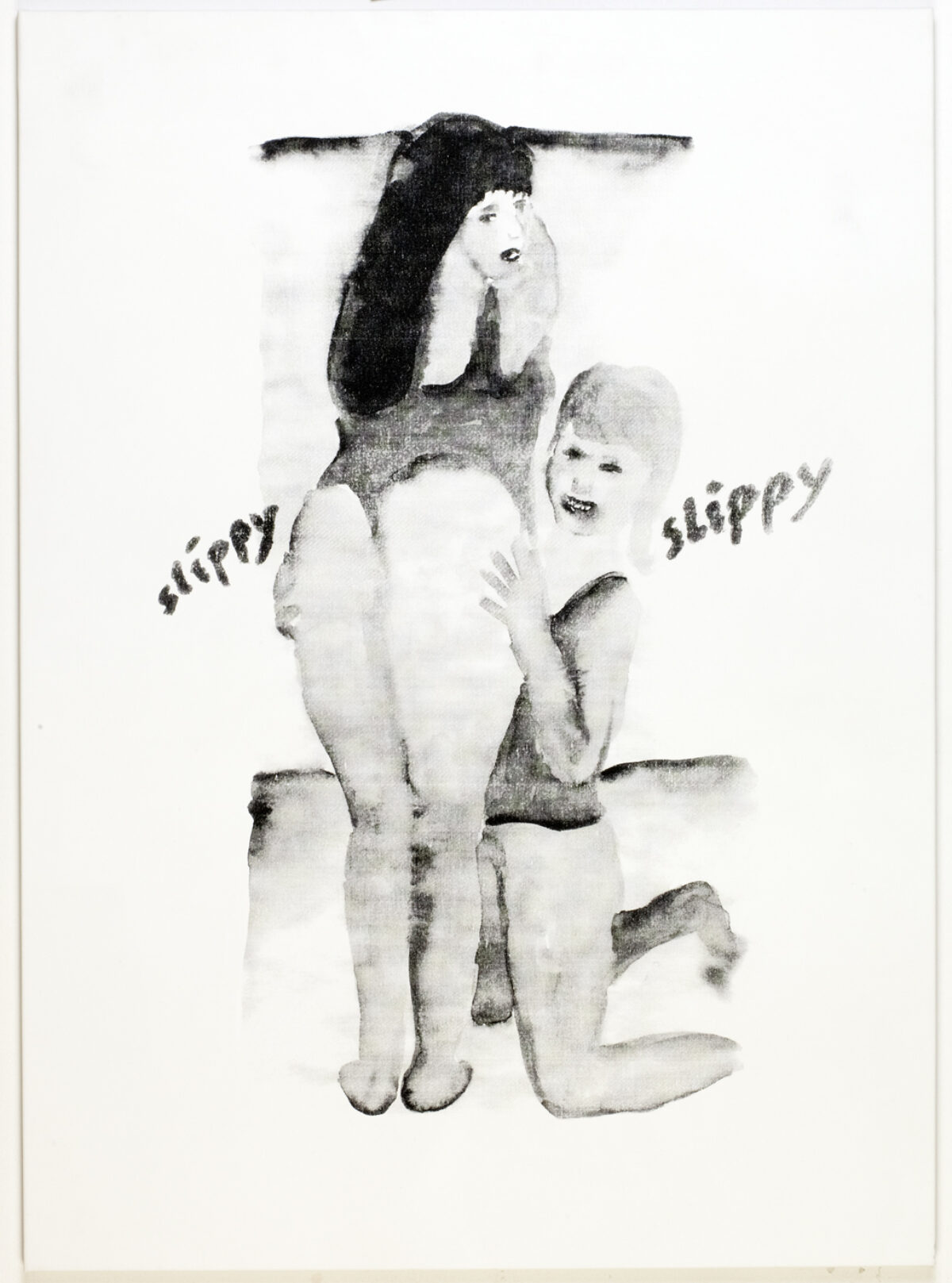

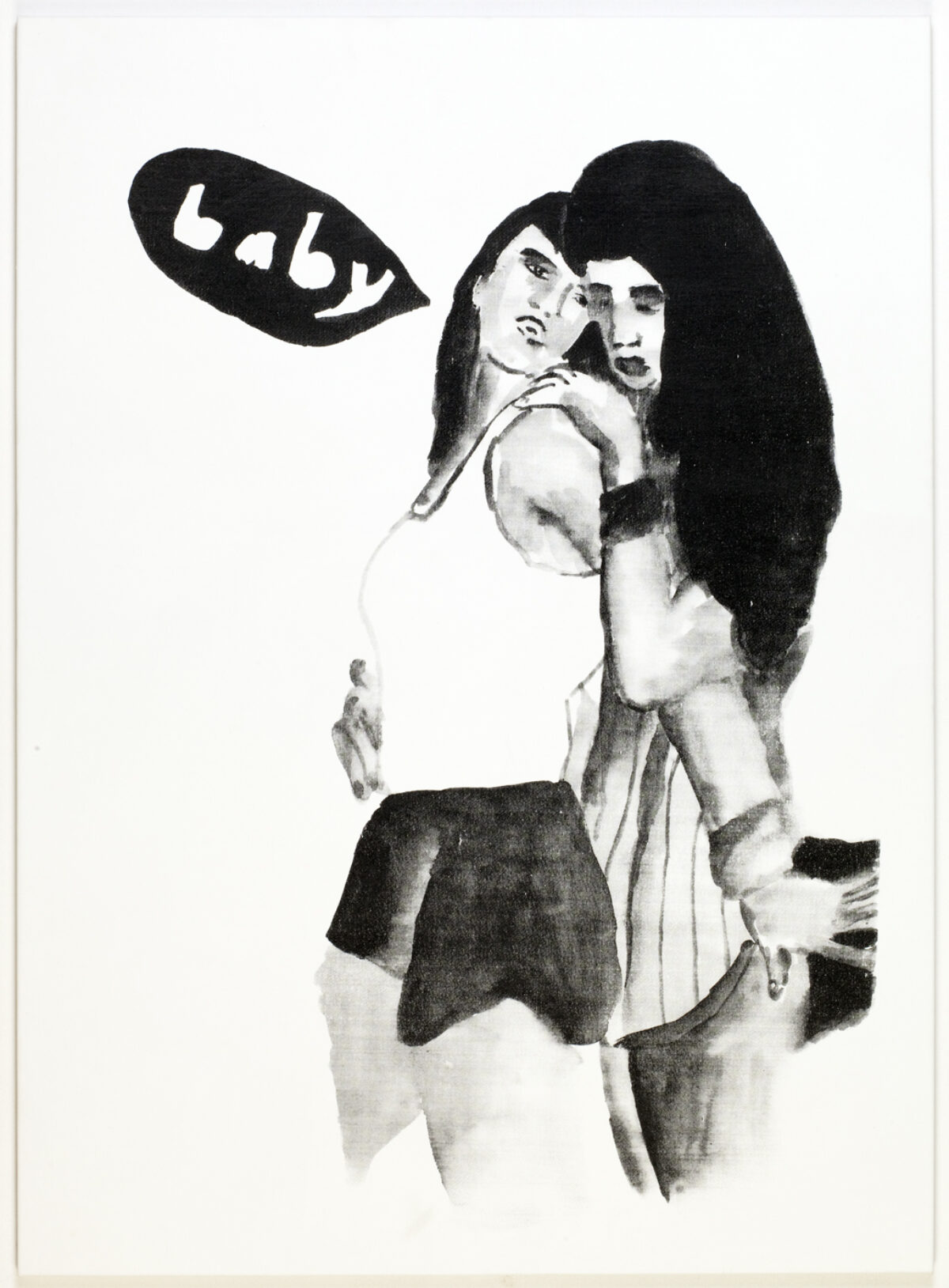

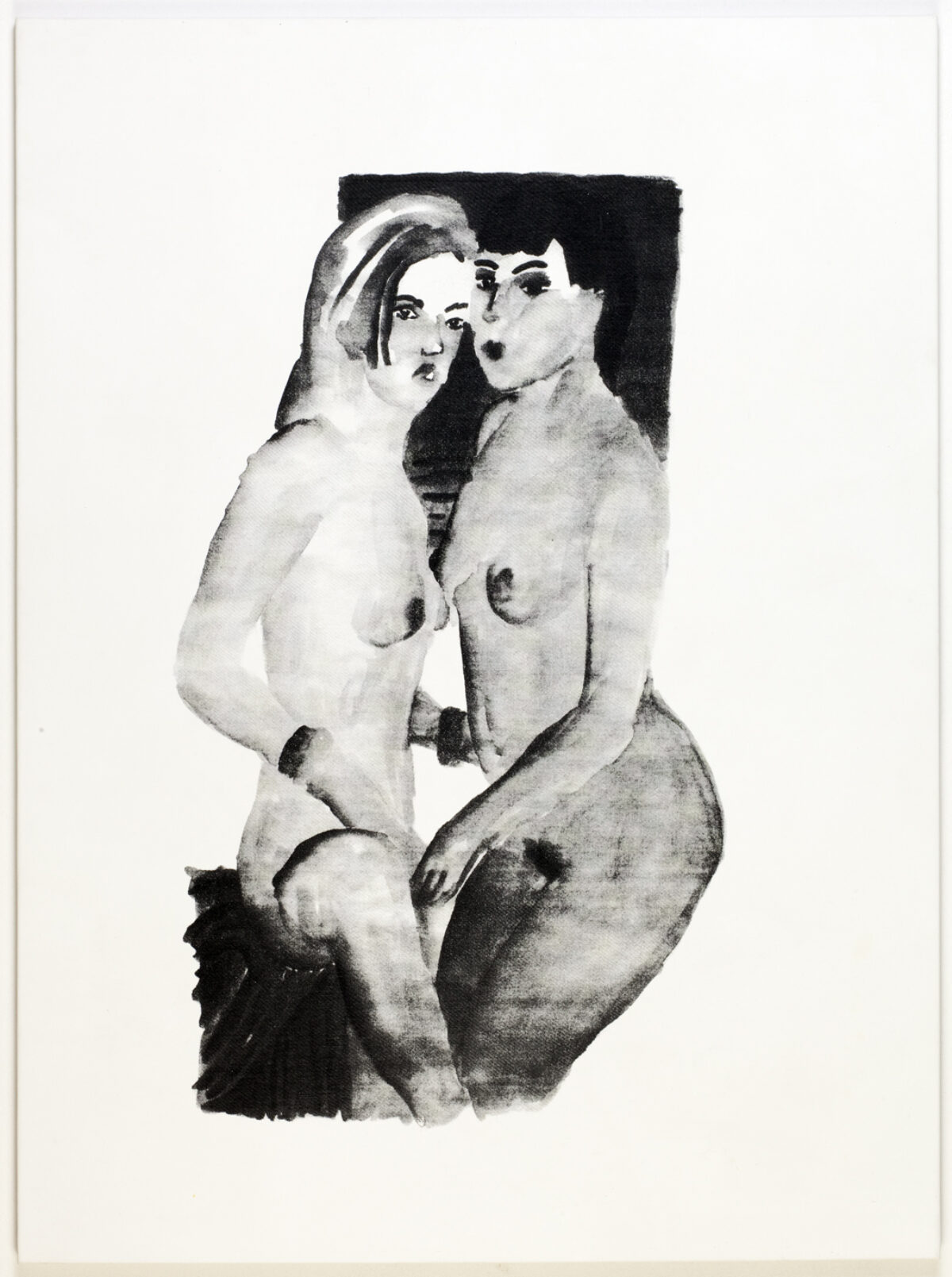

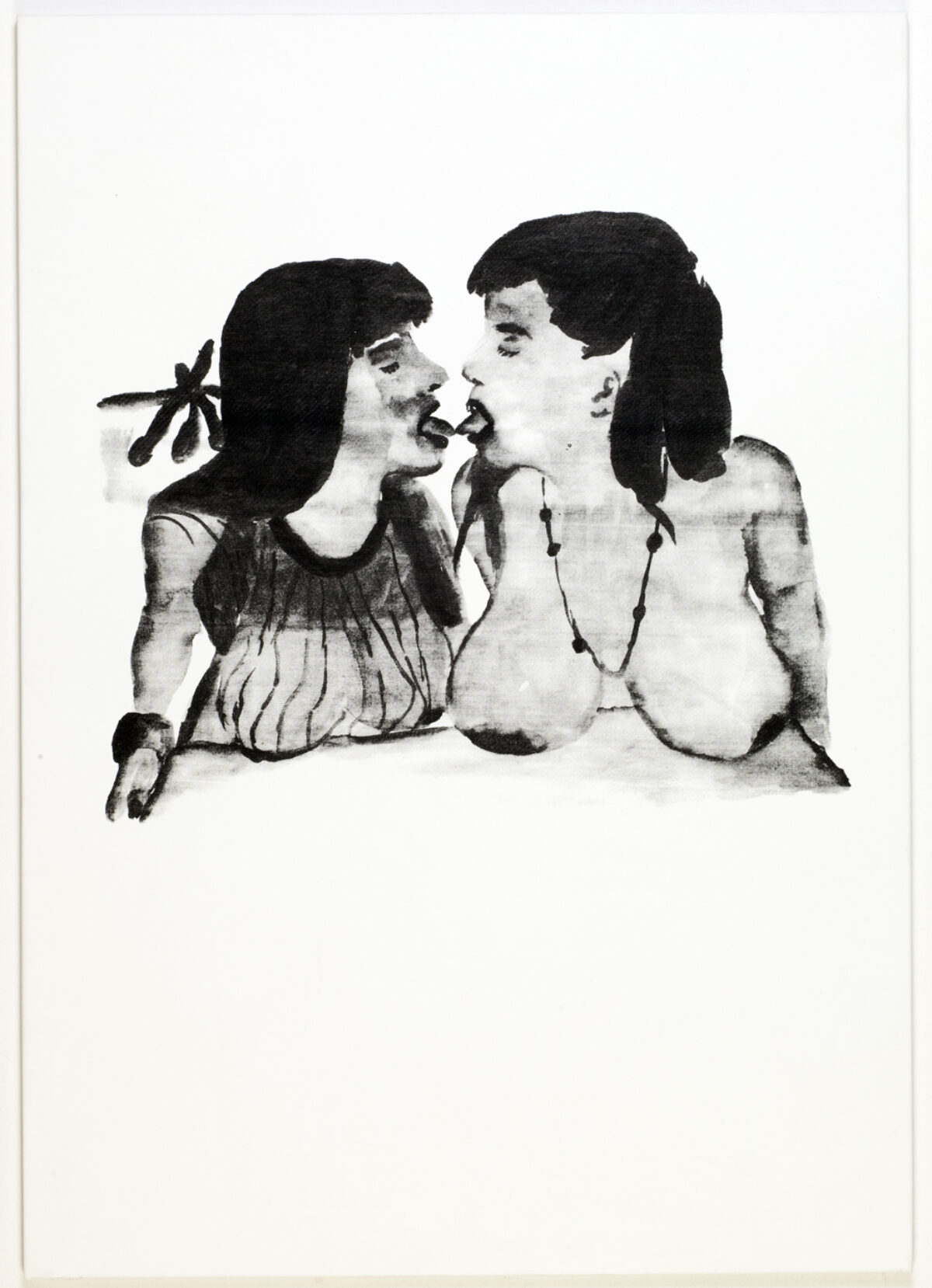

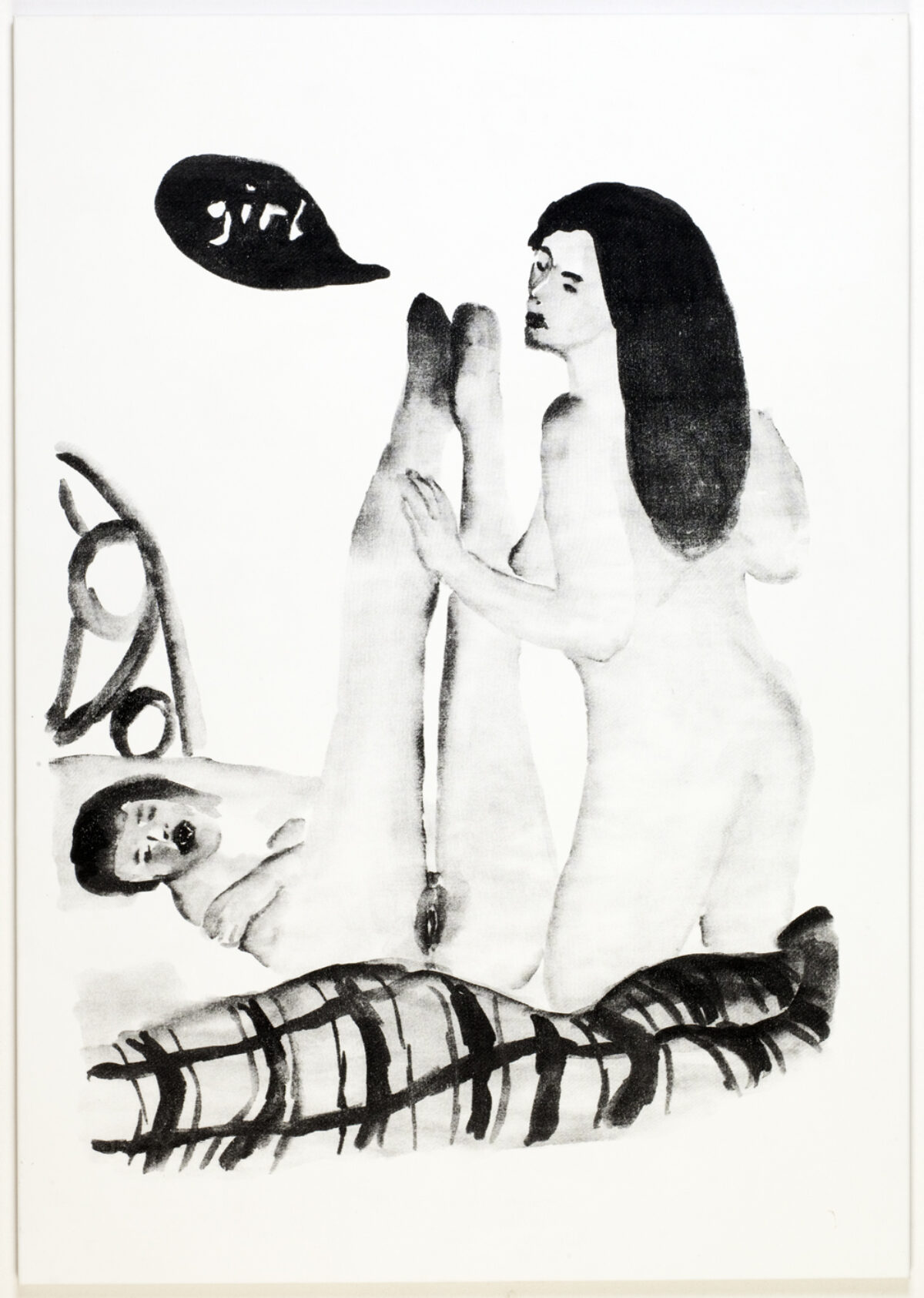

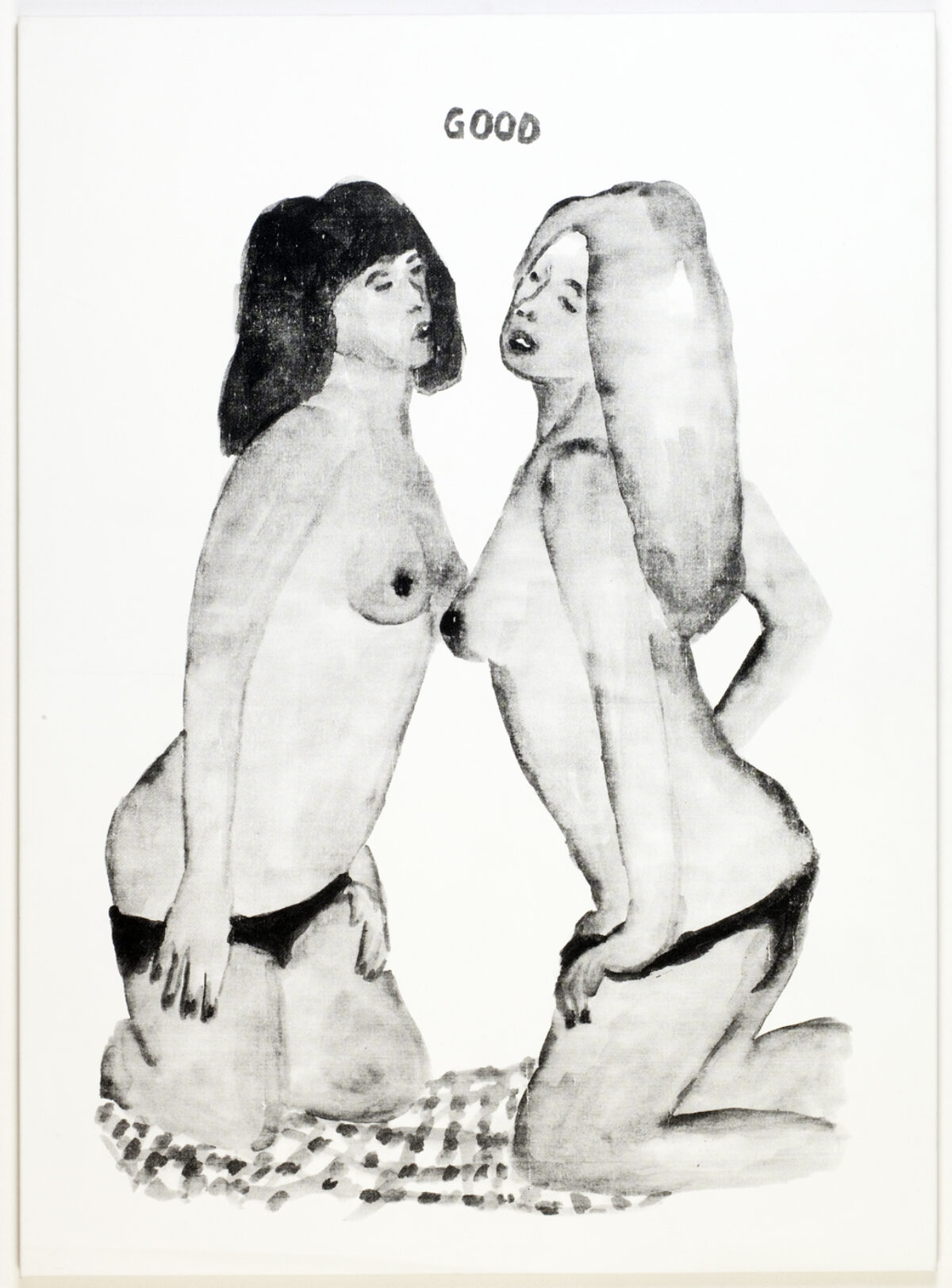

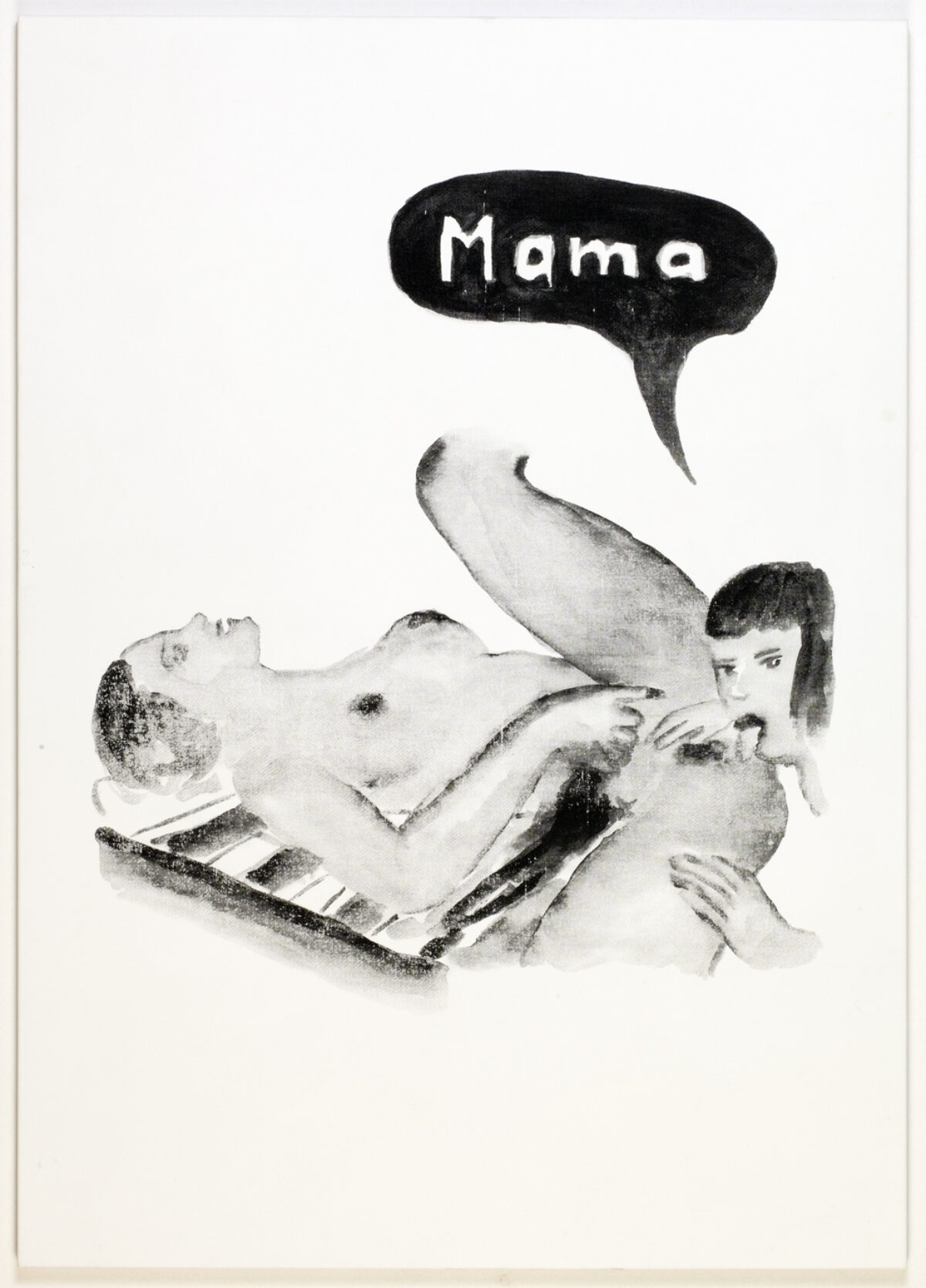

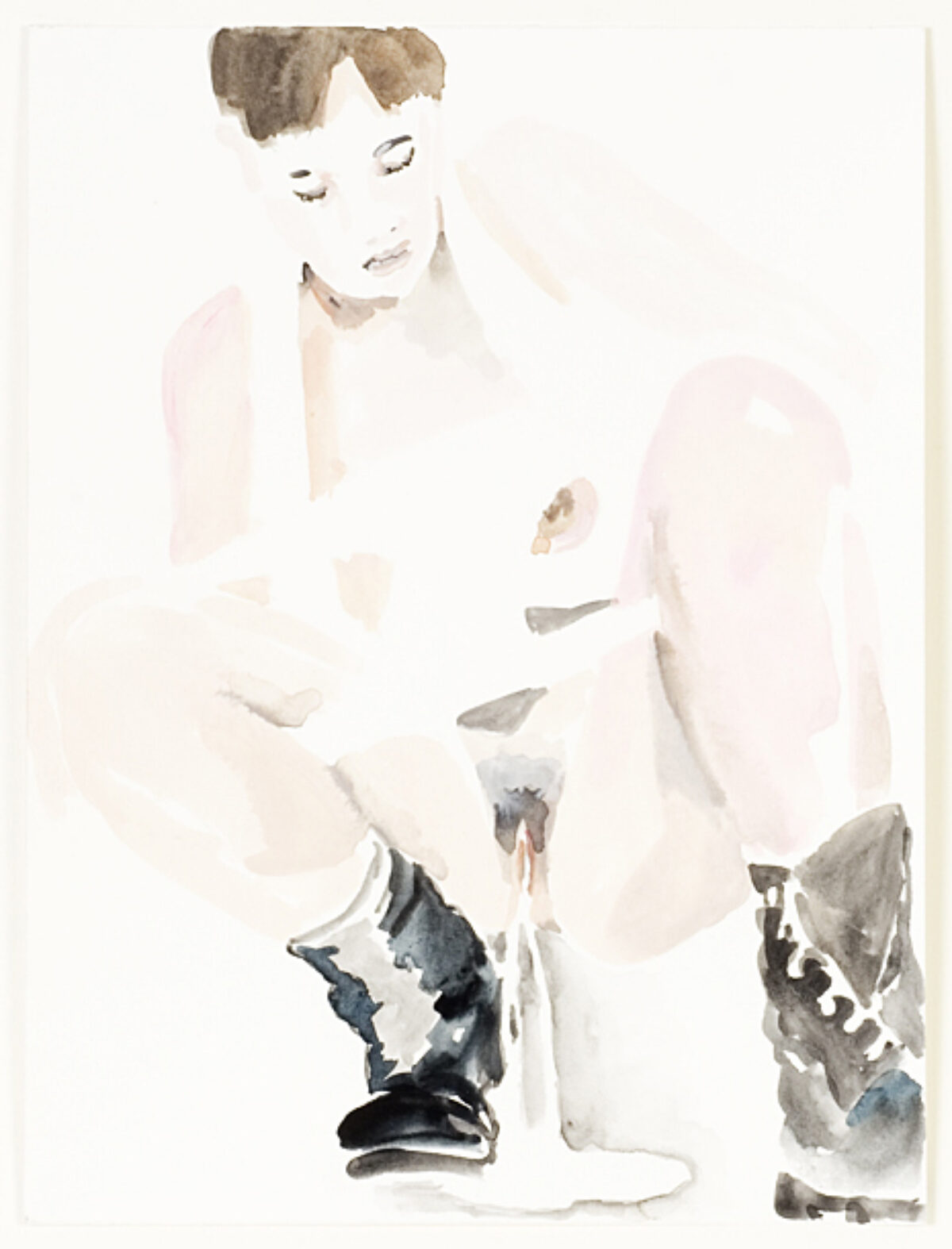

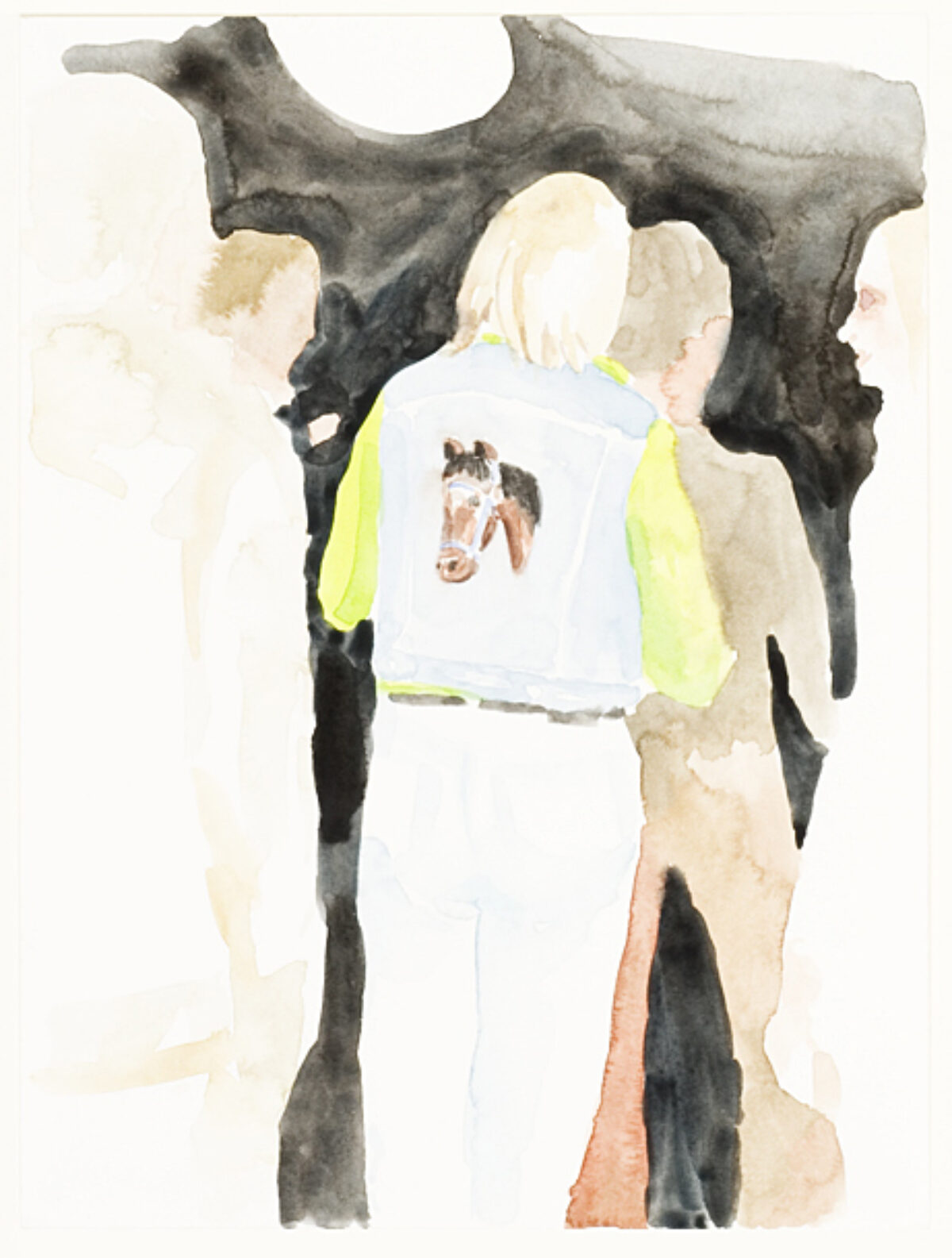

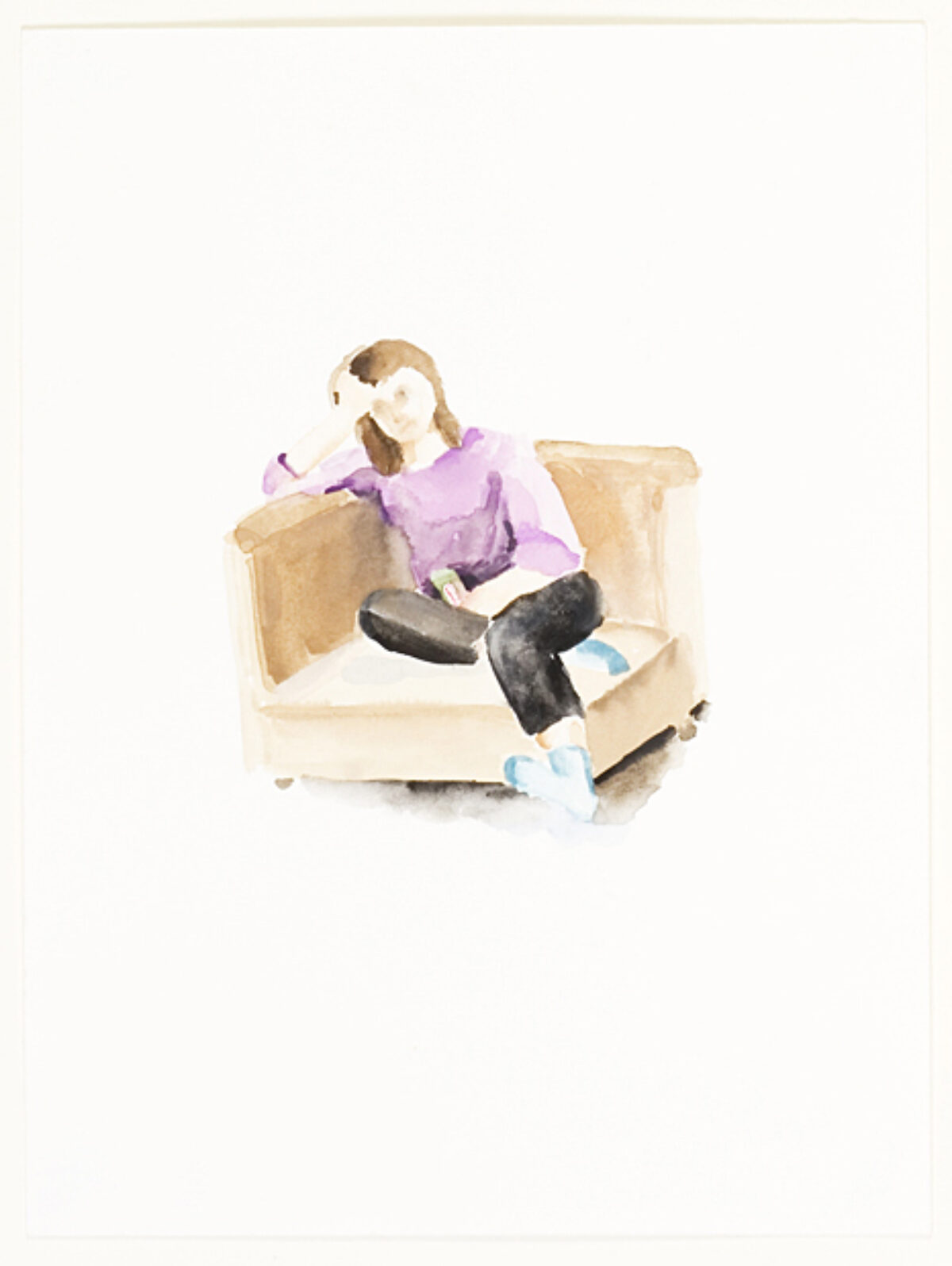

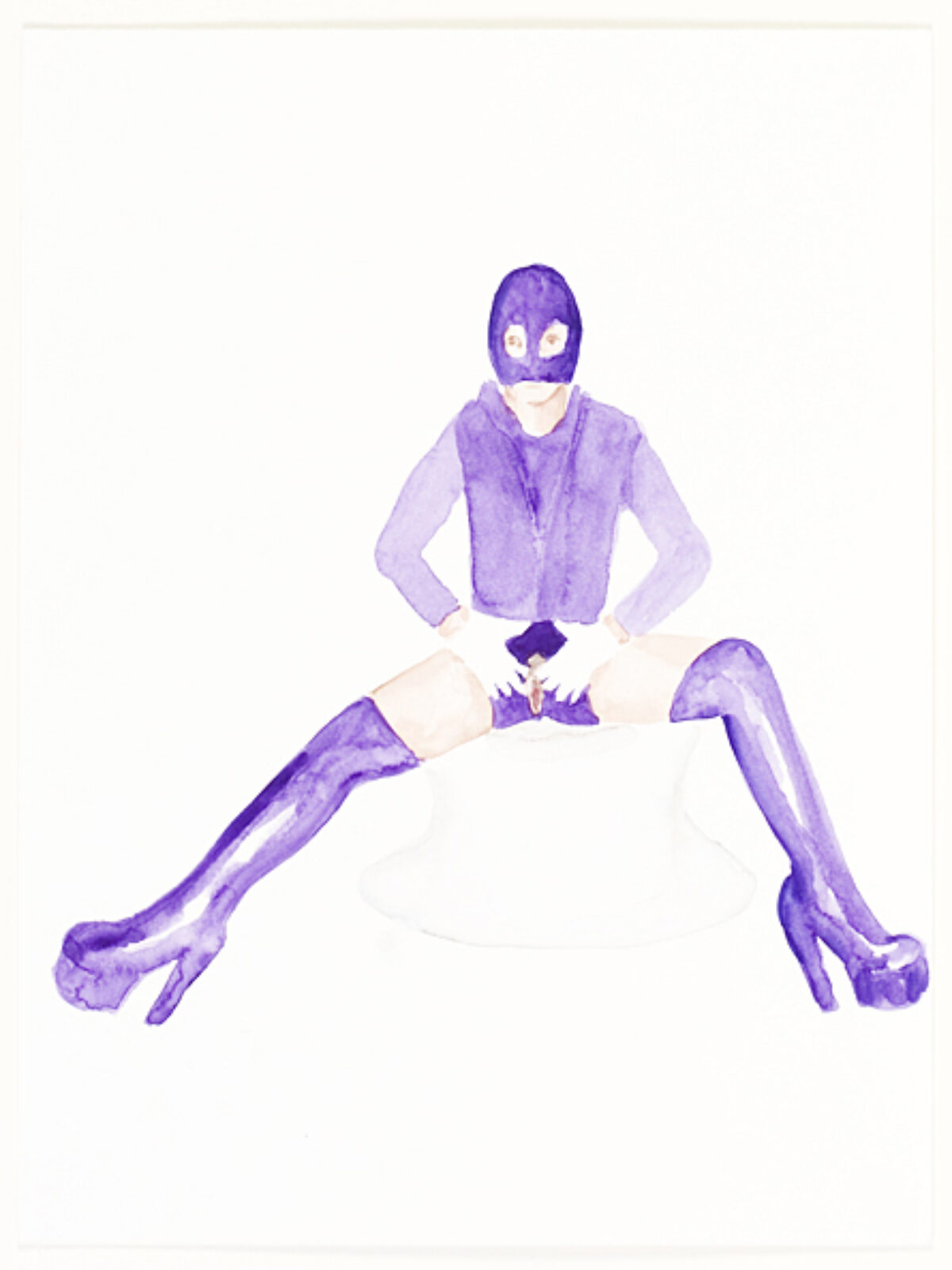

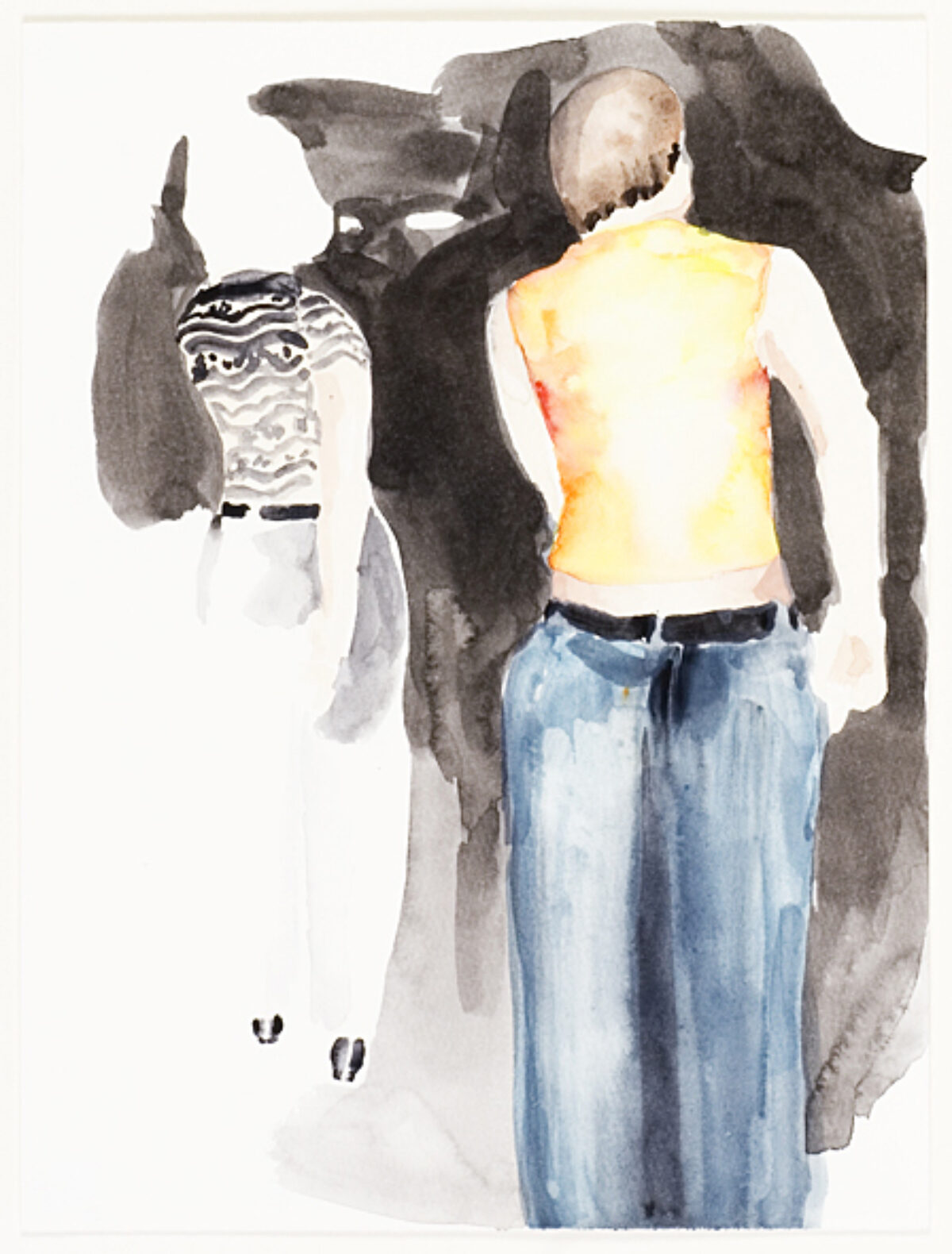

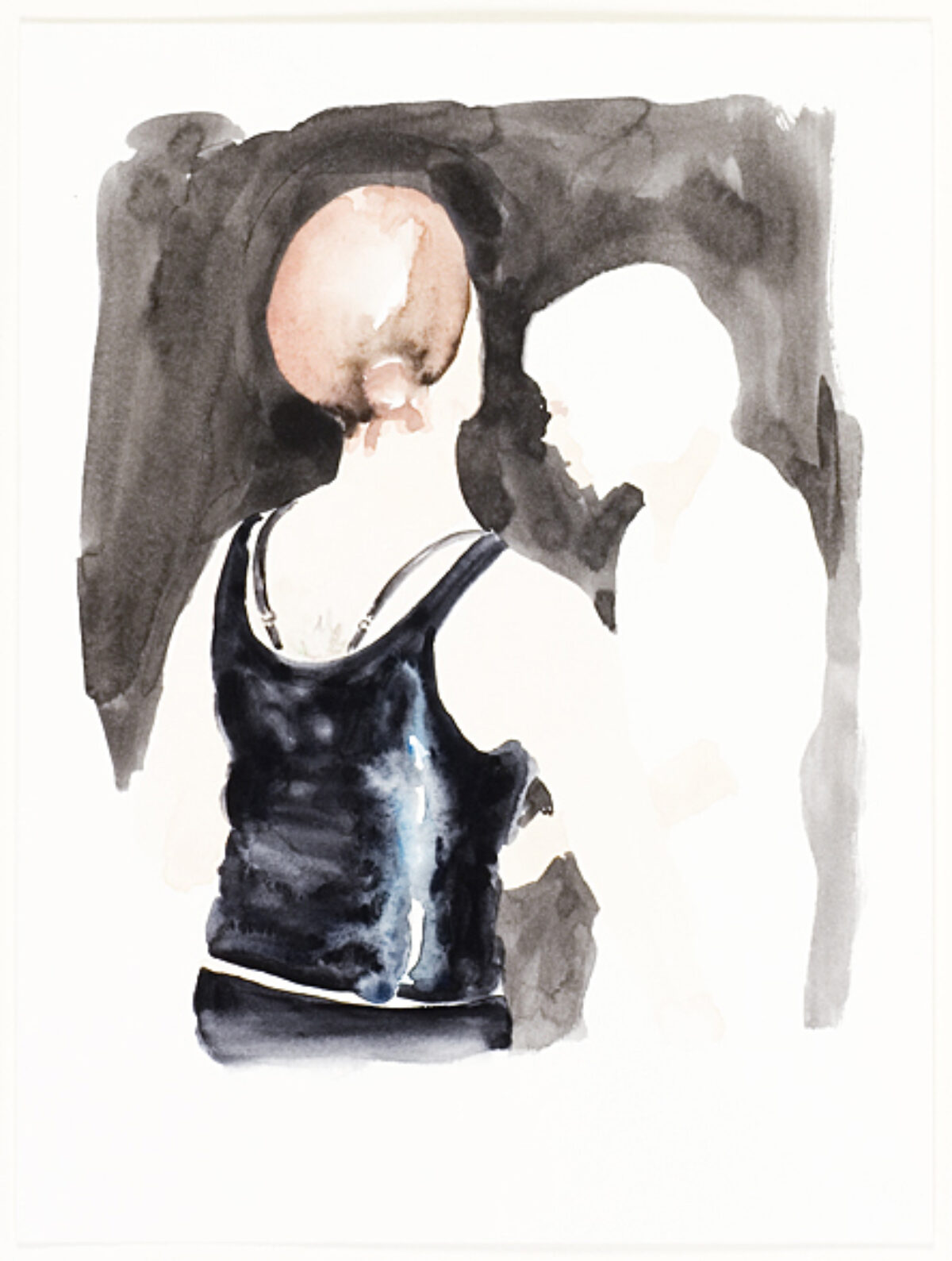

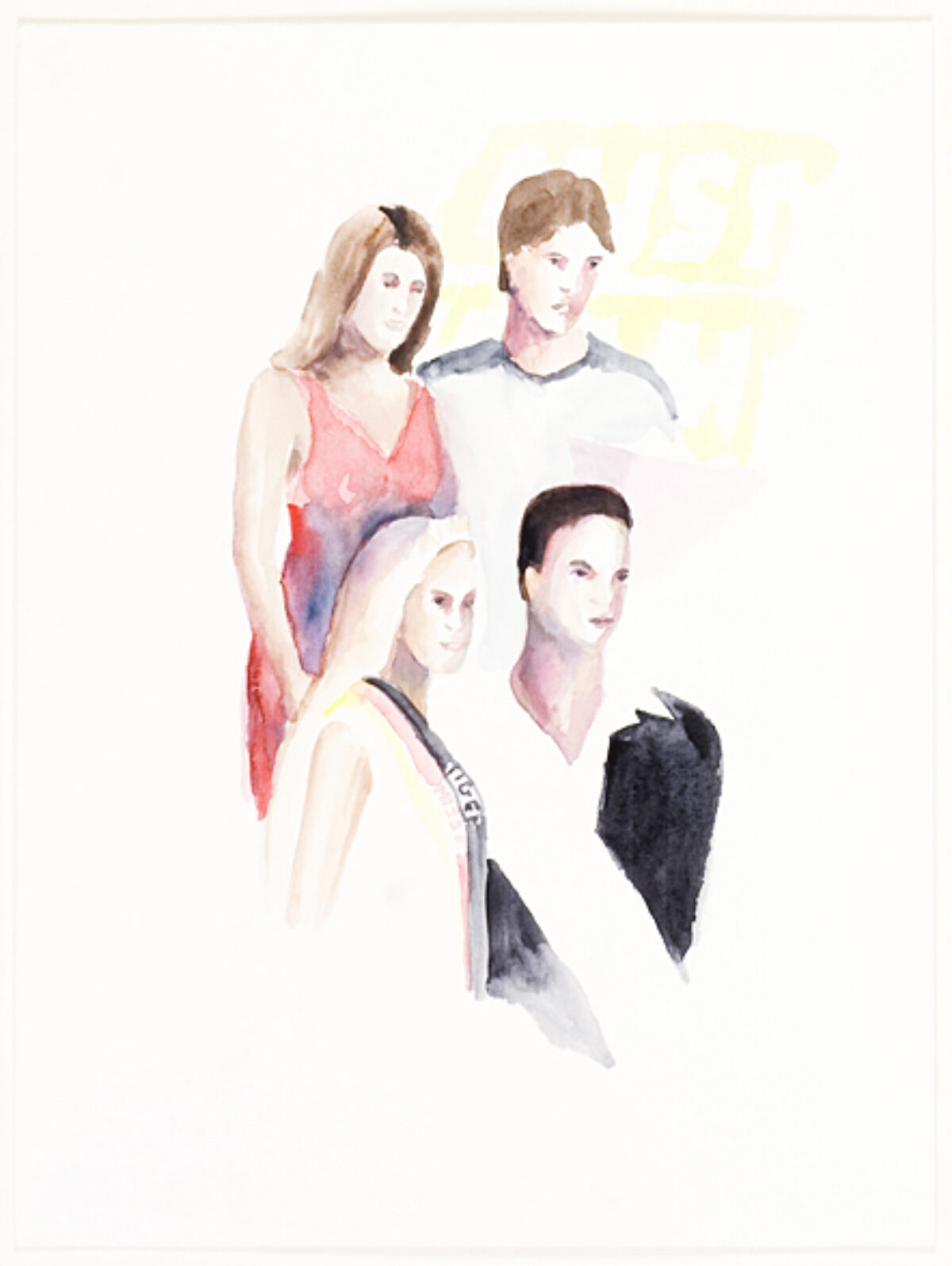

