Anna, born Helming in 1937 in Bork, Germany

Bernhard, born in 1937 in Dortmund, Germany

In contemporary art, perhaps no one transcends their small-town world. How could they. For one thing, both artists come from a deep-rooted small-town environment – but in contrast to the many others, they have no problem admitting it – and they also live in Germany. Germany is known for cultivating its own form of small-town life that is a combination of two contradictory world views: a tersely rational approach formulated by German philosophers and strong irrationality. As the last century has shown, this leads to conflicts that could have catastrophic consequences.

Anna and Bernhard Blume willingly confront this conflict in their work. Their world, which they mainly create in front of a black-and-white camera, illustrates the German suburbanite’s attempt to cope with its irrational fears, instincts and fantasies, and at the same time not to betray the sublime rationality, as the leading German philosophers had urged. The result is always the same: chaos, corruption, and catastrophe.

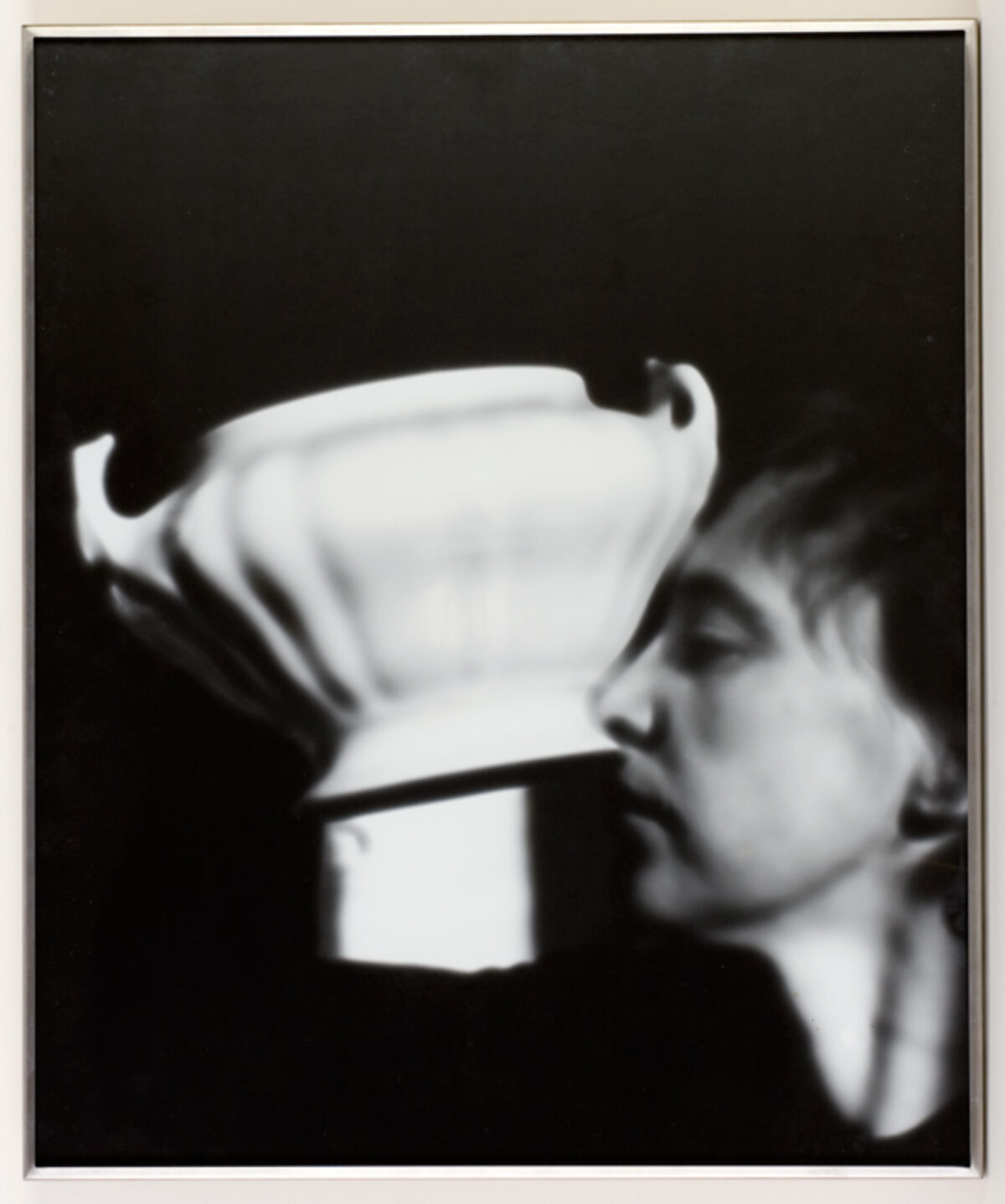

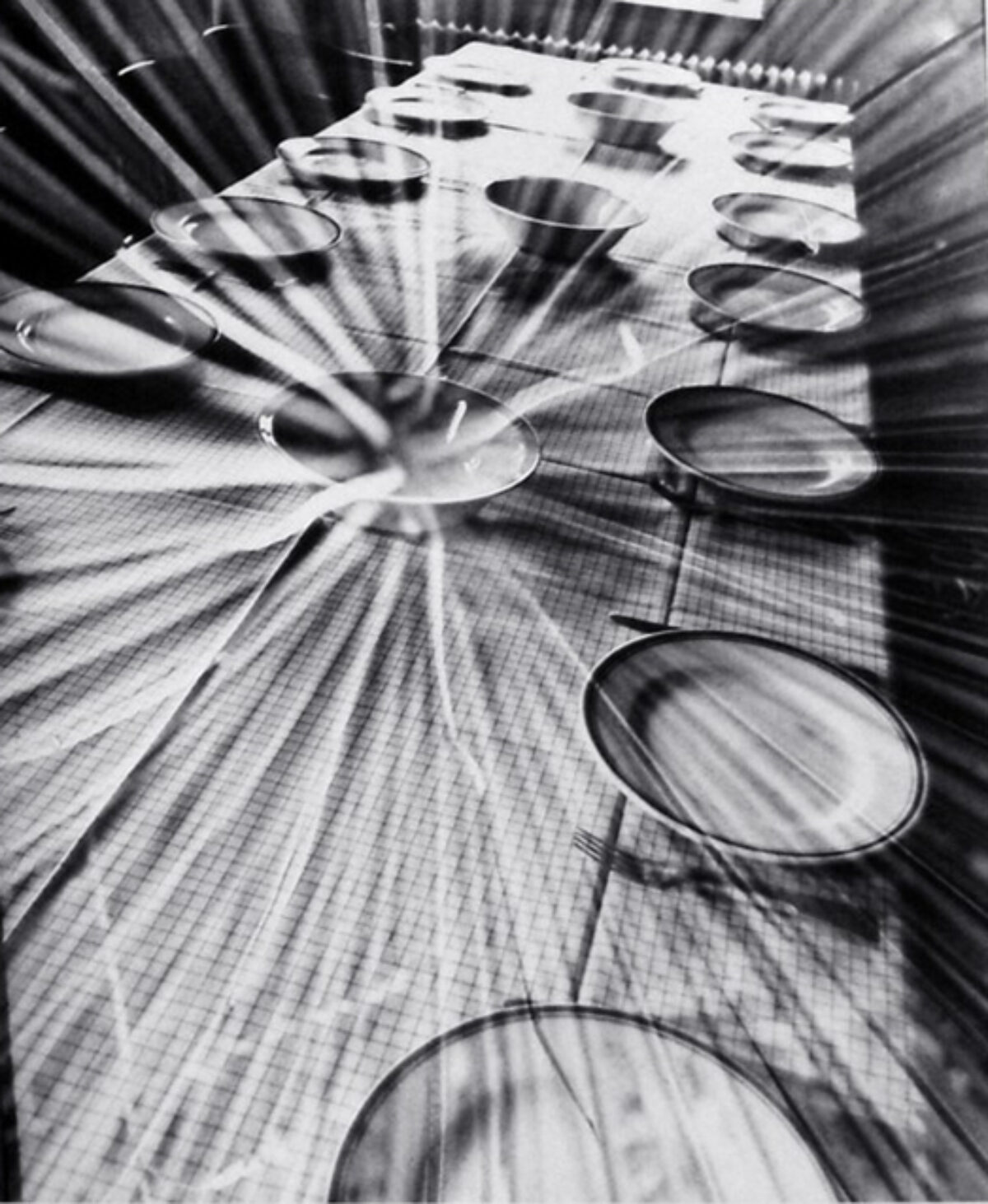

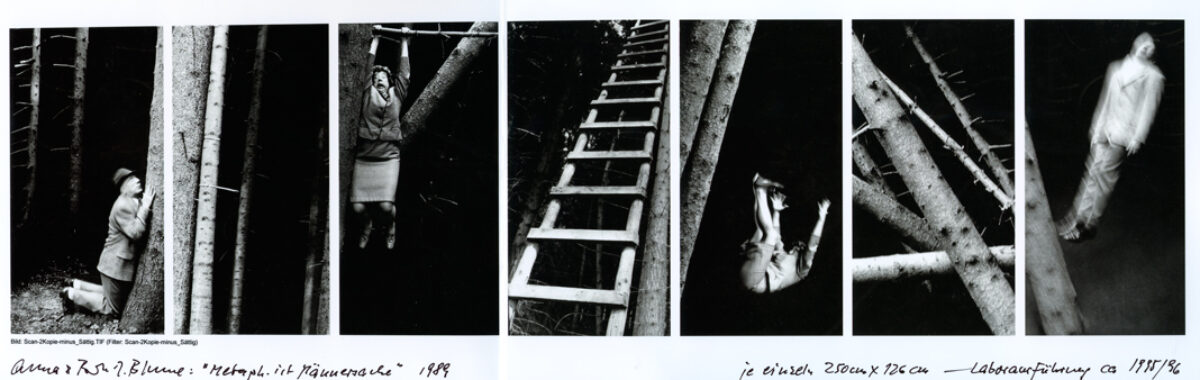

Their photo sequence from 1989, “Methaphysik ist Männersache” (Metaphysics is man’s work) is unforgettable. In the deep German forest, associated with the great philosopher Martin Heidegger, unbelievable things are taking place. Trees begin to move, women hang like rags on the branches, and so the male saviour had no choice but to imploringly kneel in front of the trunk of one of these many trees. In the “Eucharismus” (the Eucharist) from 1979, everyday lunch transforms into a religious ritual reminiscent of the last supper. In “Vasenekstasen” (Vase Ecstasy) from 1987, living room vases are set loose and surrealistically threaten the owners of the distastefully furnished living room. Even the actors in this series, Anna and Bernhard, are dress with the same bad taste. She is in a flowered dress made of stiff, plastic material with curled hair. He is dressed in grey trousers, a white shirt with a chequered necktie, and a cheap imitation English jacket.

