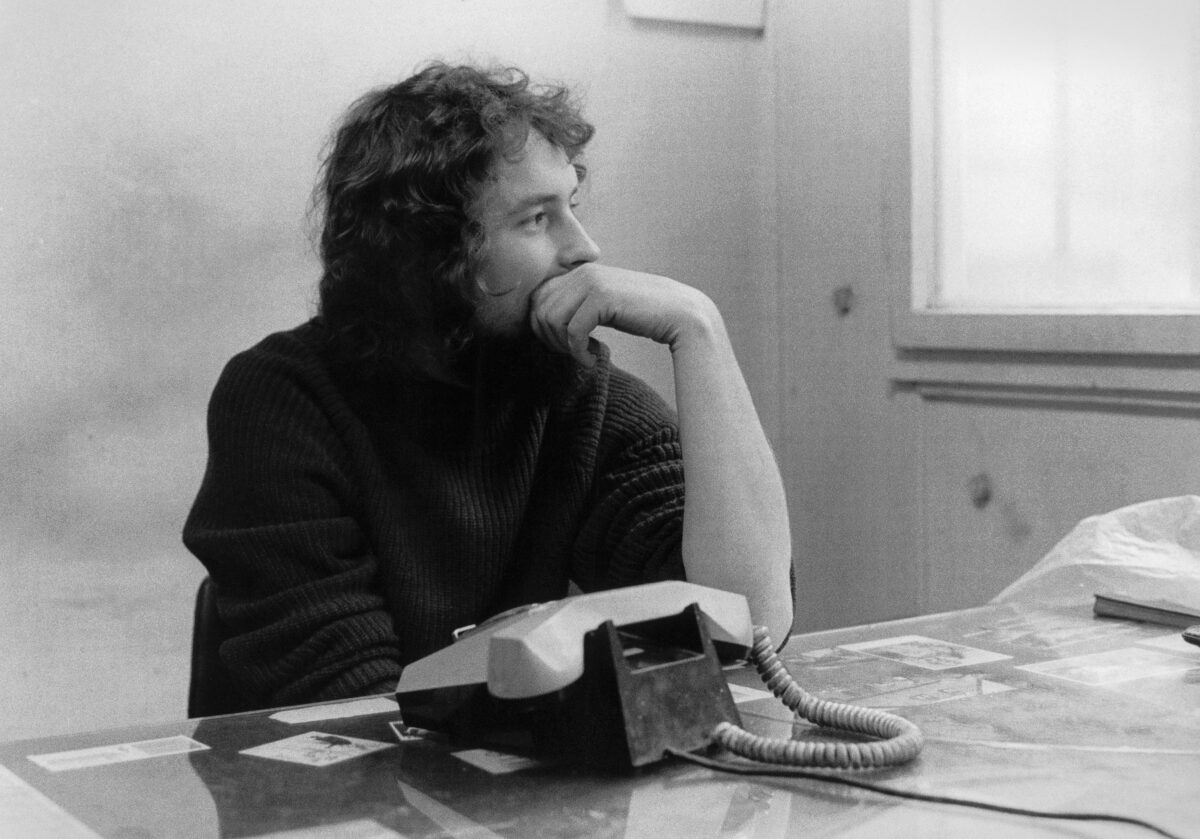

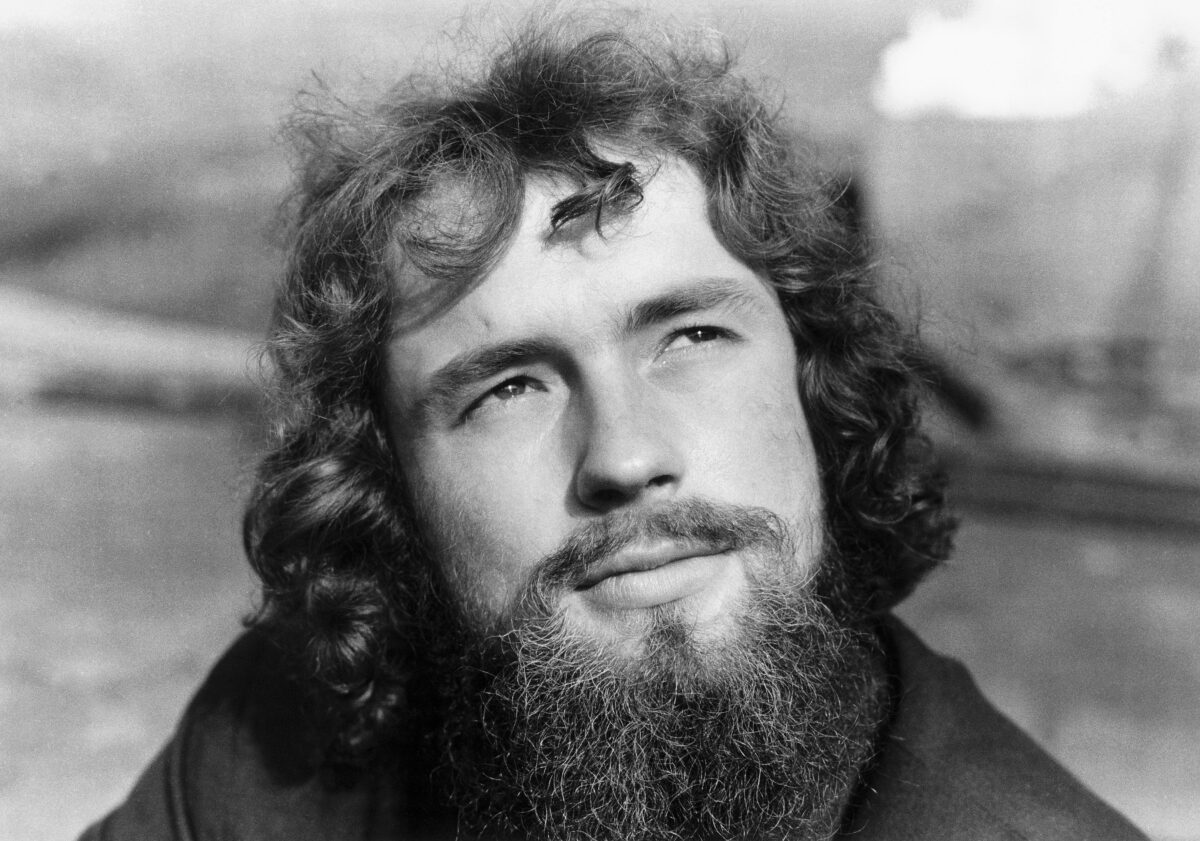

Born 1953 in Prague, Czech Republic, also residing in Prague

On 11 May 1976, Kovanda asked a man and a woman to stand bare-foot and kiss on wet cement. This