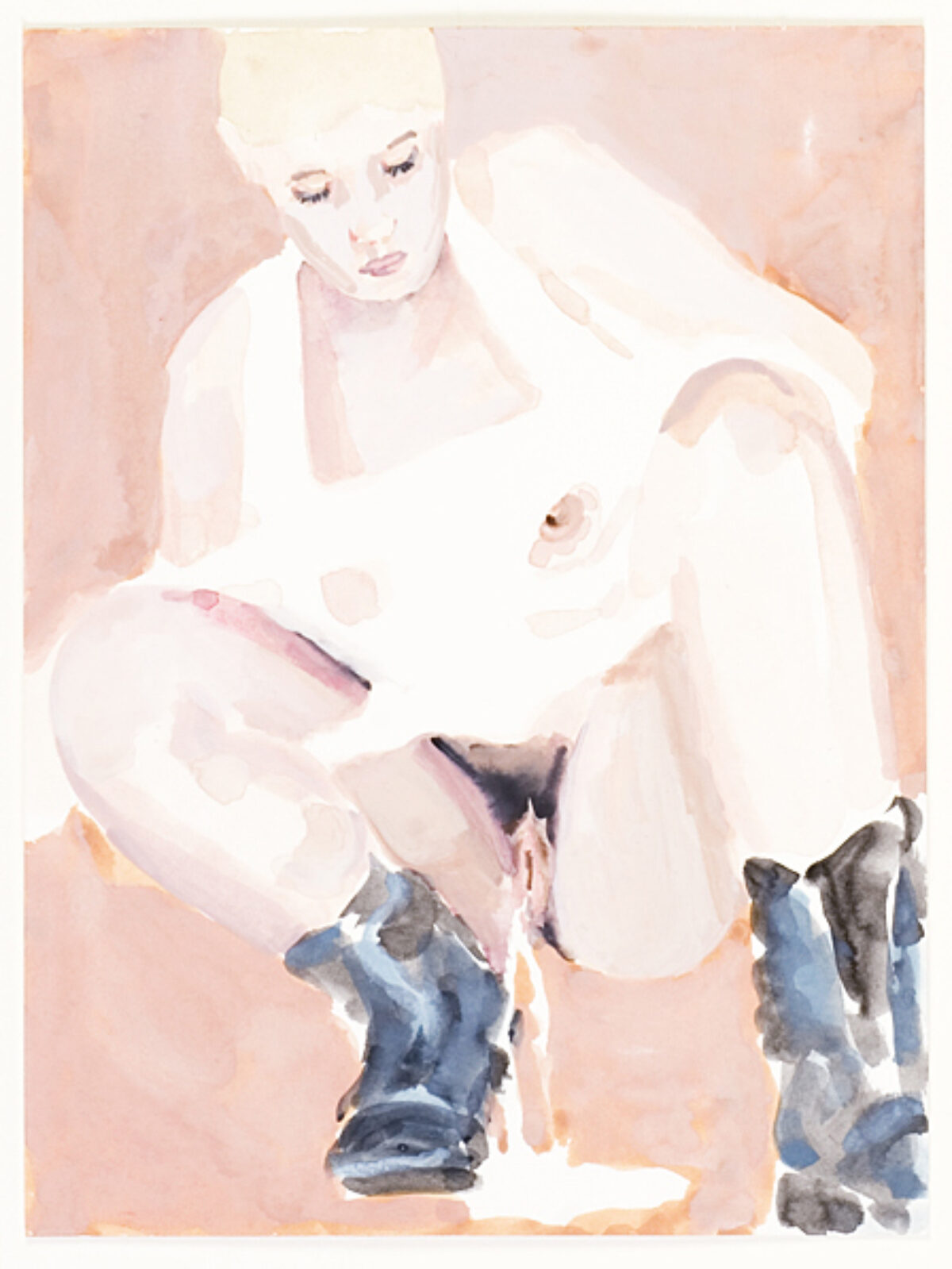

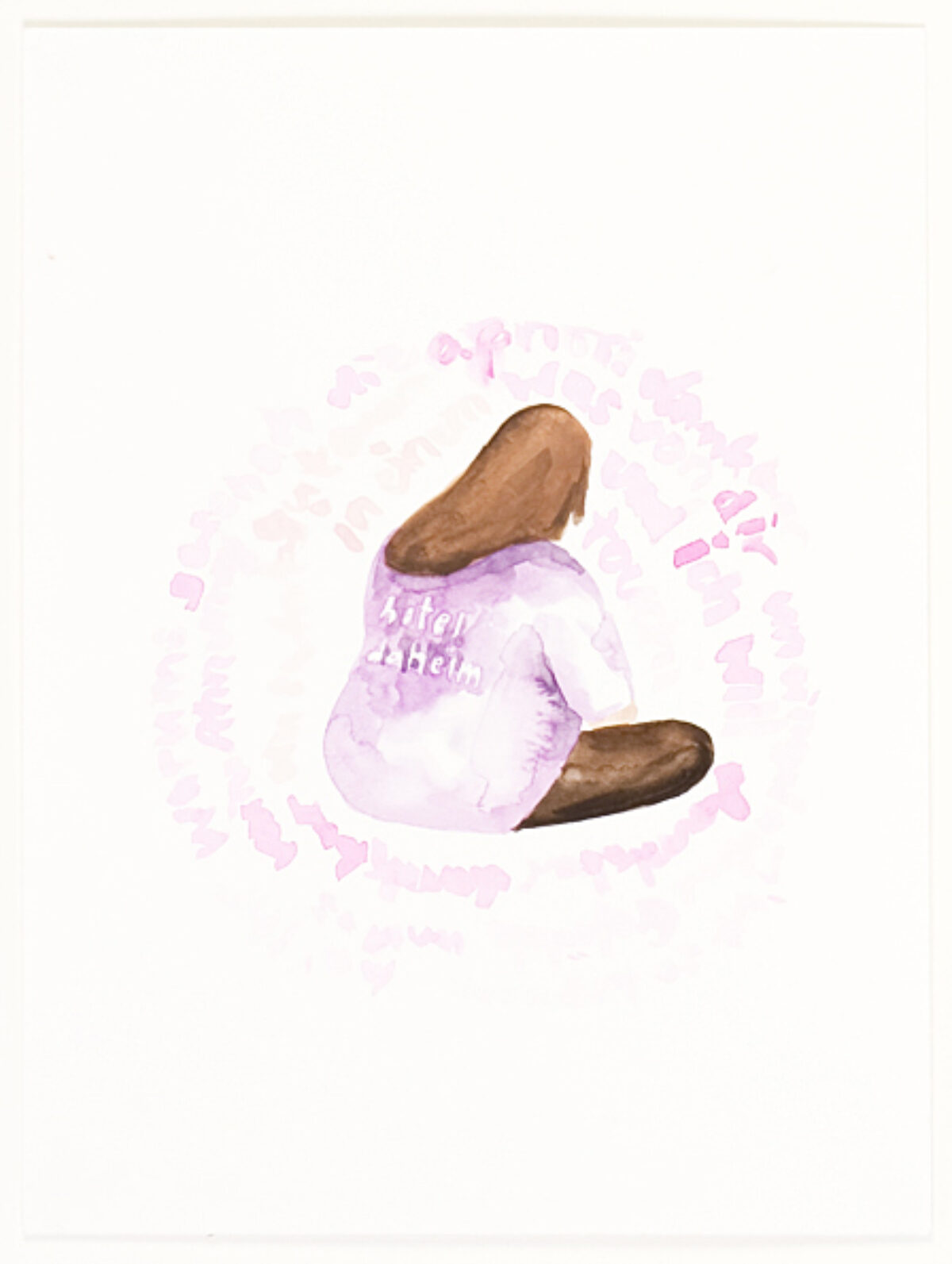

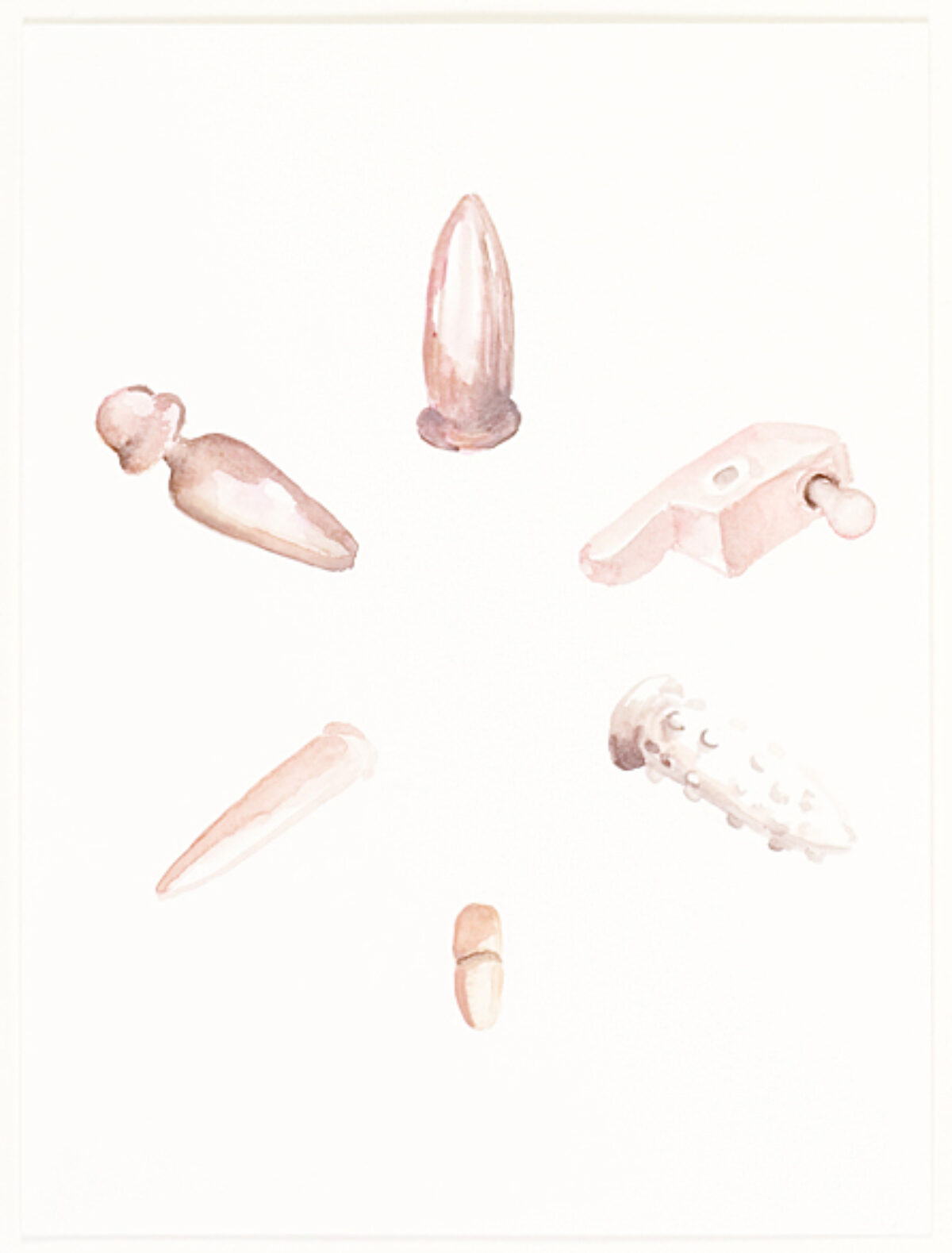

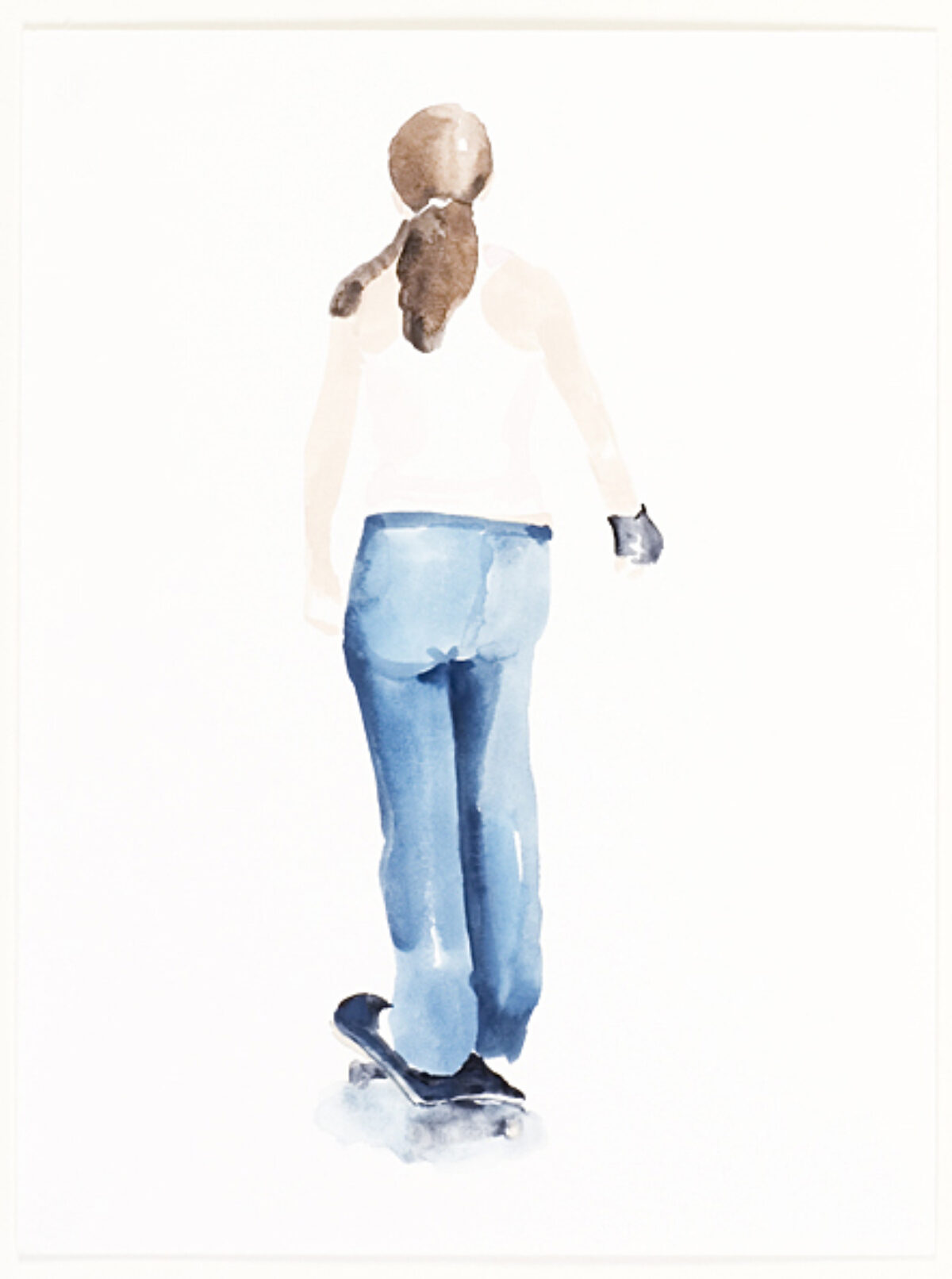

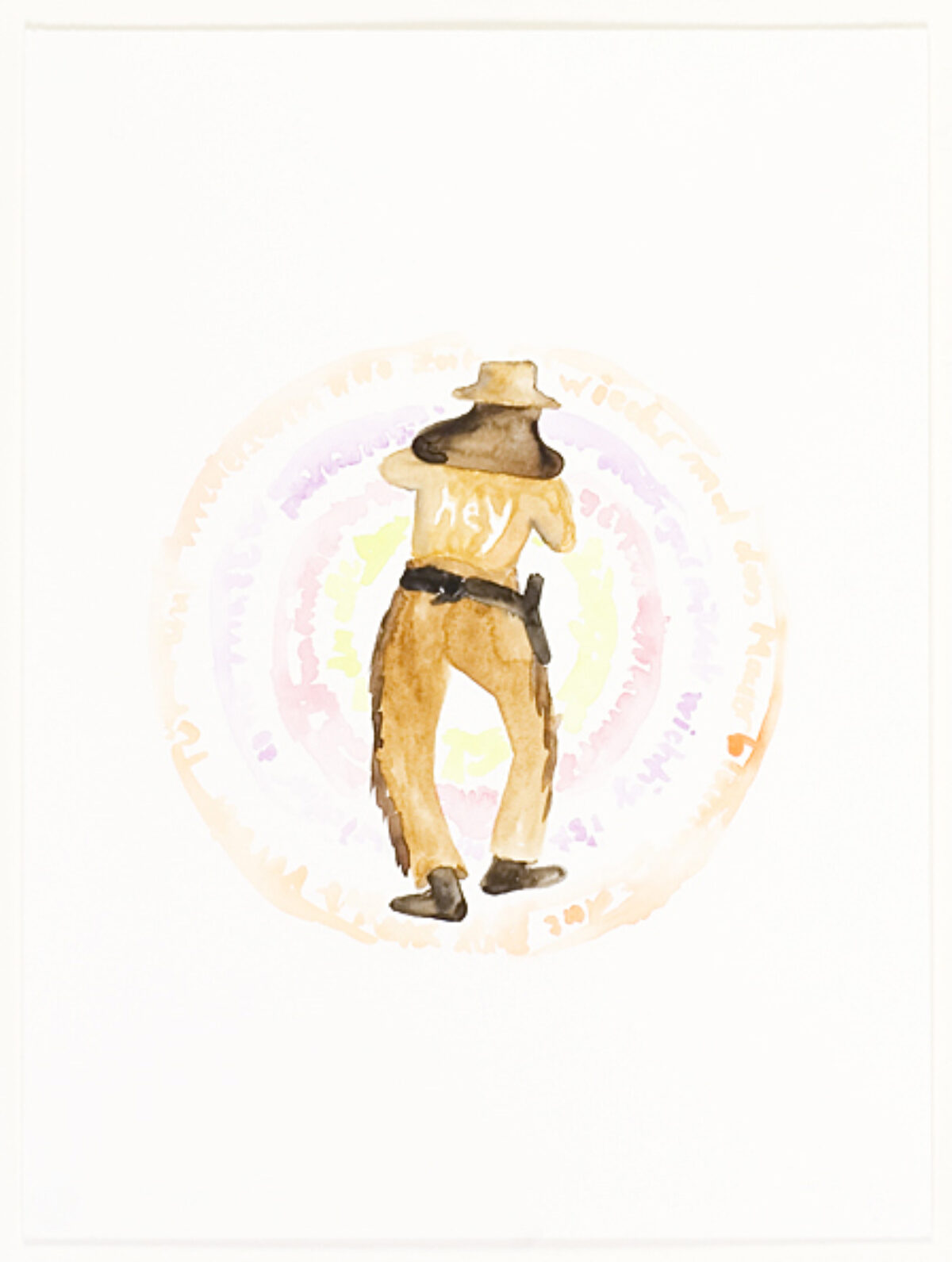

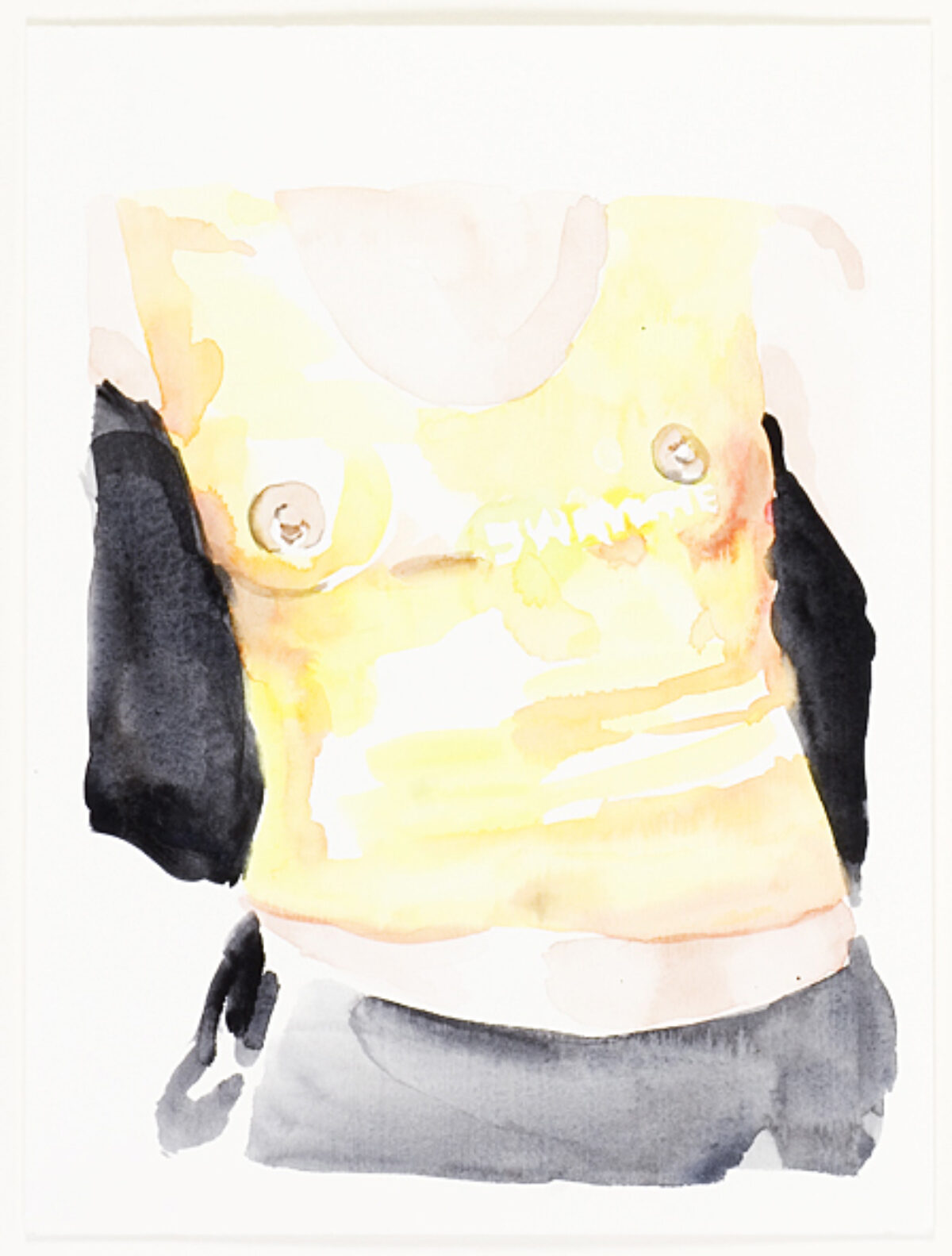

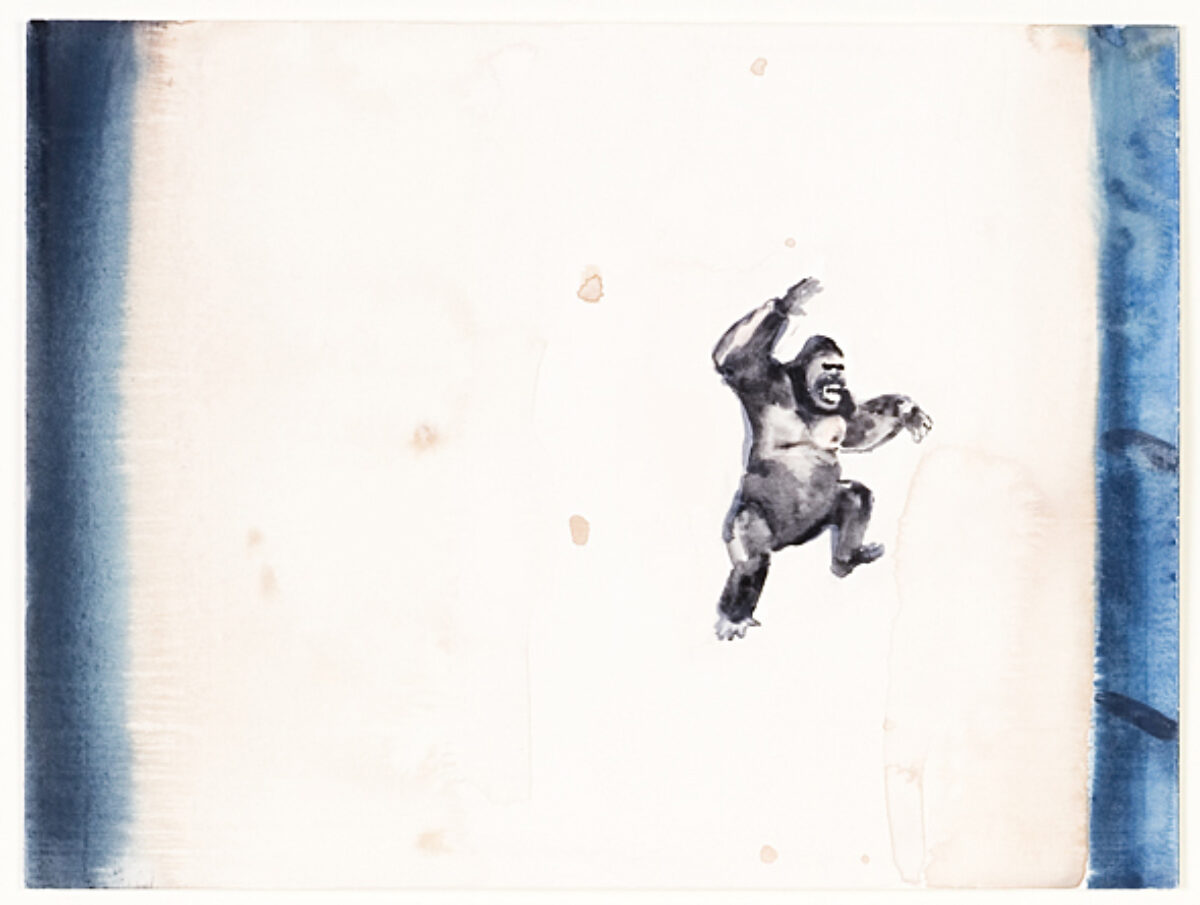

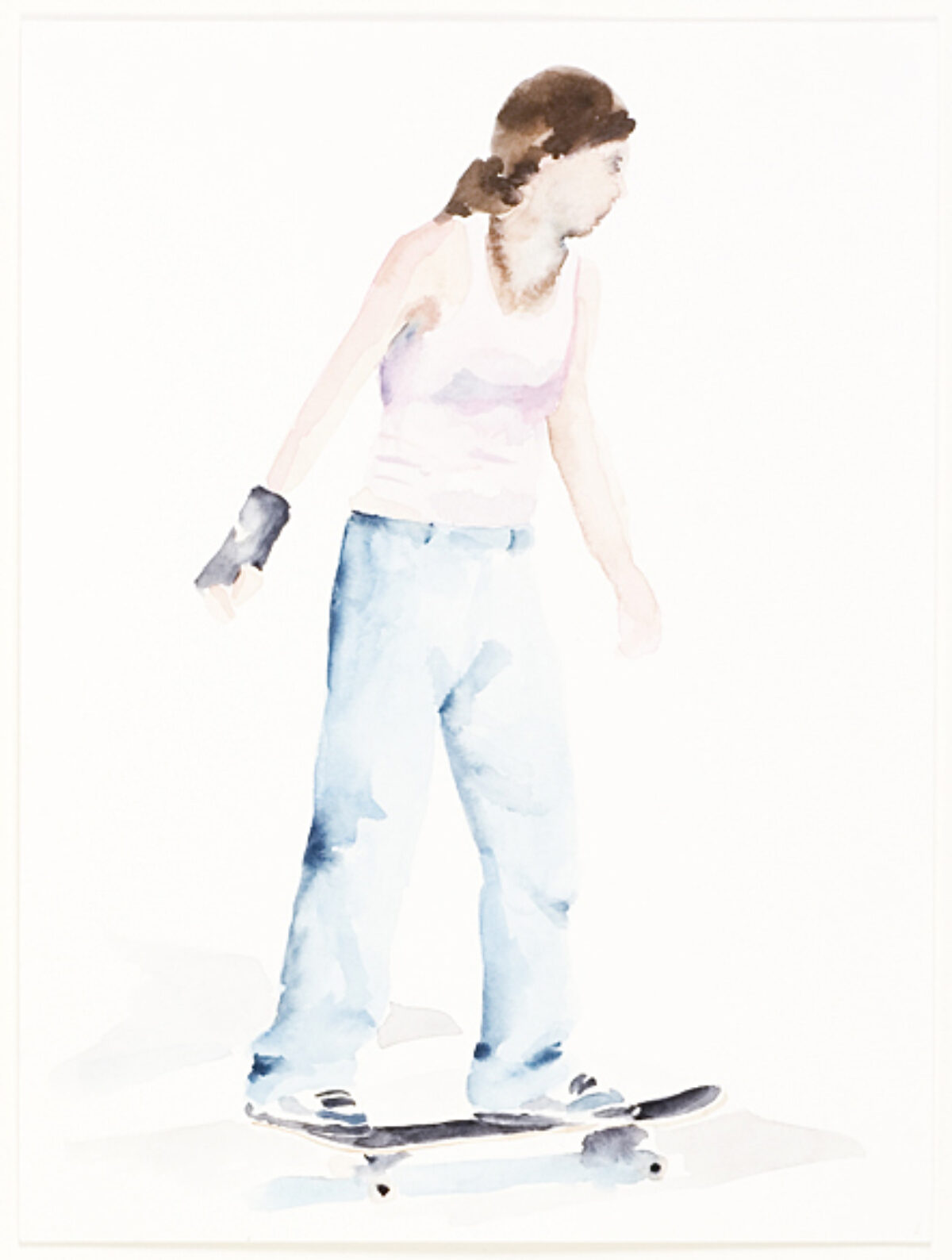

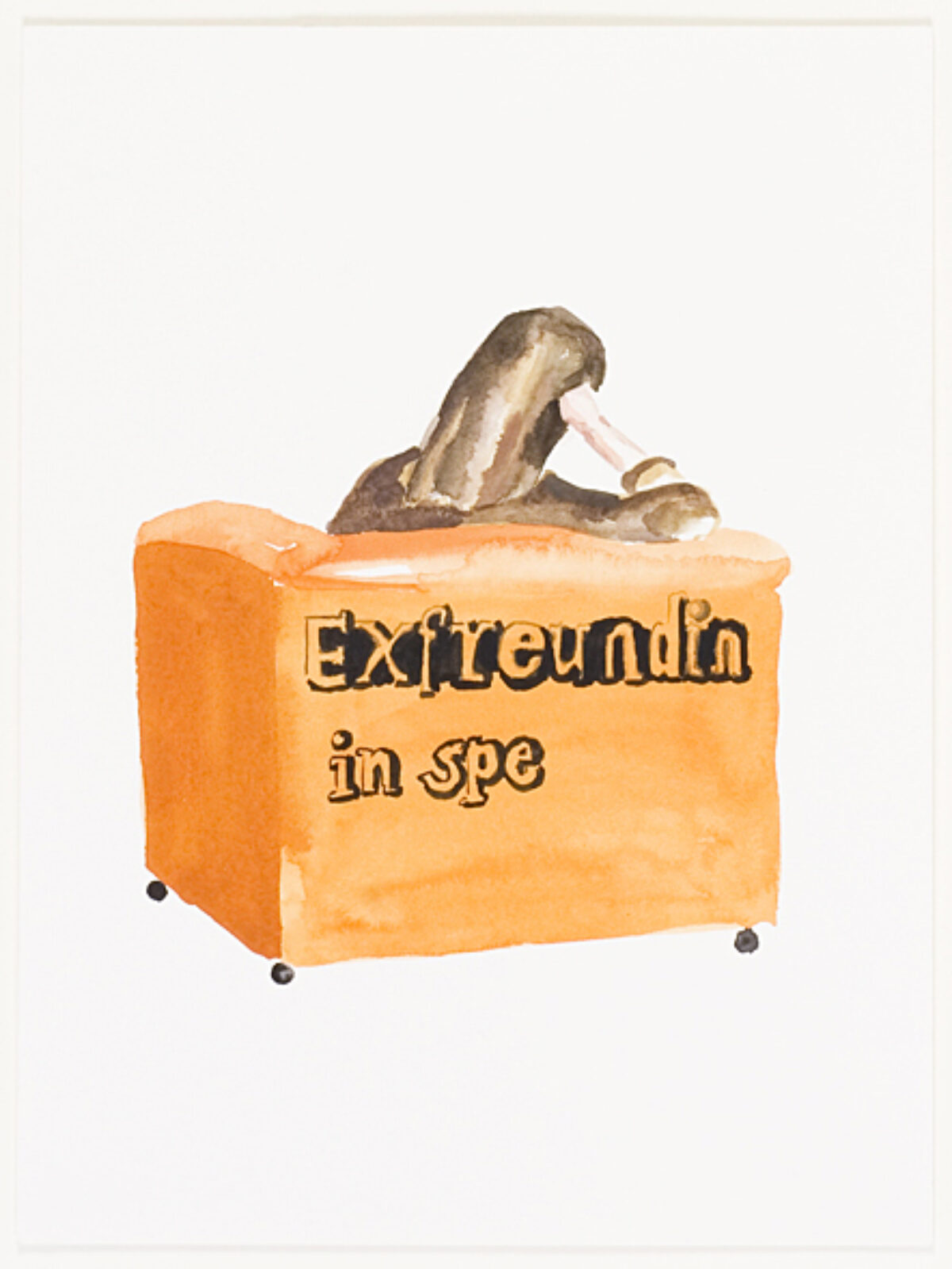

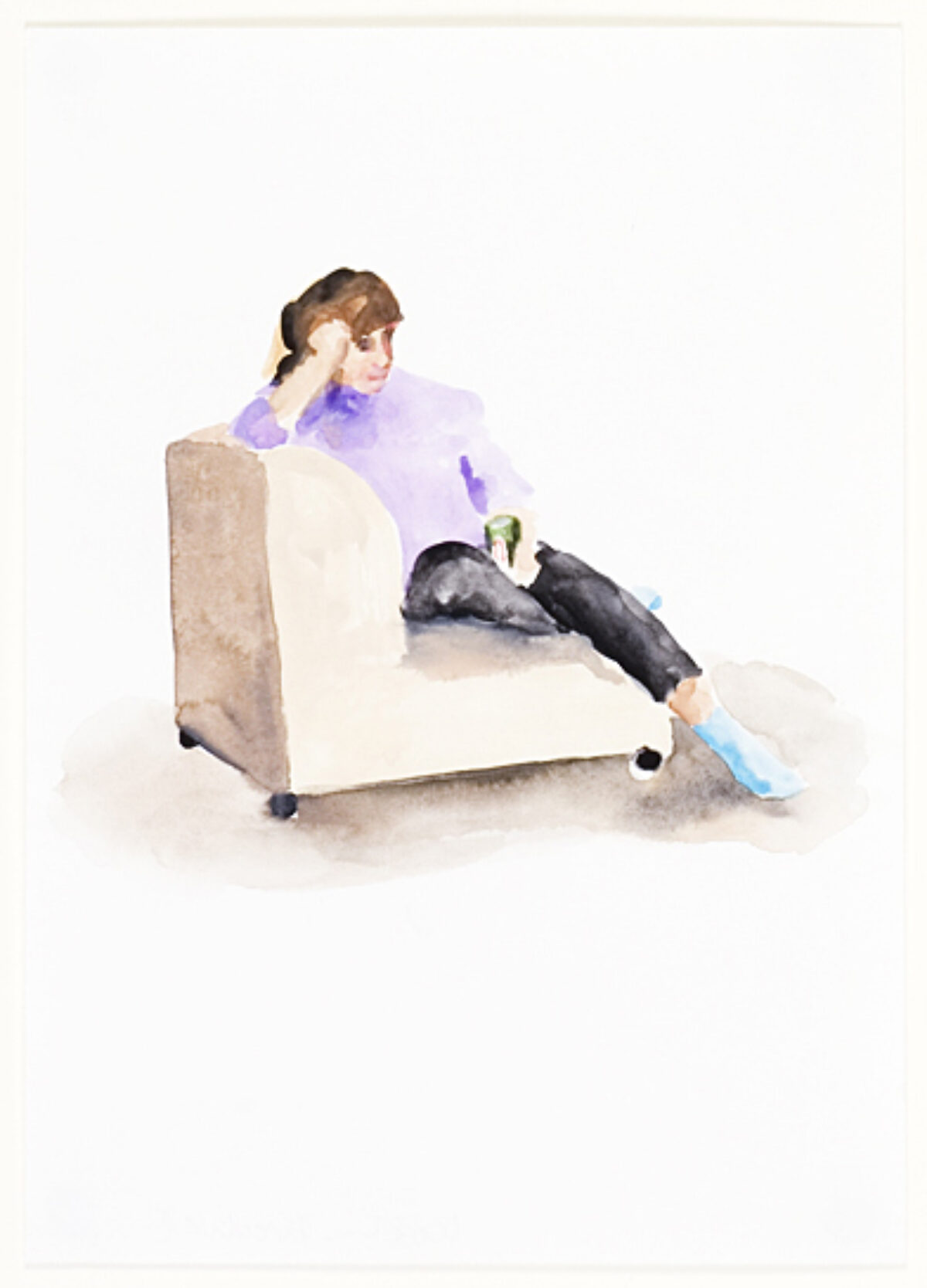

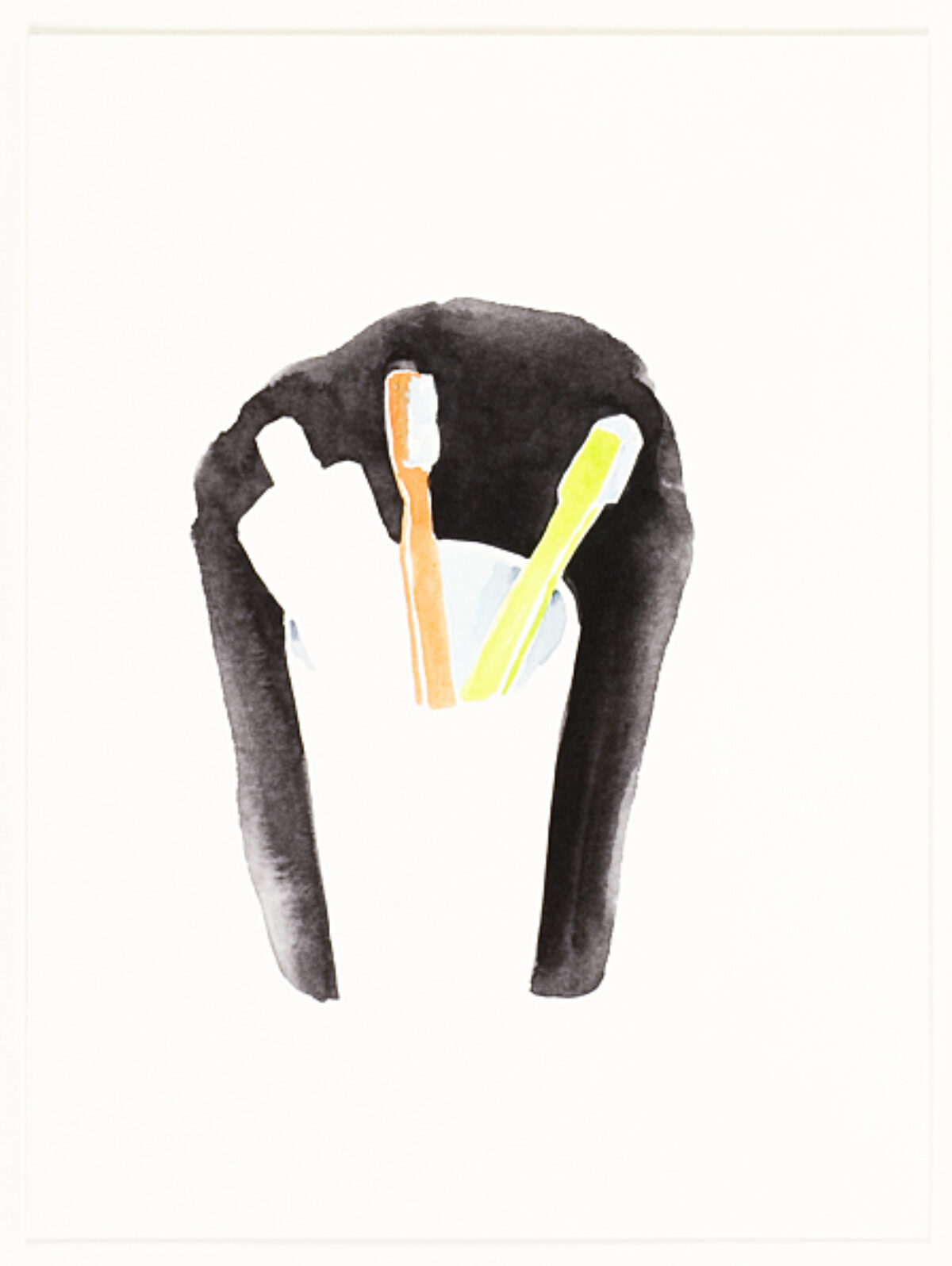

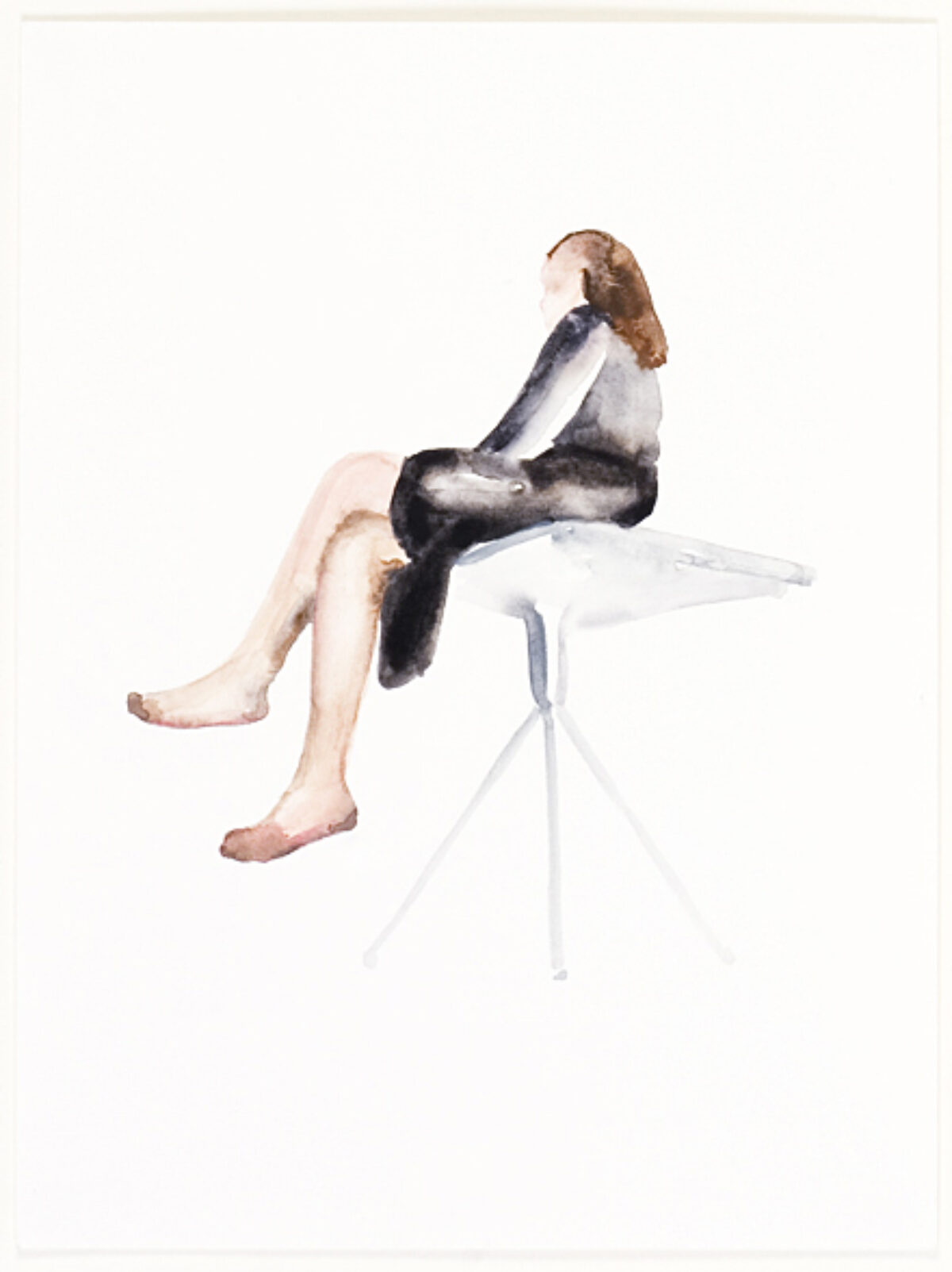

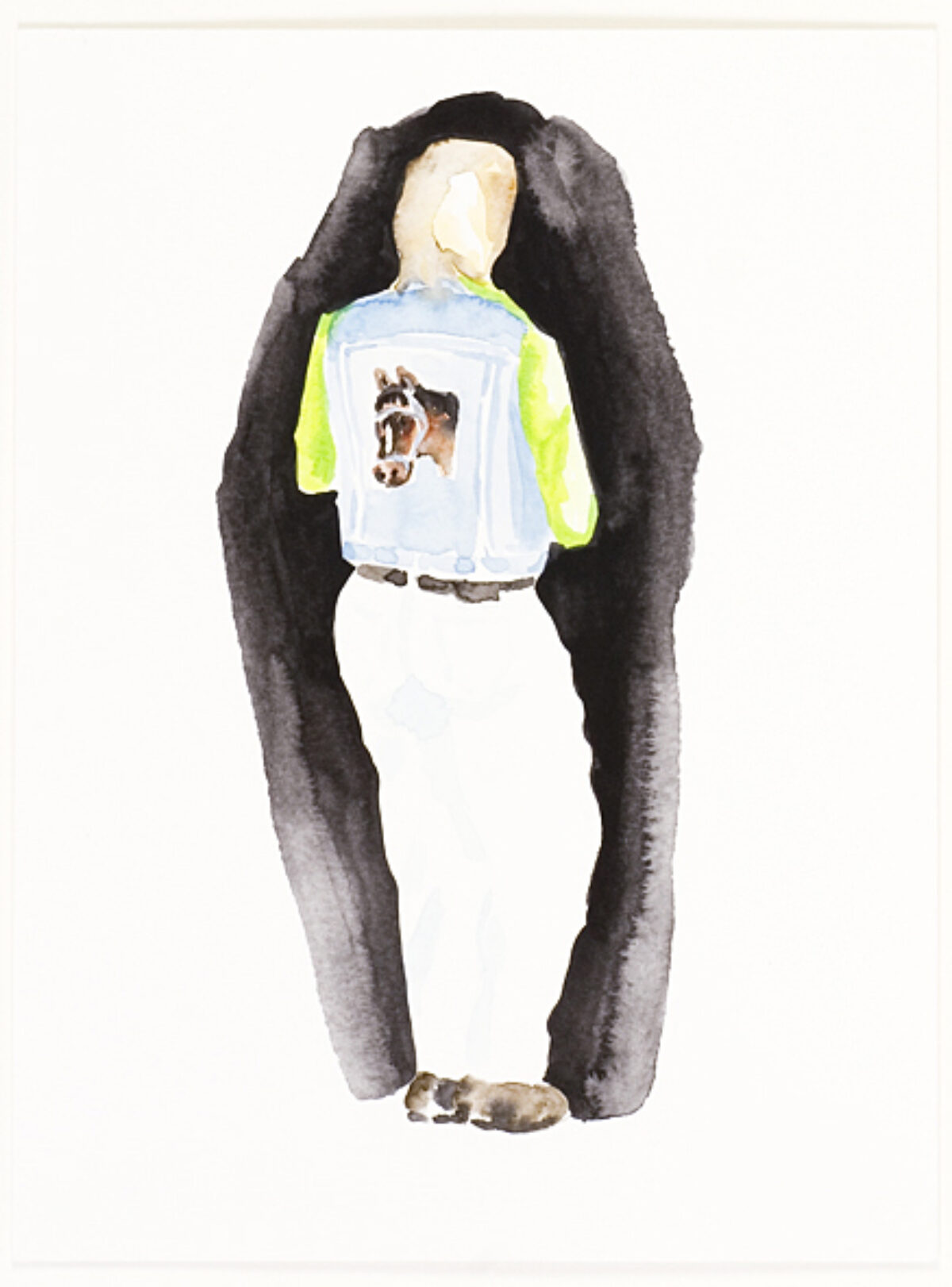

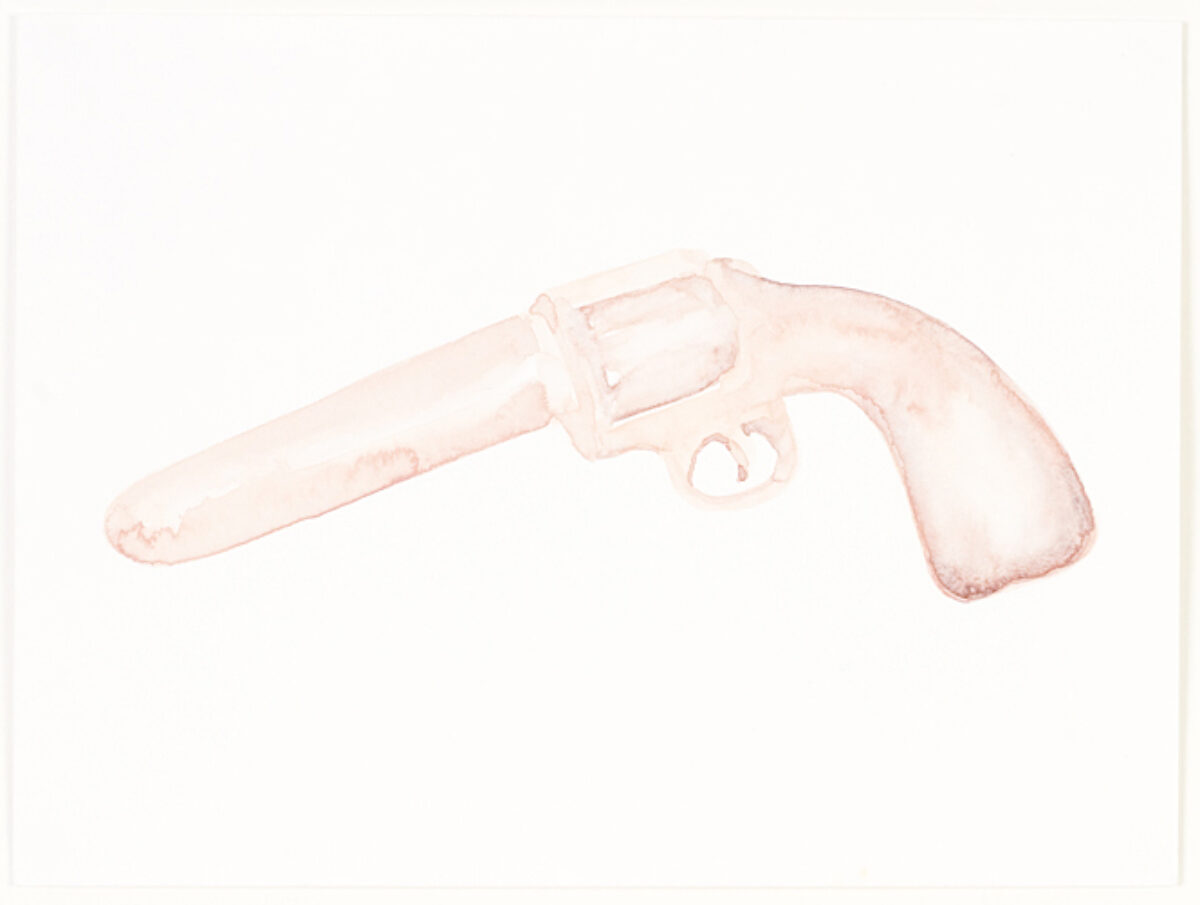