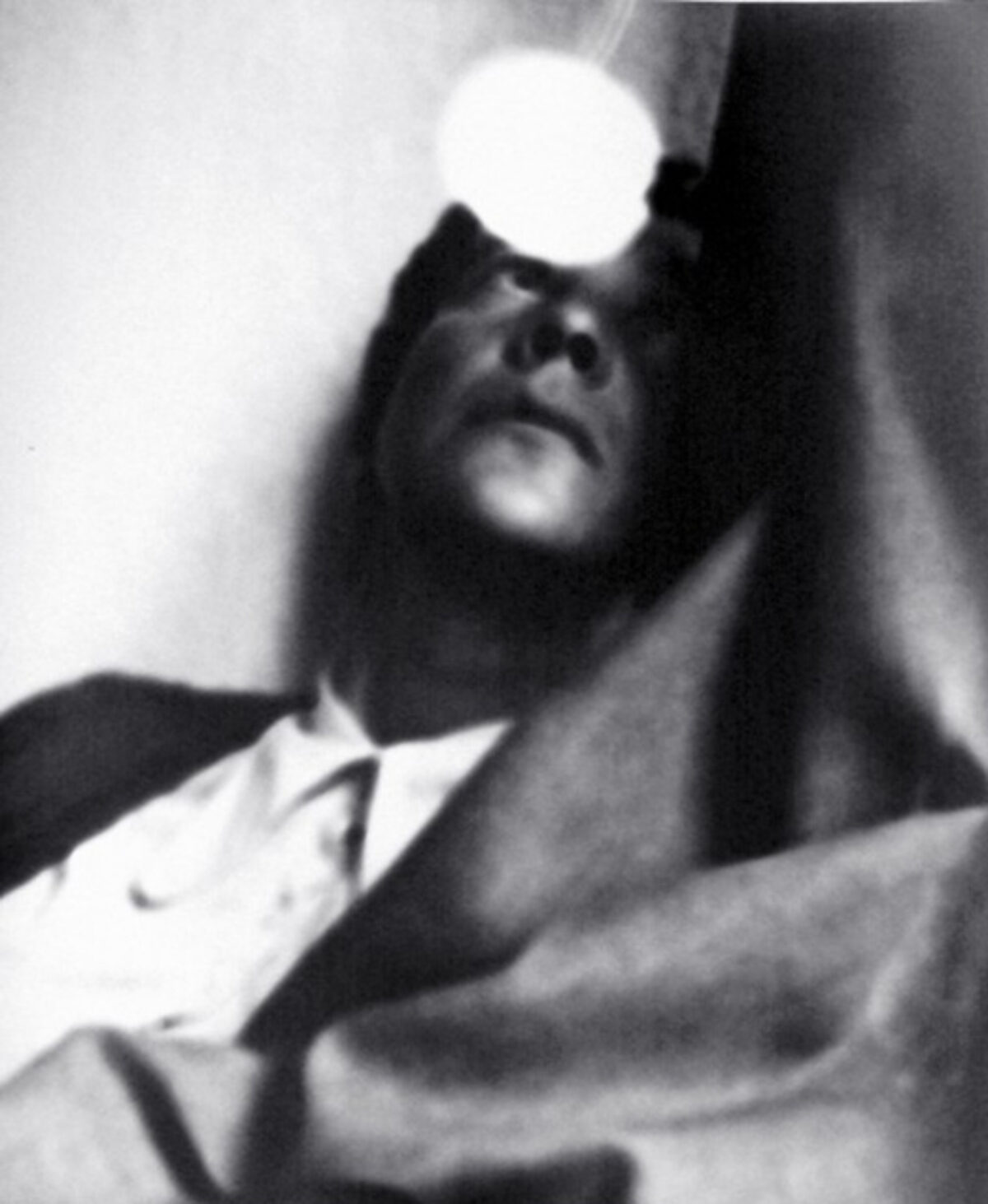

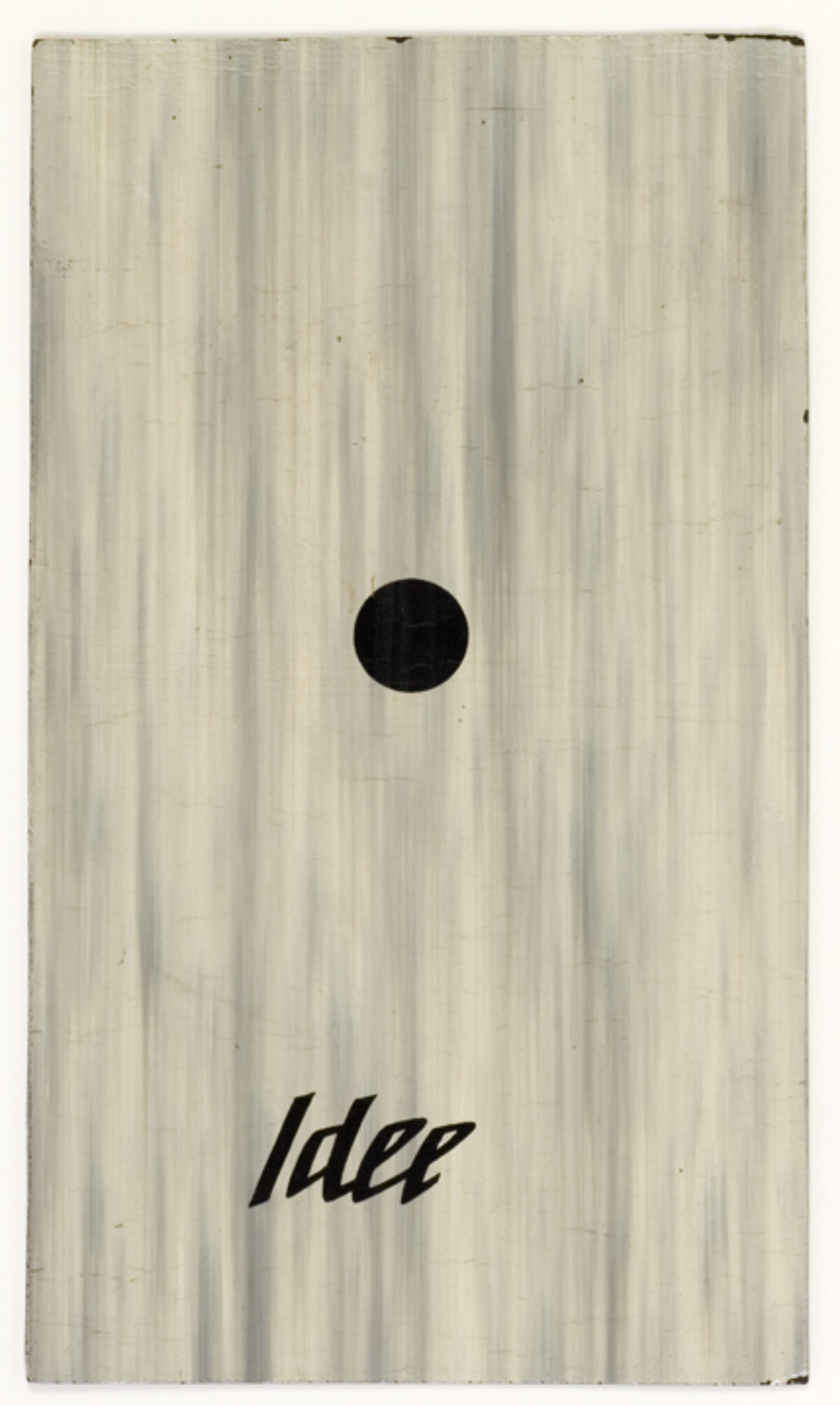

One of their last sequences is entitled “Tranzendentaler Konstruktivismus” (Transcendental Constructivism). Constructivism, an artistic movement from the beginning of the last century, asserts a rationality that is defined with the help of pure geometric shapes. However, how do these shapes allow for the needs of the human body whose shapes work against any geometric order? And how can rational understanding of the world be transcendental? One of the shots from this sequence gives a clear answer: it shows a face pressed between two square surfaces radiating eternal suffering.

Text by Noemi Smolik