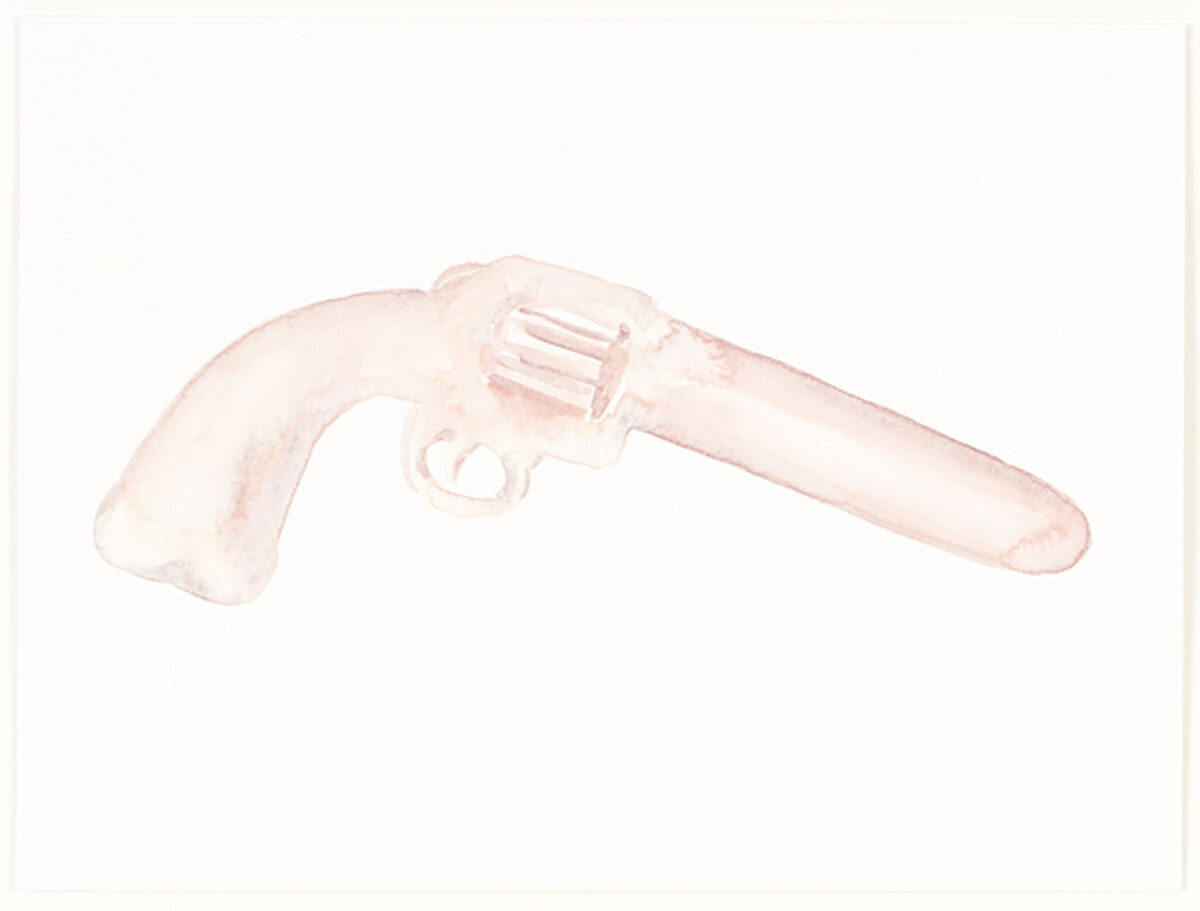

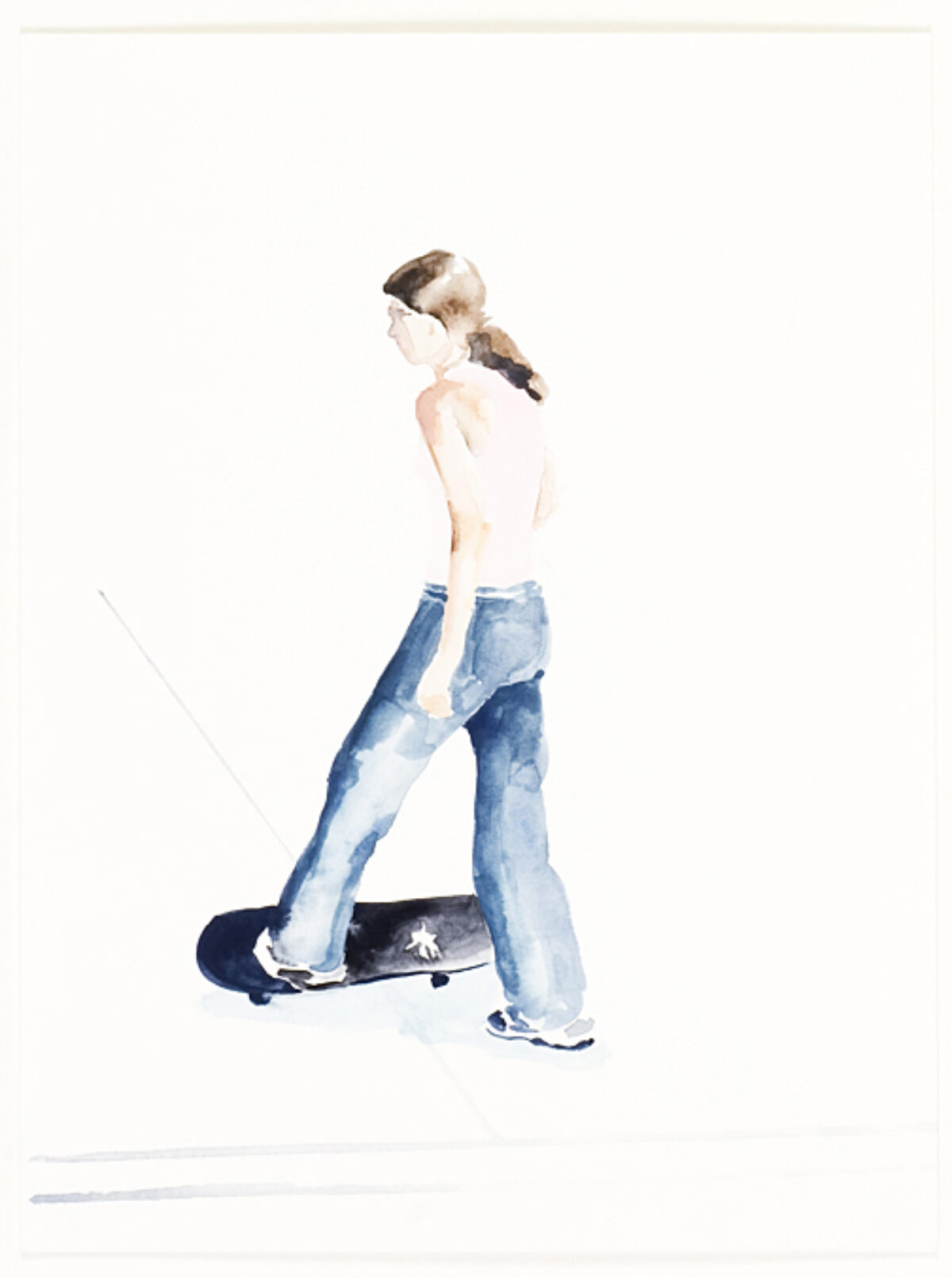

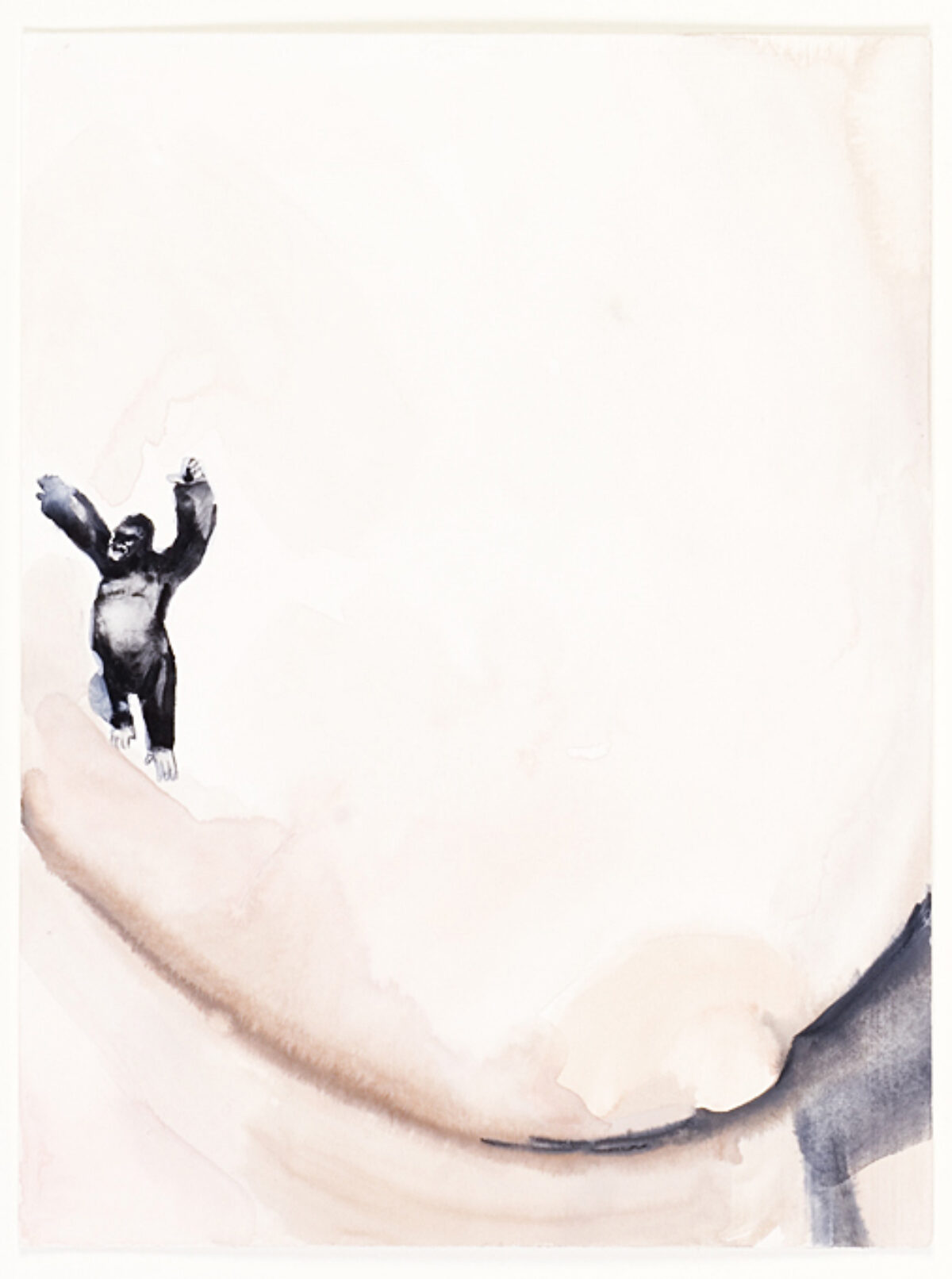

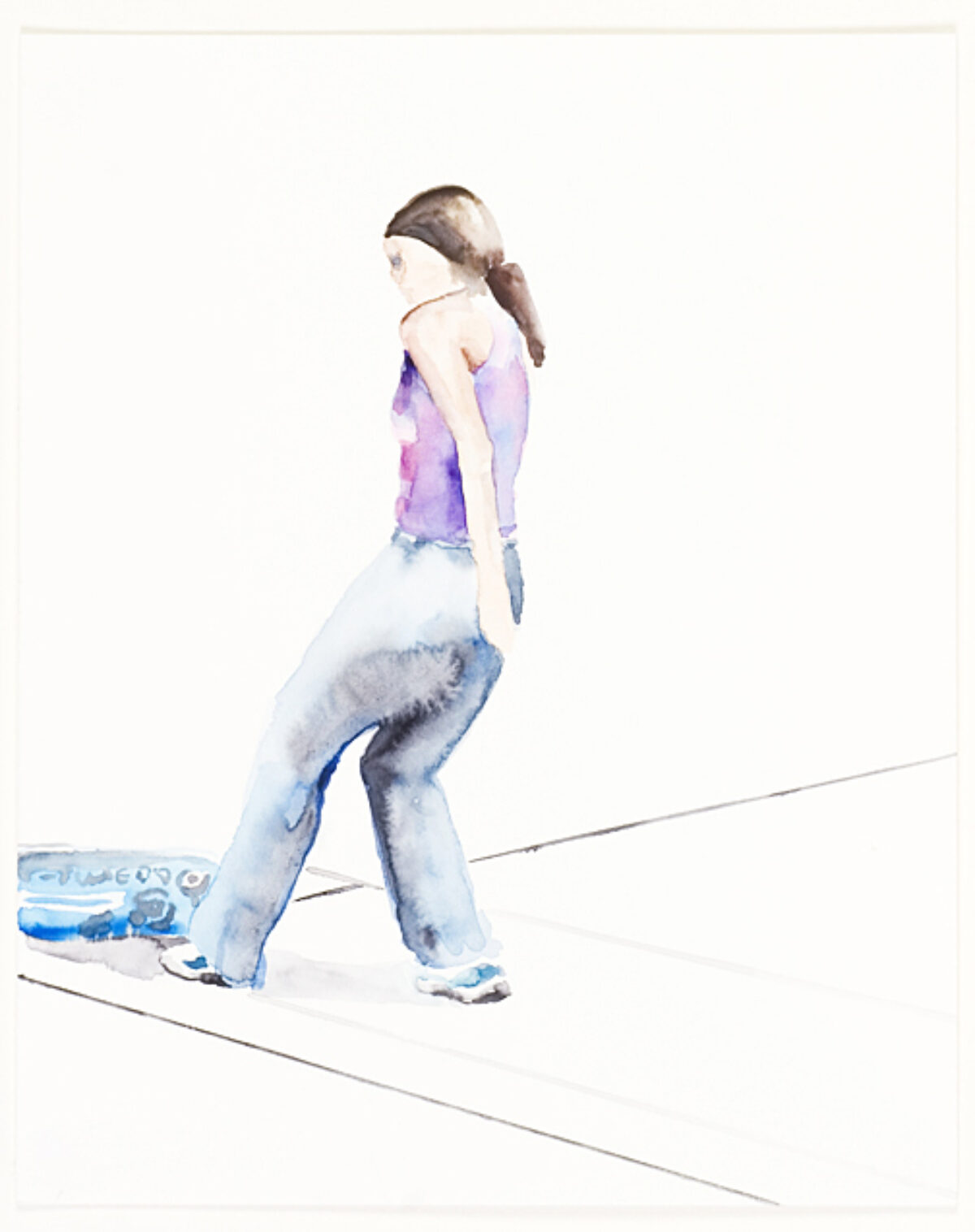

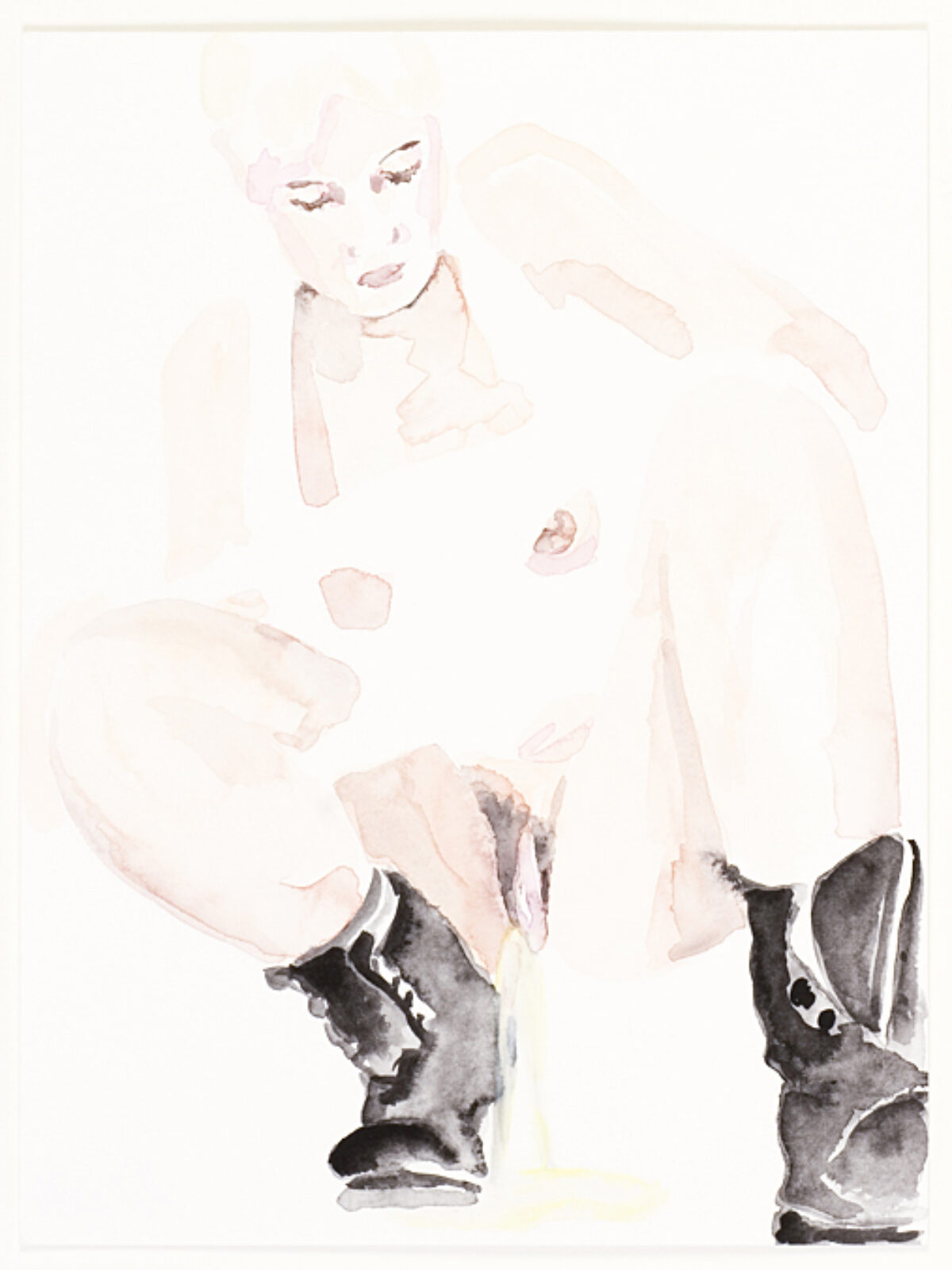

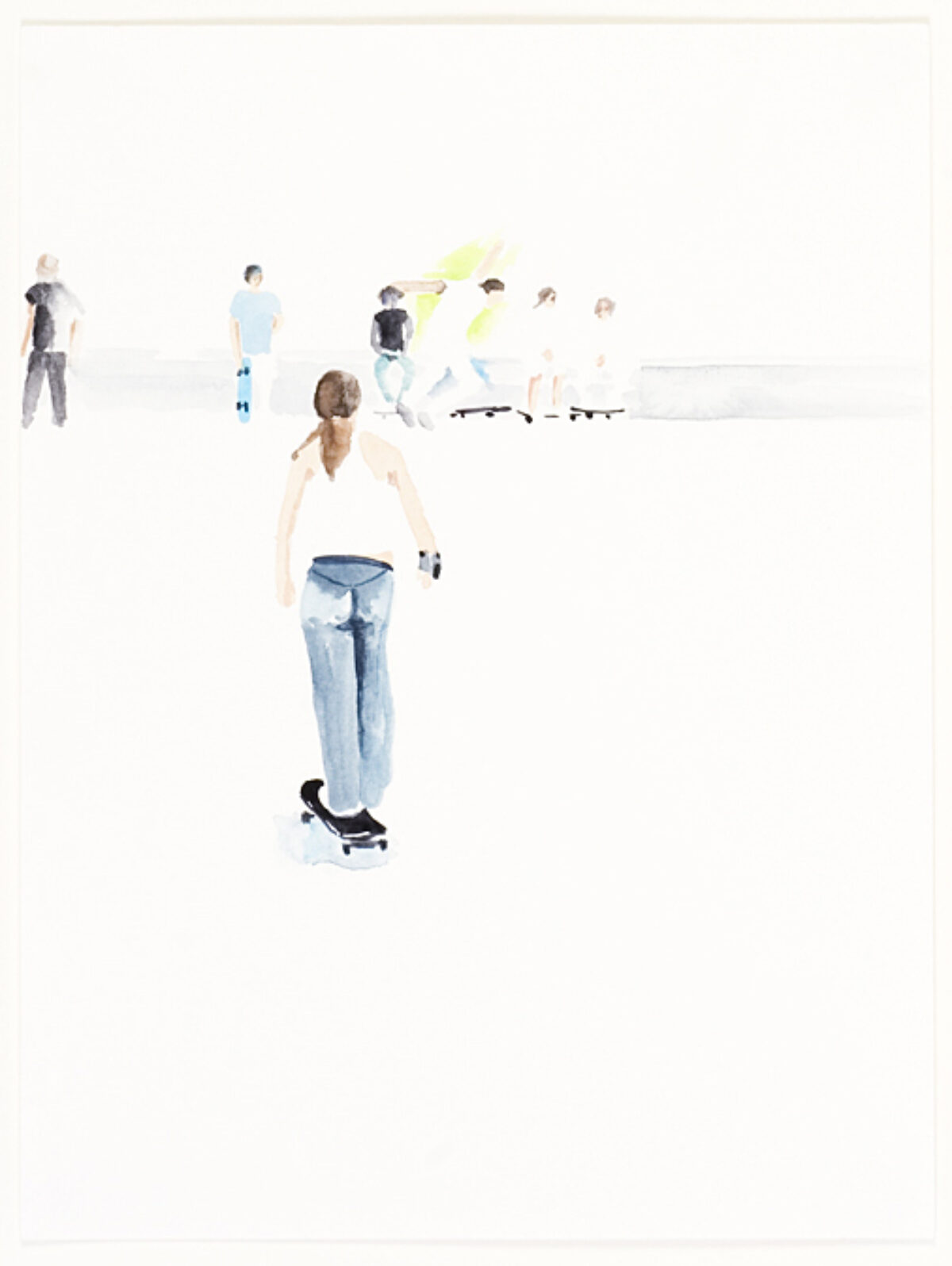

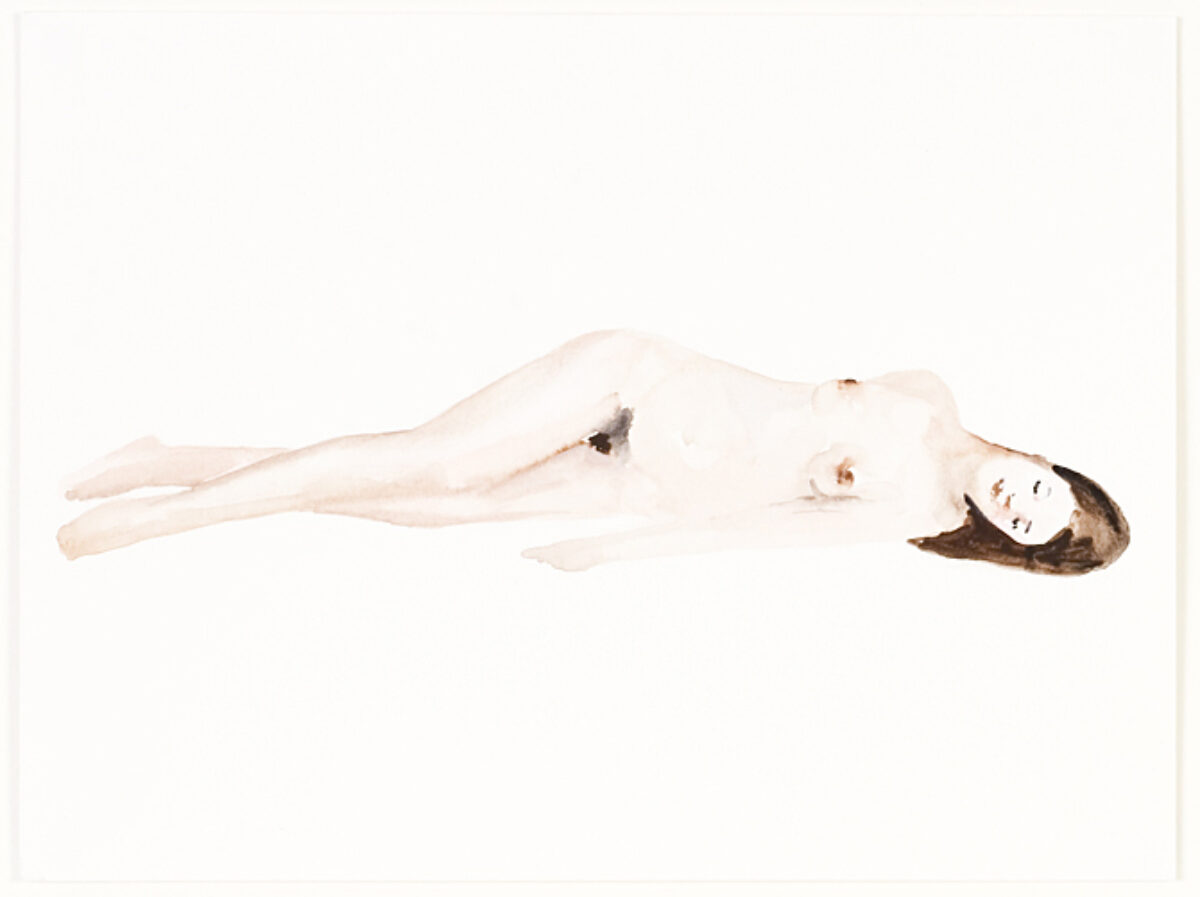

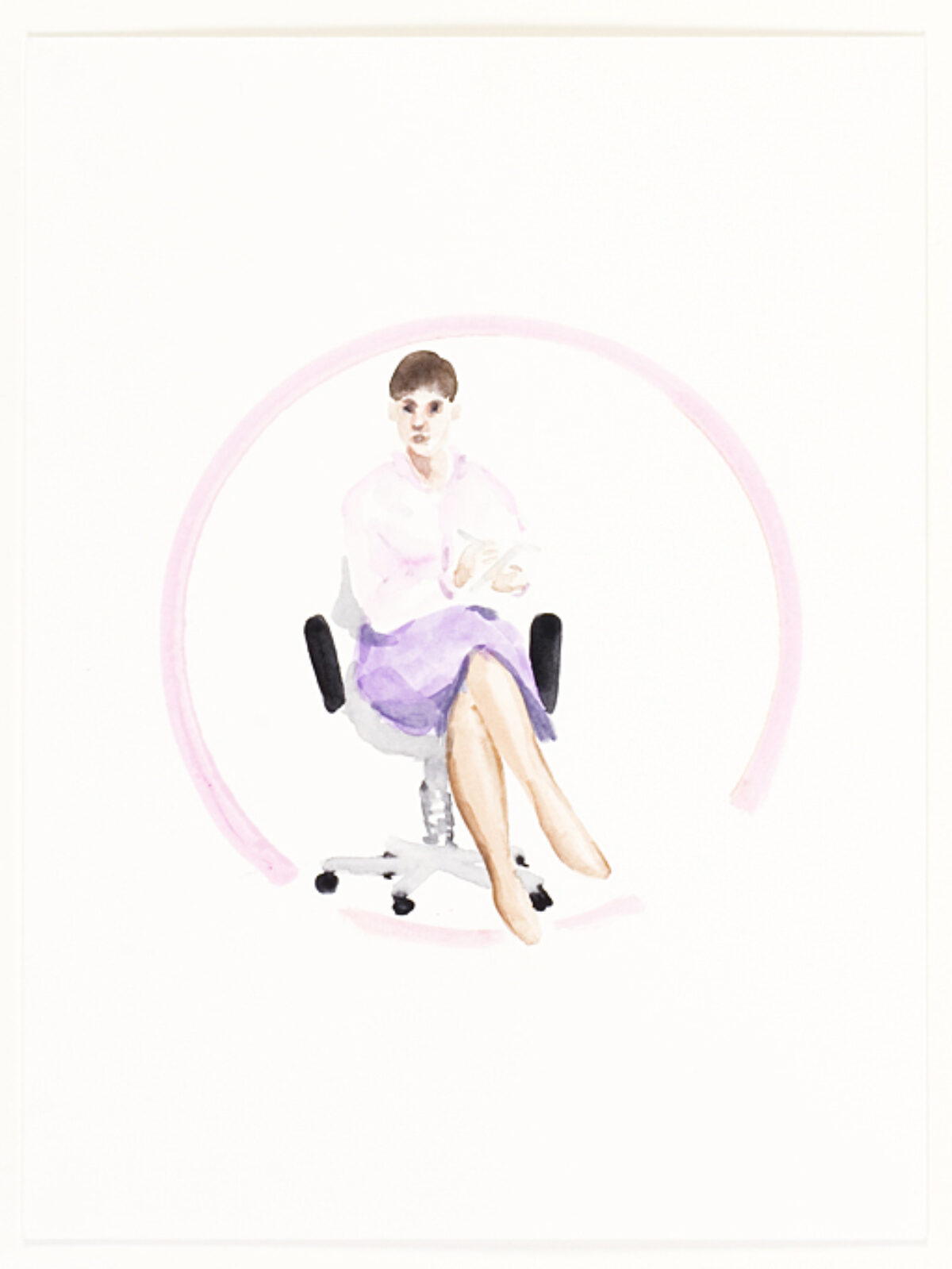

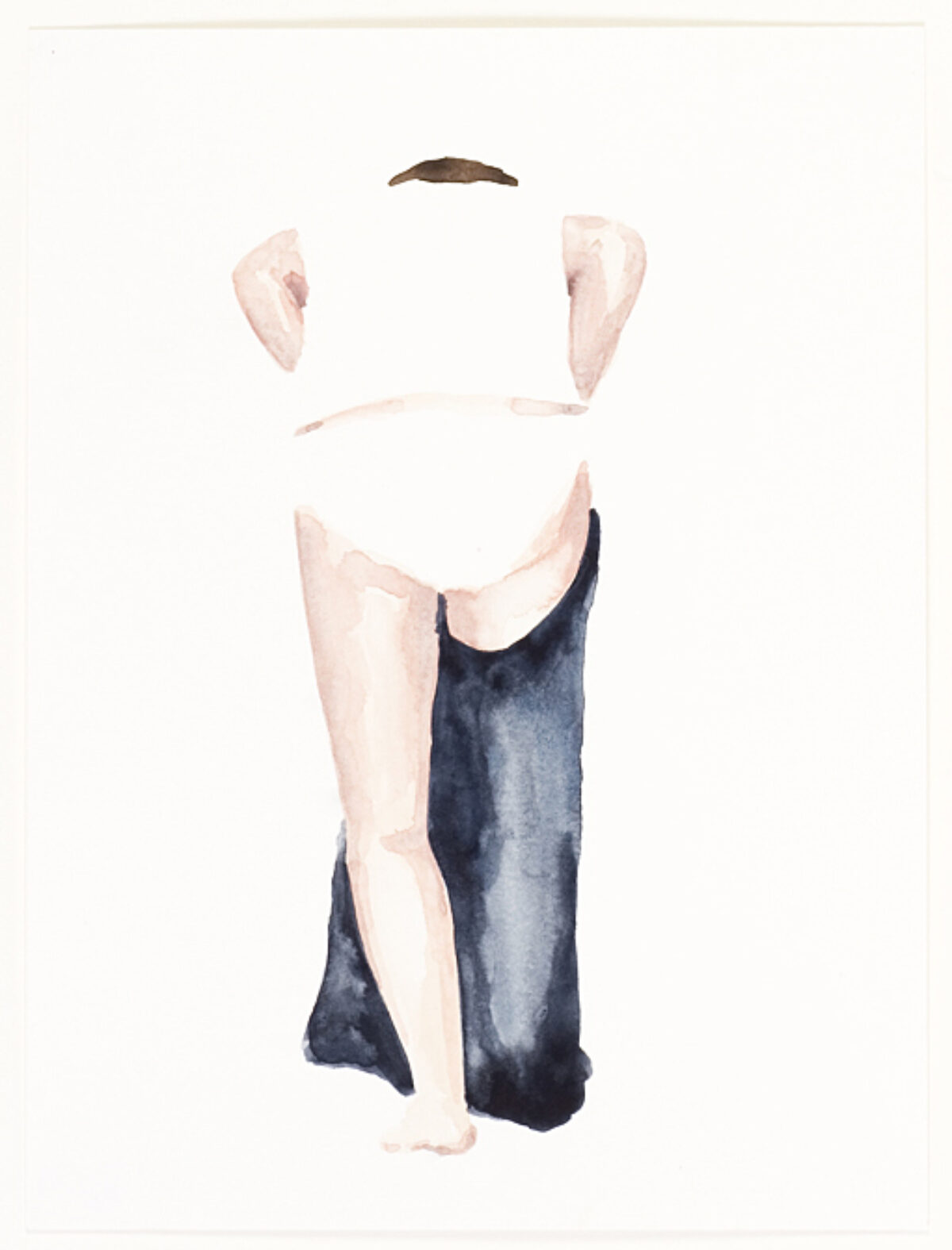

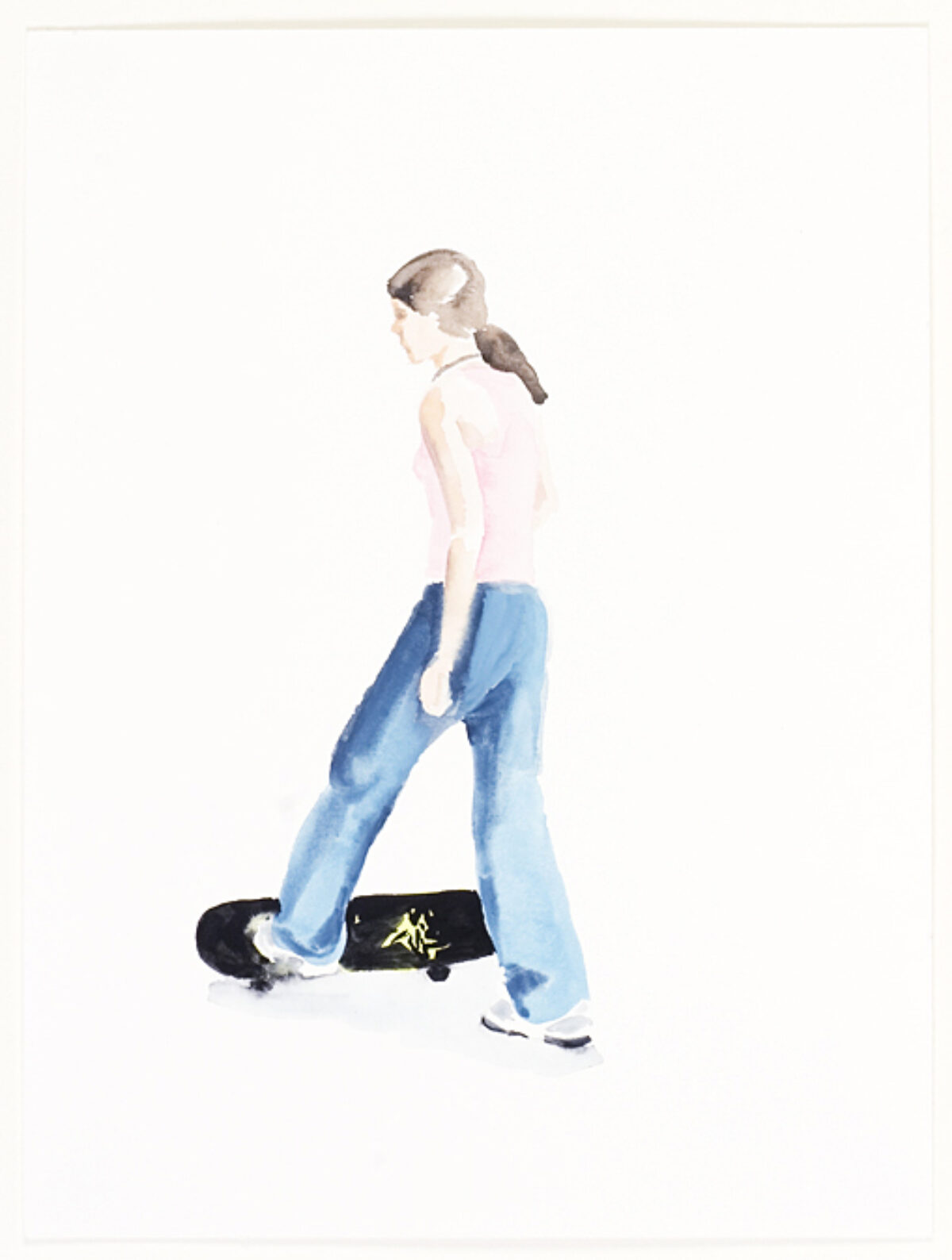

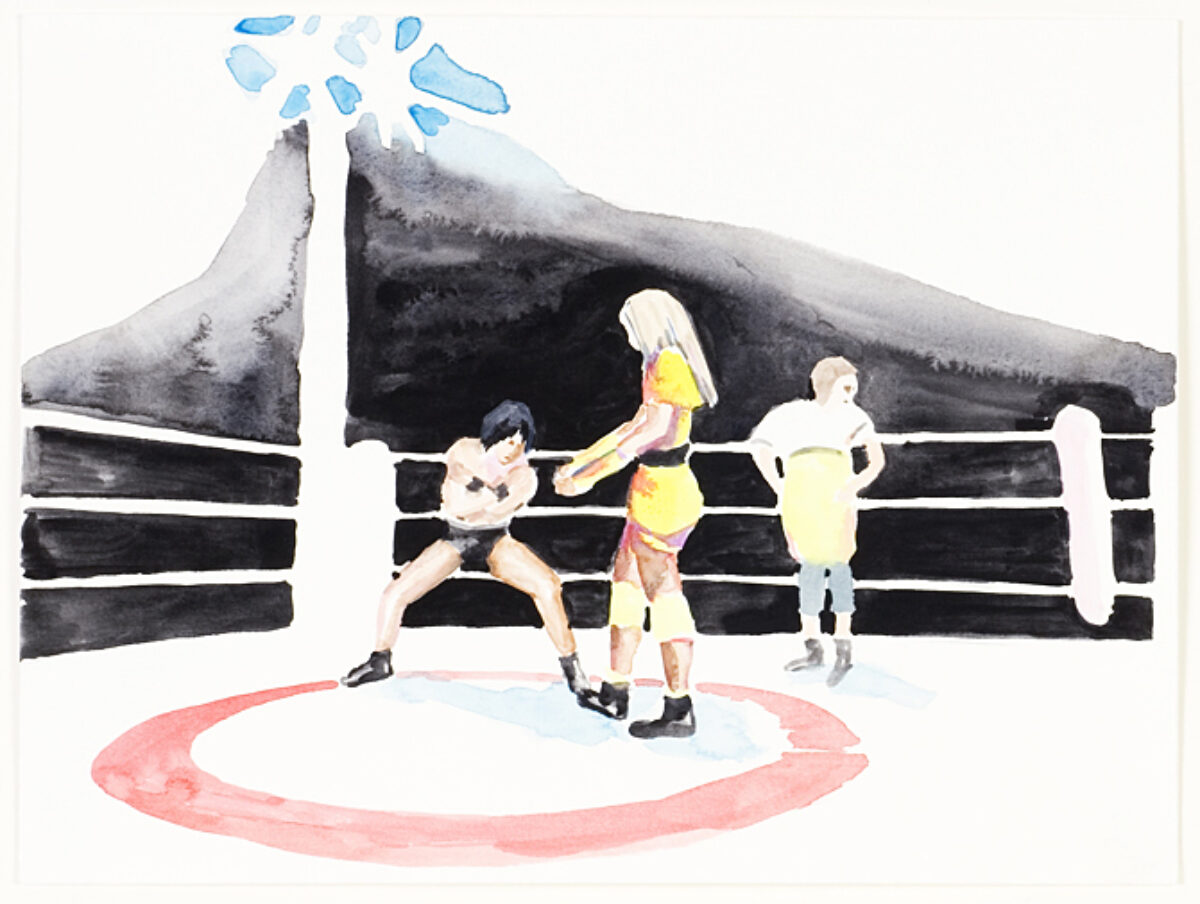

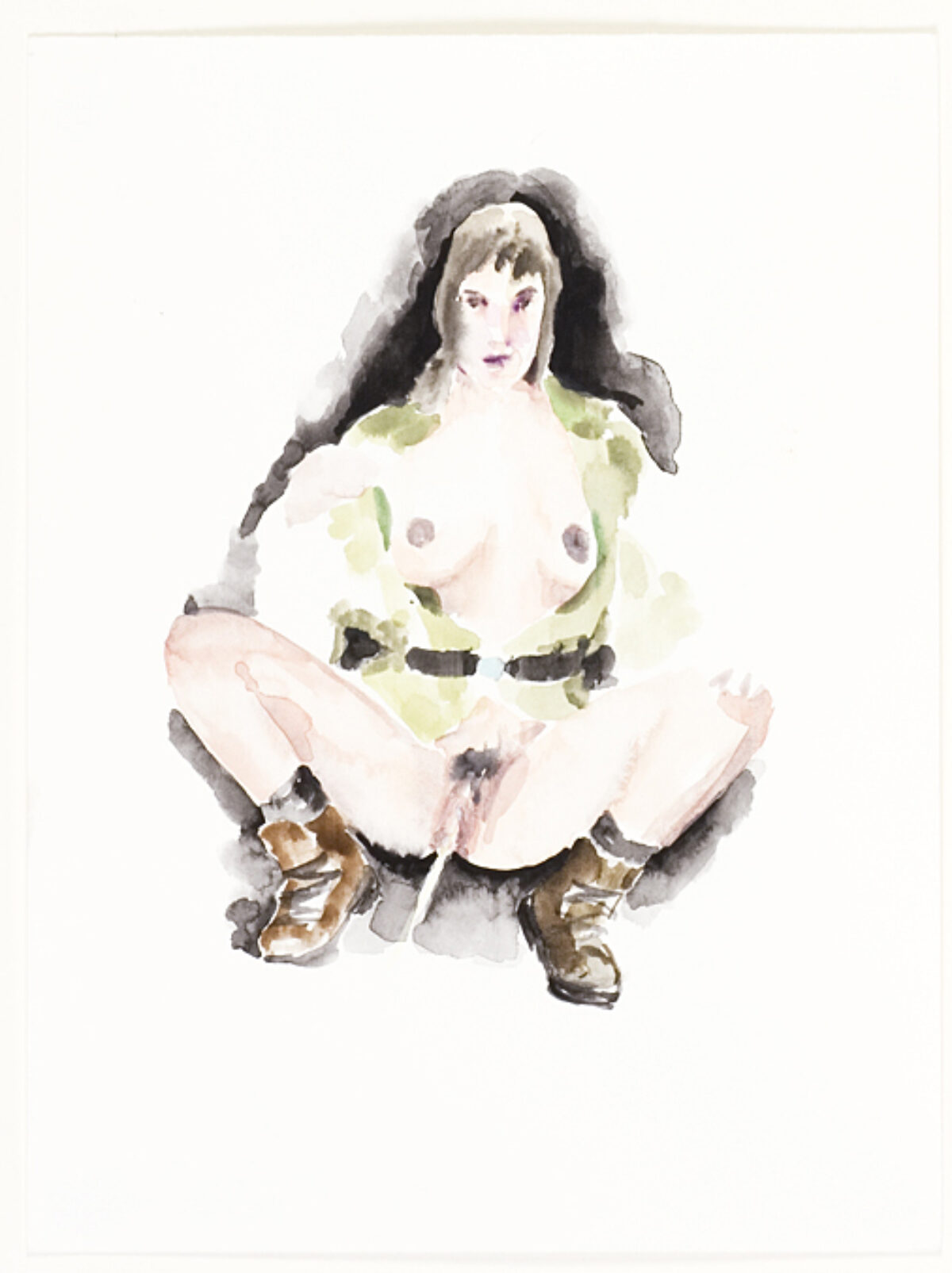

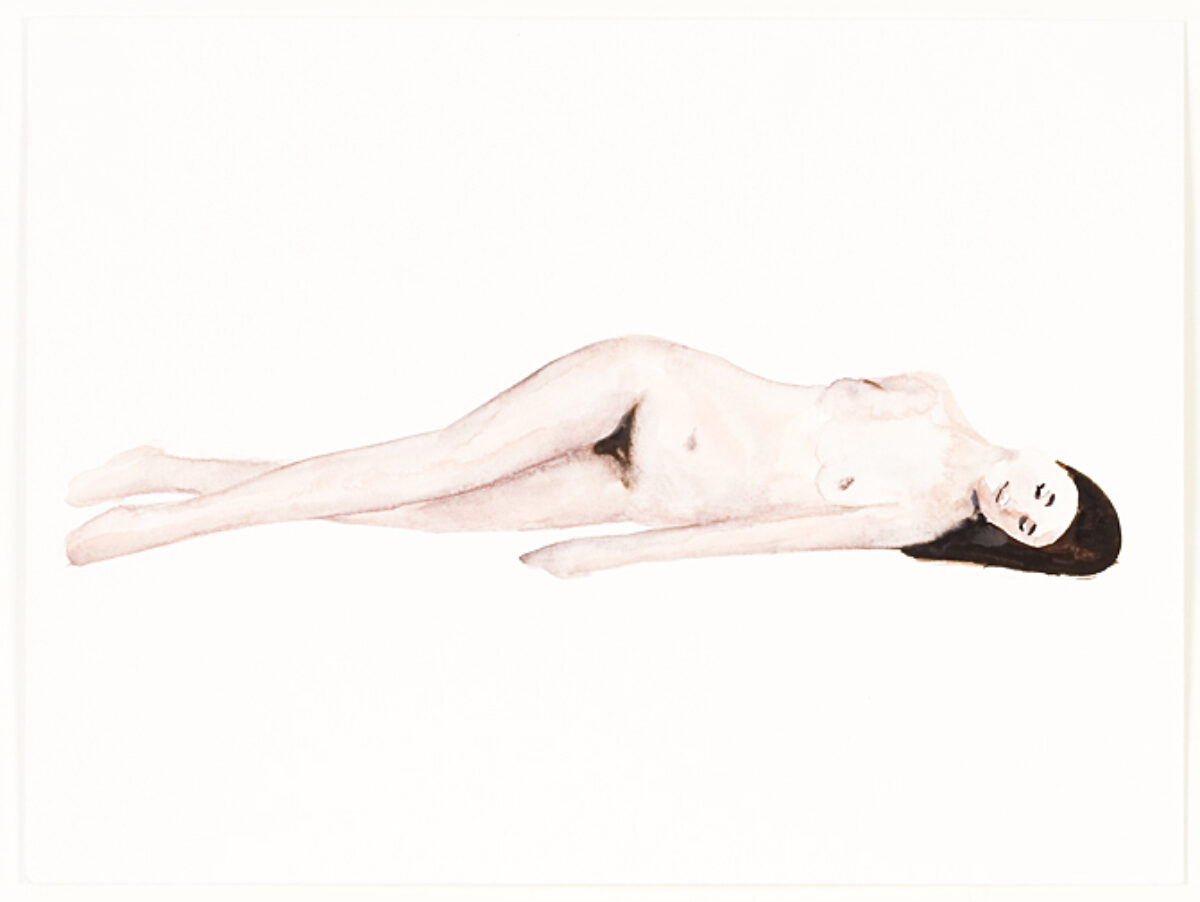

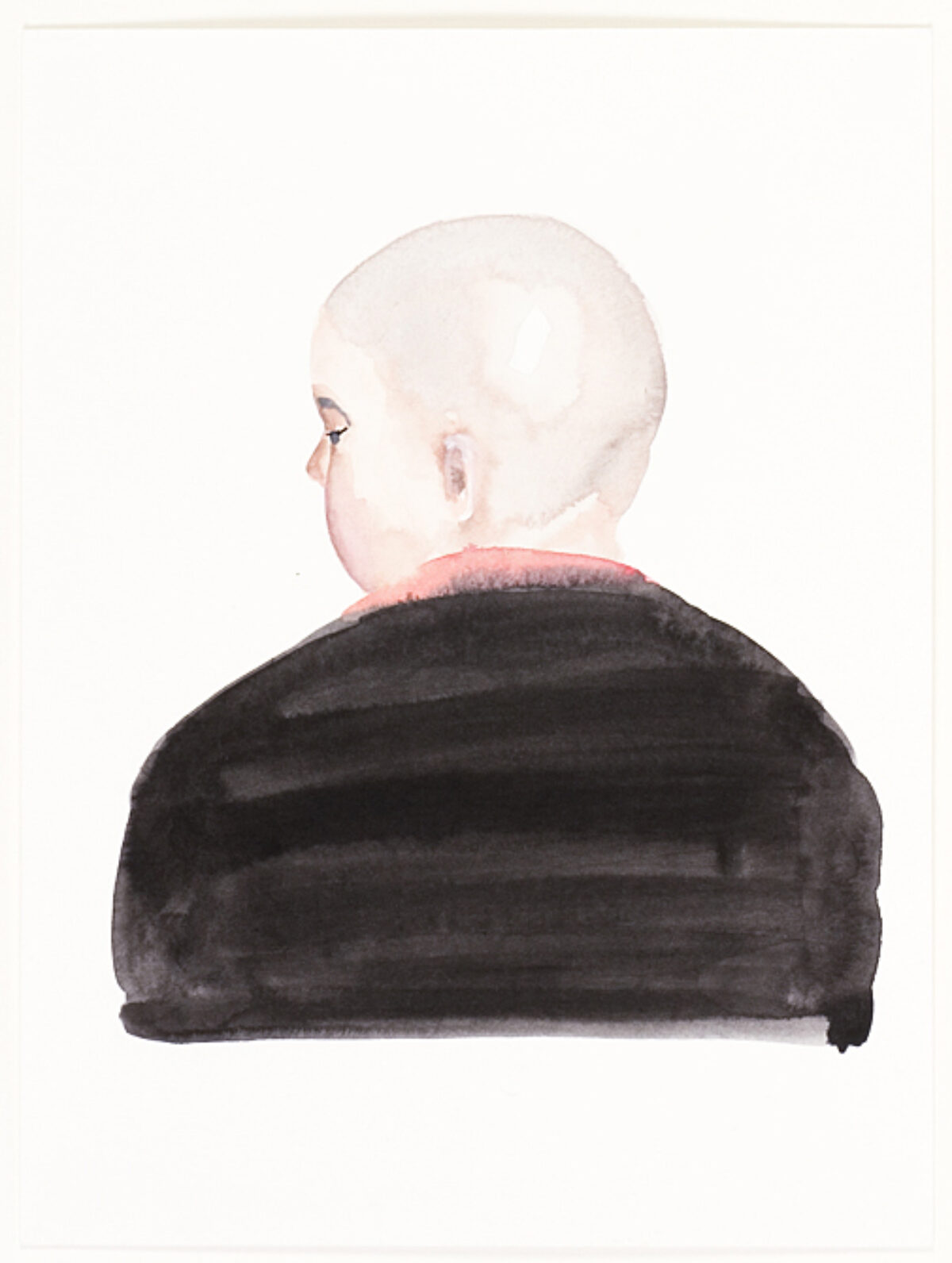

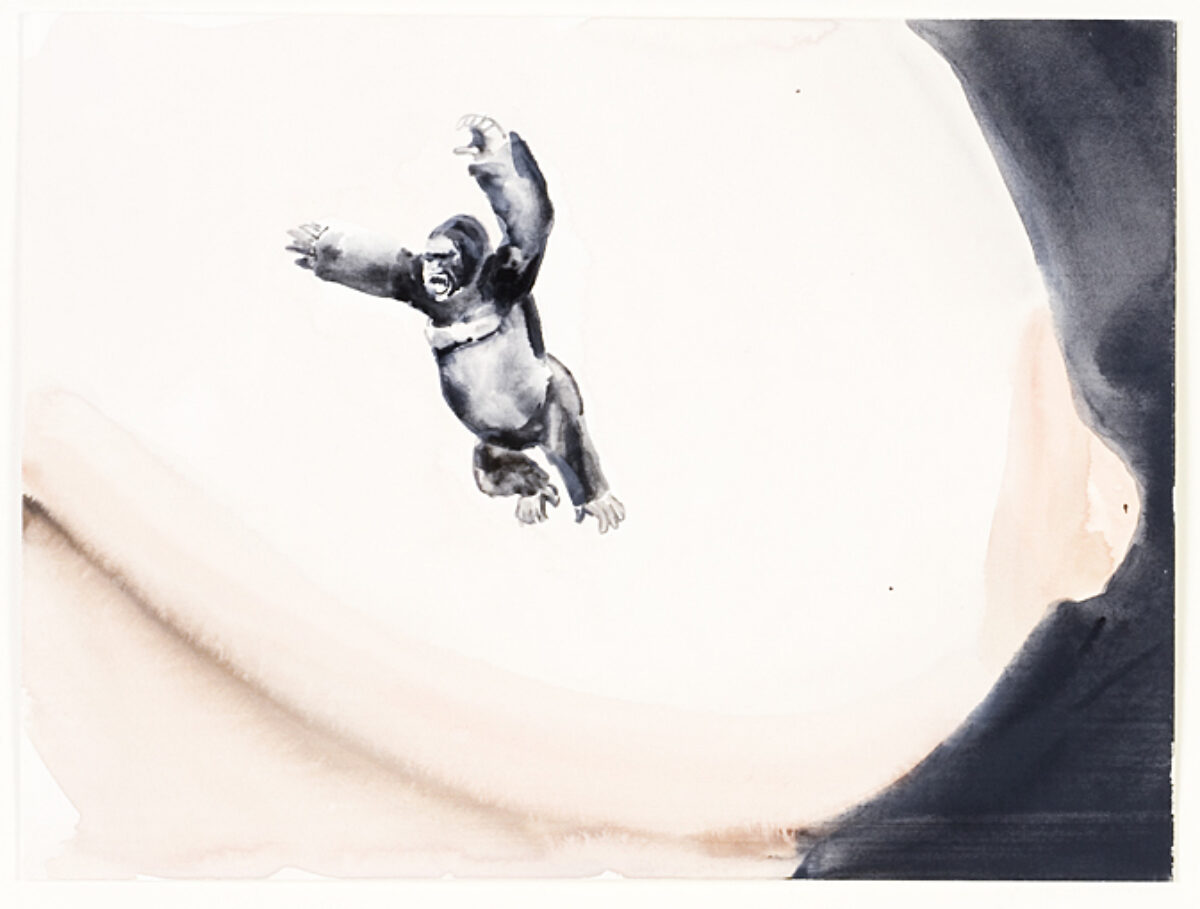

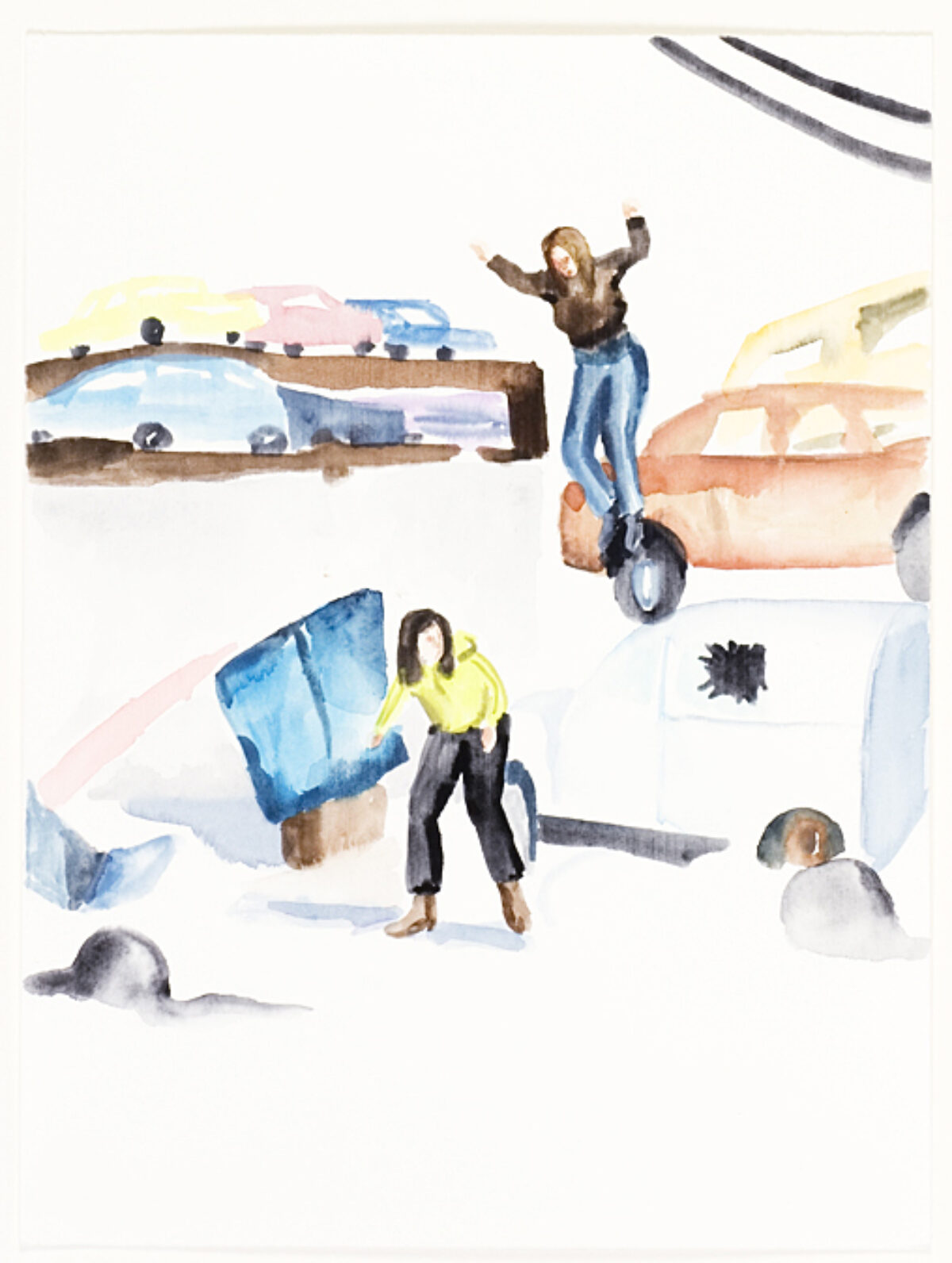

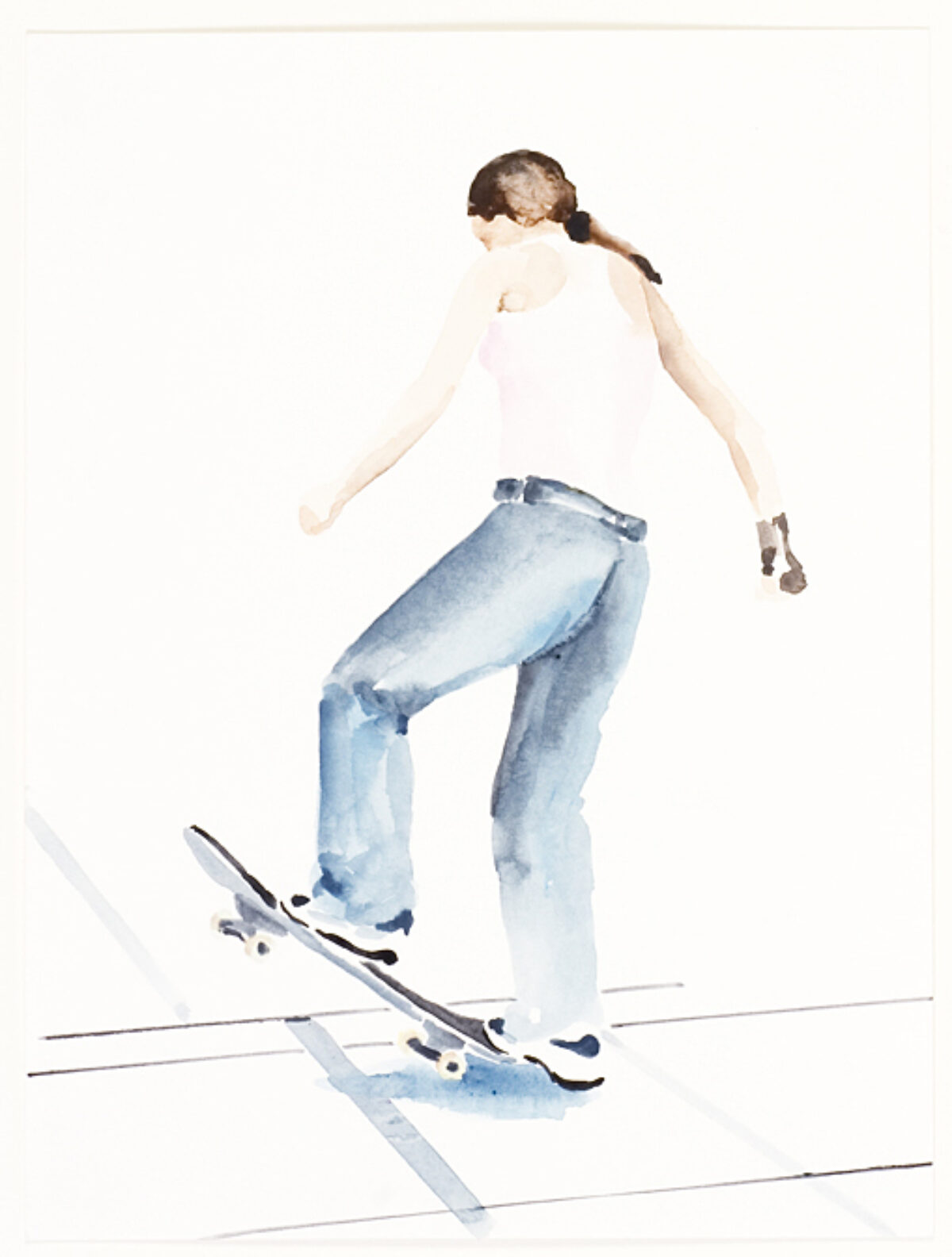

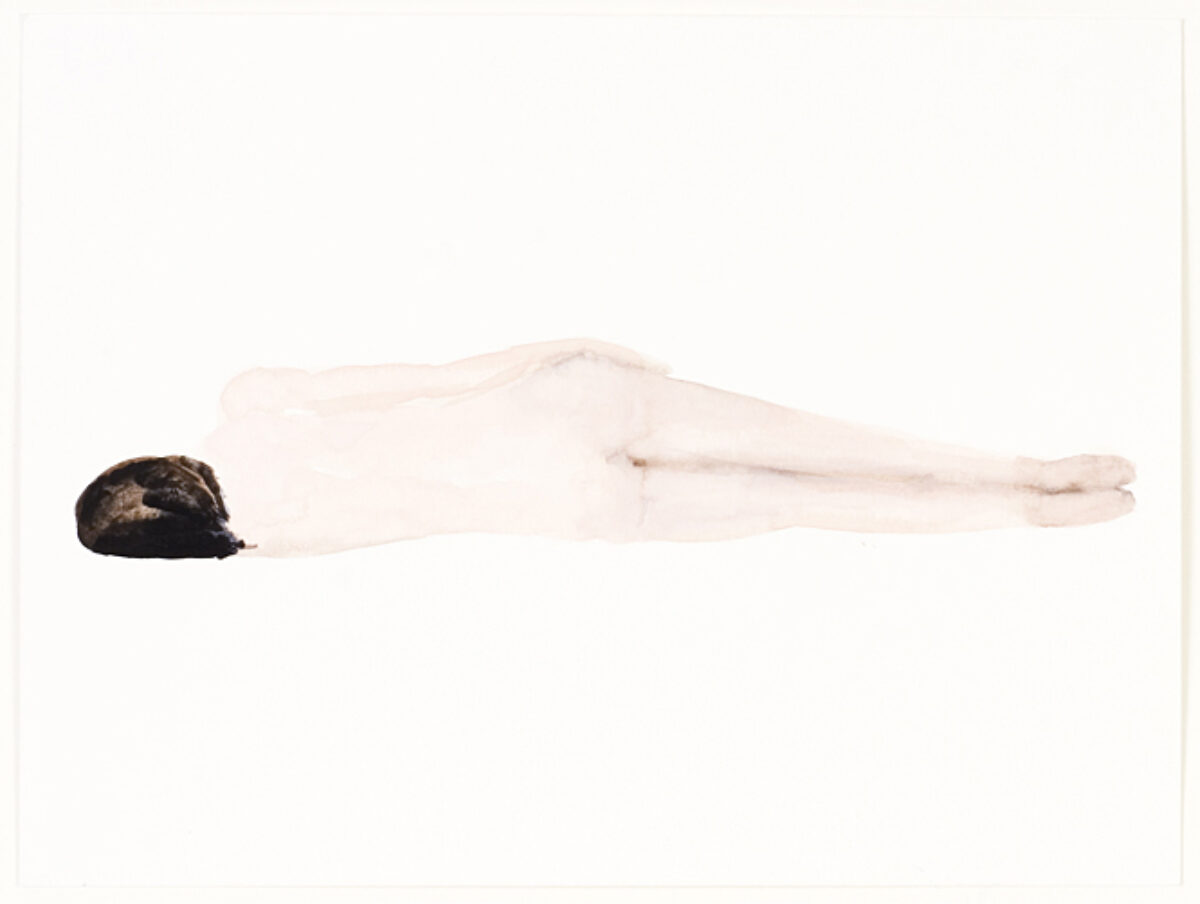

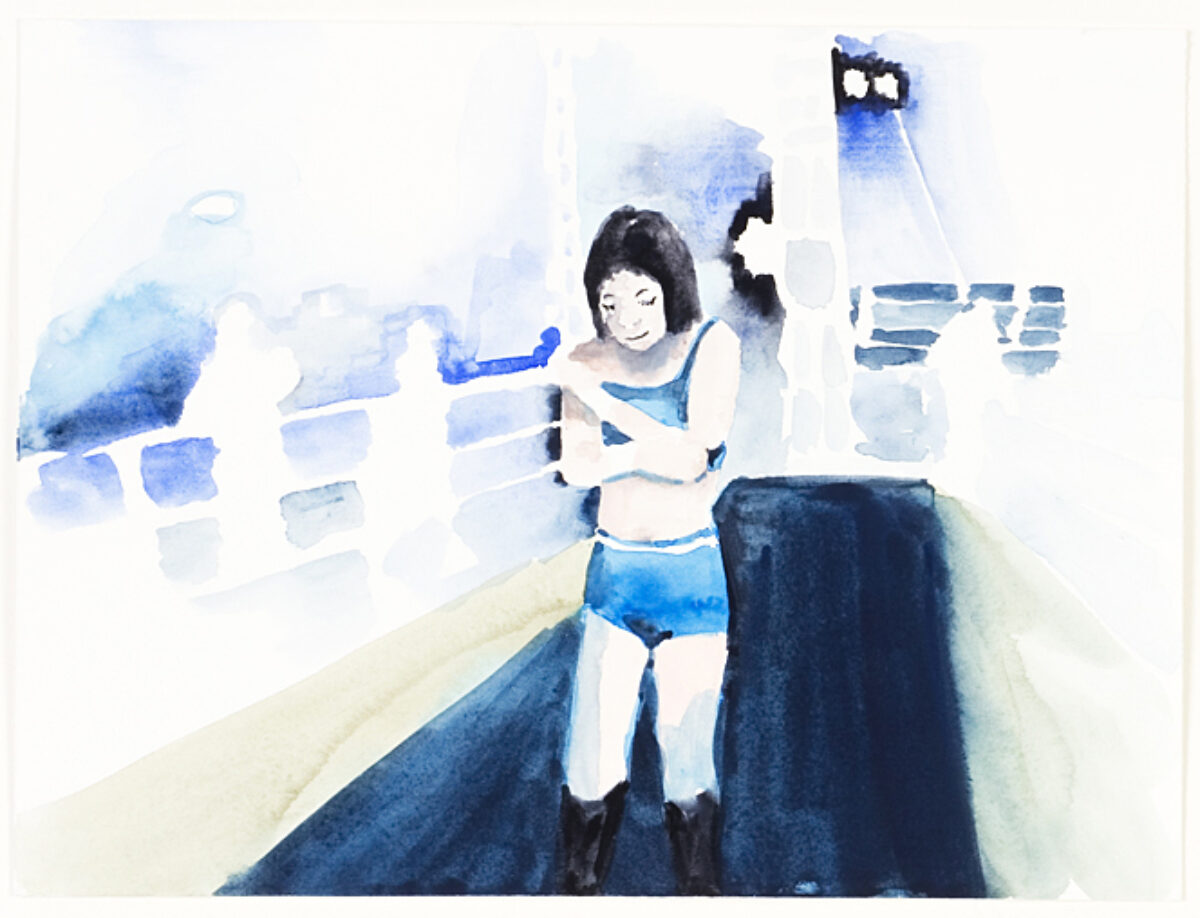

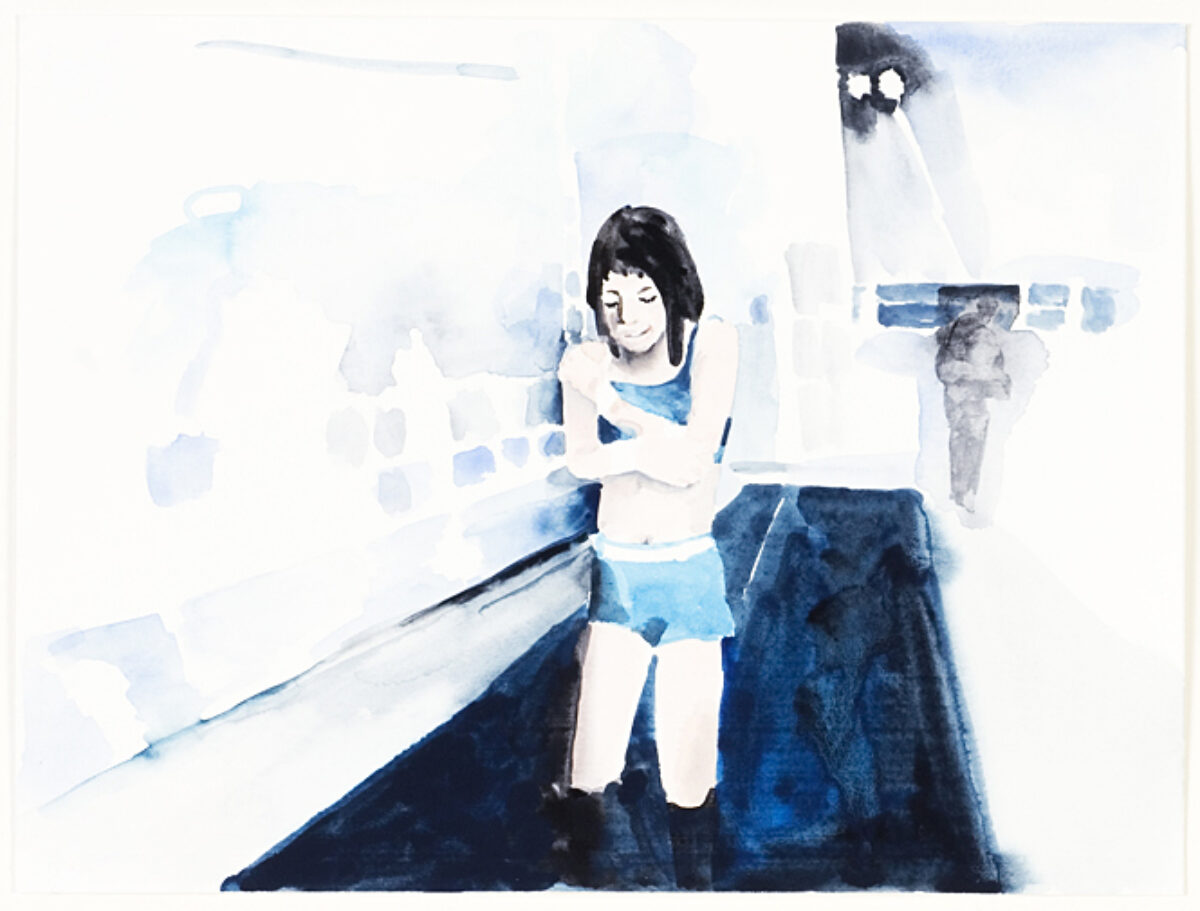

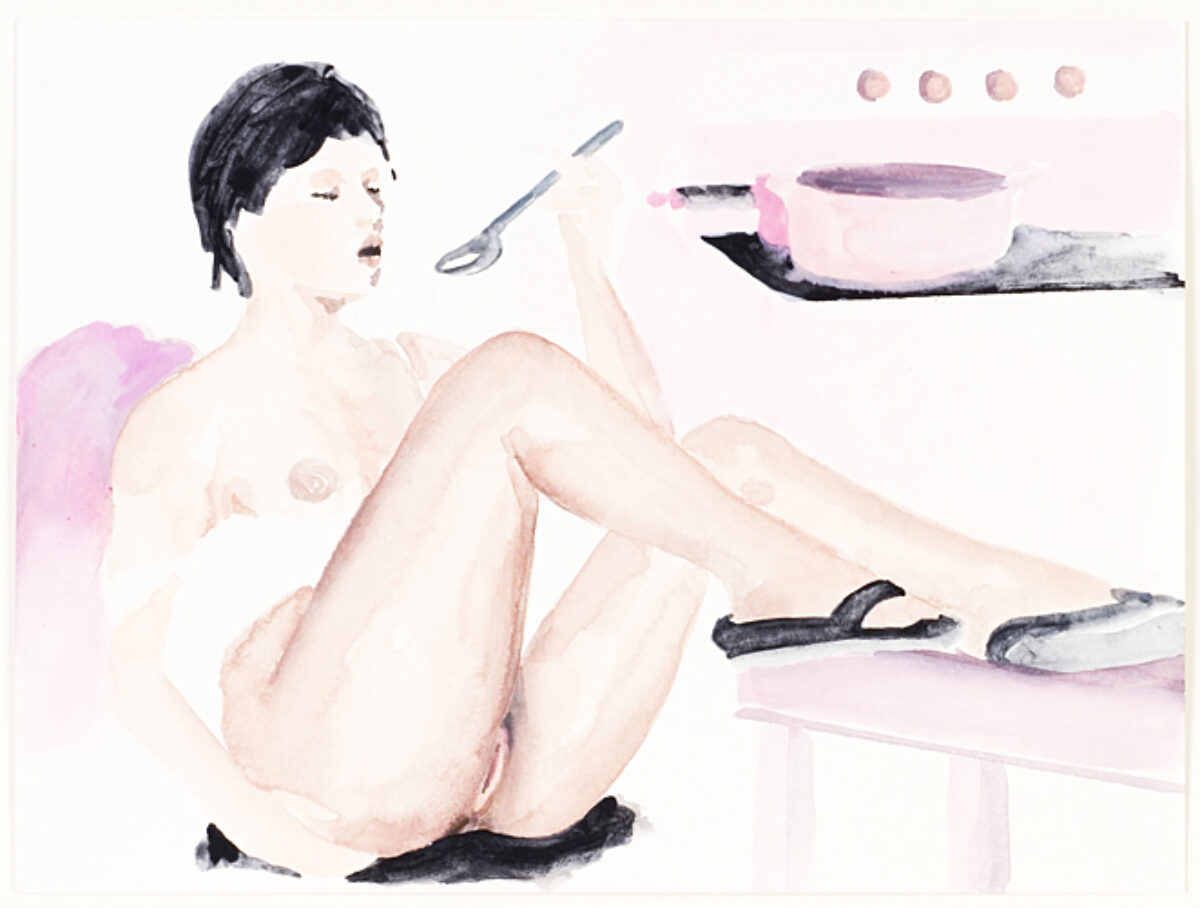

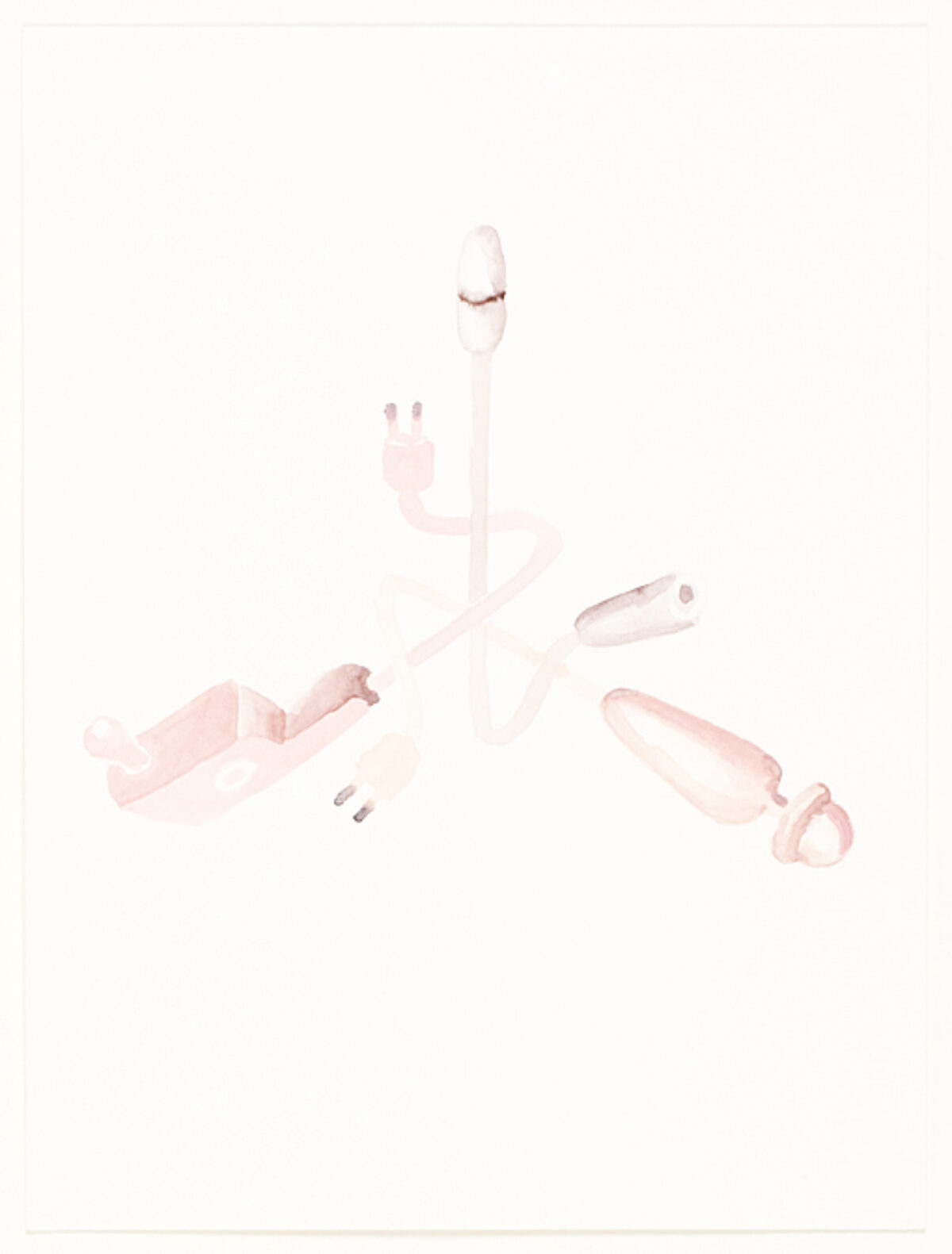

“I am interested in private space,” says Kerstin Drechsel. In this she is quite radical, for she even includes that most private of spaces —her own sex life. Drechsel is a lesbian, and her paintings show the naked bodies of her lovers and of lovemaking couples. She also depicts certain intimate acts such as urinating. Her aim, however, is not to provoke as much as it is to show how natural and matter-of-fact these acts are. Rarely has the female body been depicted so openly in European art—and yet her paintings are not vulgar, but feel light and radiant. D rechsel achieves this effect through a unique technique and the use of diverse materials. Her series Daily consists of hundreds of watercolors on A4-sized paper depicting everyday scenes from her life, her feelings, and her fantasies. Although she paints with oil on canvas, she dilutes the paints so much that they look like watercolors. The overwhelmingly light, almost transparent colors cause the pictures to look as if they are saturated with light, and remind us of Impressionist paintings. As a result, although Drechsel tends to depict raw themes, her paintings possess an almost romantic aura. In Heat Country is a series of large-format black-and-white silkscreen prints on canvas in which Drechsel addresses stereotypical depictions of lesbian love from pornographic magazines (“baby, girl, good, slippy, mama”). She photographs hidden corners, rooms with beds, or bathrooms—places she finds at her friends’ homes—which she subsequently paints. But she chooses only certain places: the more underwear, toilet paper, crumpled facial tissue, and cosmetic tubes on the bed, the better. Lying amidst this “tumor of consumption” (Drechsel’s term for this pile of things) is a photograph or a pair of glasses. Not only garbage and everyday items are piled on the beds and sinks (or underneath them and behind them), but also a storehouse of reserve goods. And so this series of paintings bears the title Rezerve (Reserve). W e also encounter disorder and piles of objects in Drechsel’s series Unser Haus (Our House). One painting from the year 2005 shows a room filled to the brim with books and paper. But Drechsel in no way stages these scenes; they are the places of work of her acquaintances, members of Berlin’s cultural scene. She is fascinated by the intensity with which work is mixed with private life. The private sphere is transformed into a disorderly and chaotic accumulation of work-related material—in this case, books and paper.

Text by Noemi Smolik