act, “The Kiss”, is then documented by the photo-portraits of the participants and the footprints left in the hardened cement. The kiss itself is not seen, though it is still present: in the audience’s imagination. This occurred in Prague, during the communist regime, during which time suspicion and fear prevented any form of open meeting. Nevertheless, a kiss is a gesture of unconditional love. And indeed the philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas considers love as a completely unique form of meeting, because it provides strength to free oneself from the bonds of power.

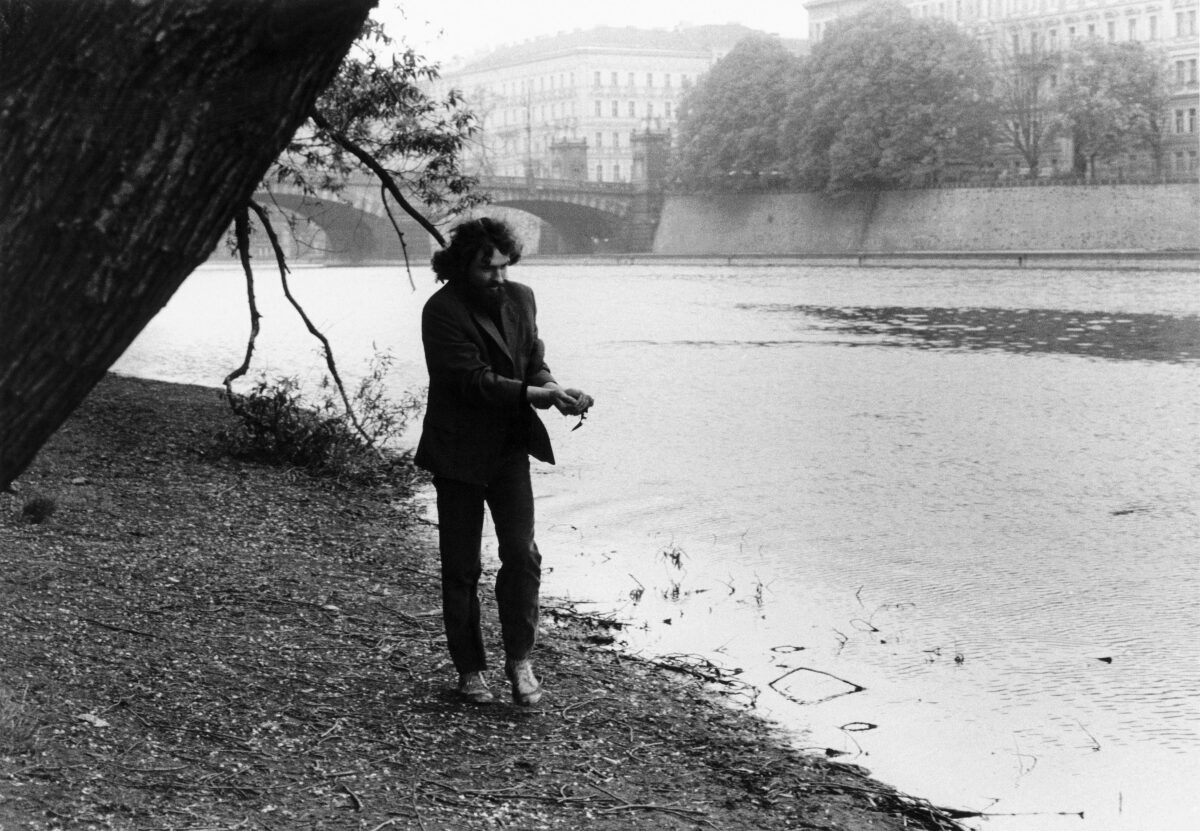

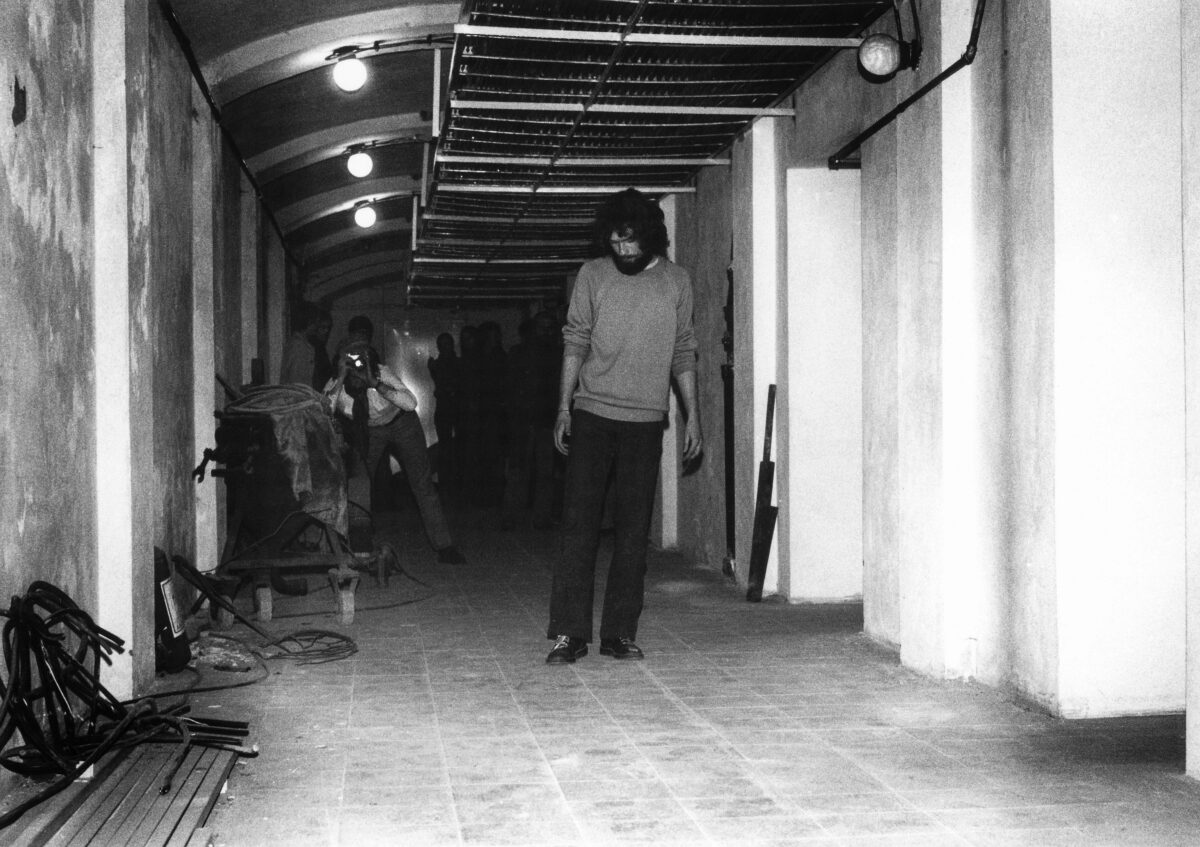

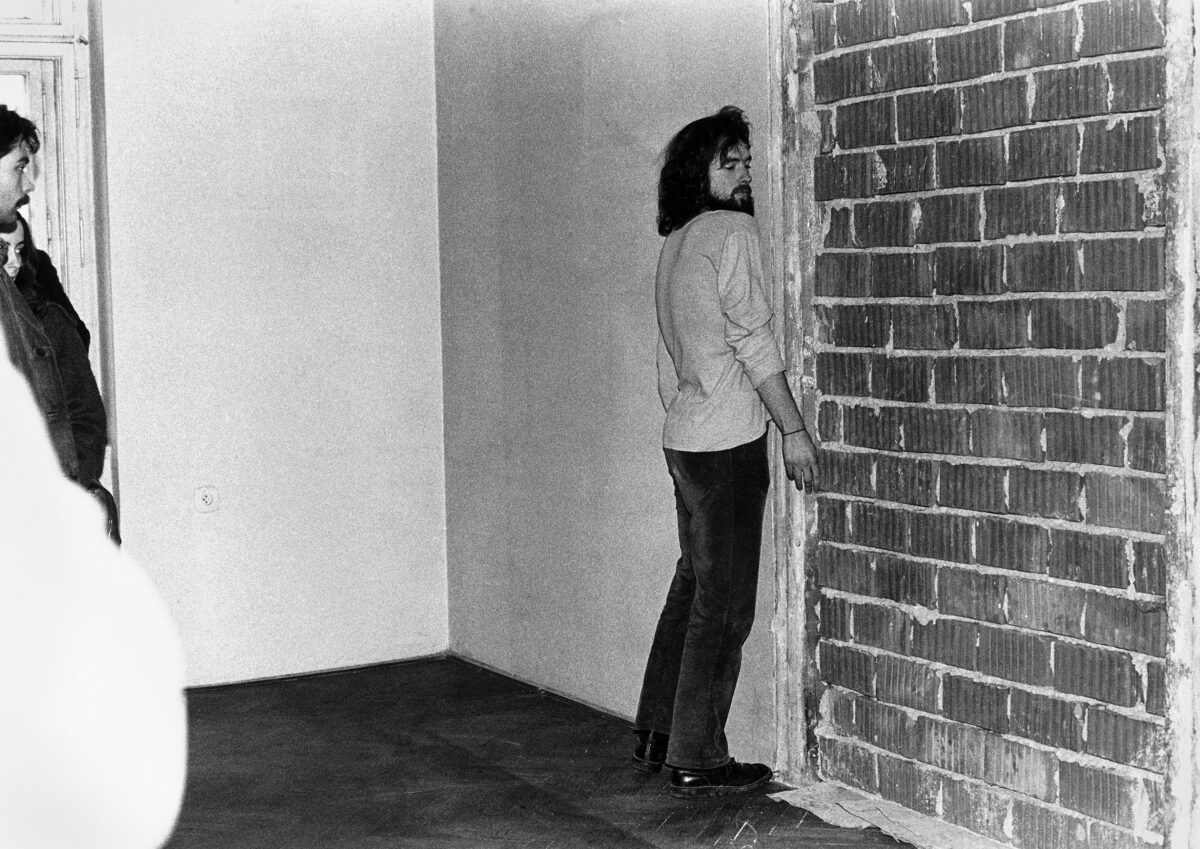

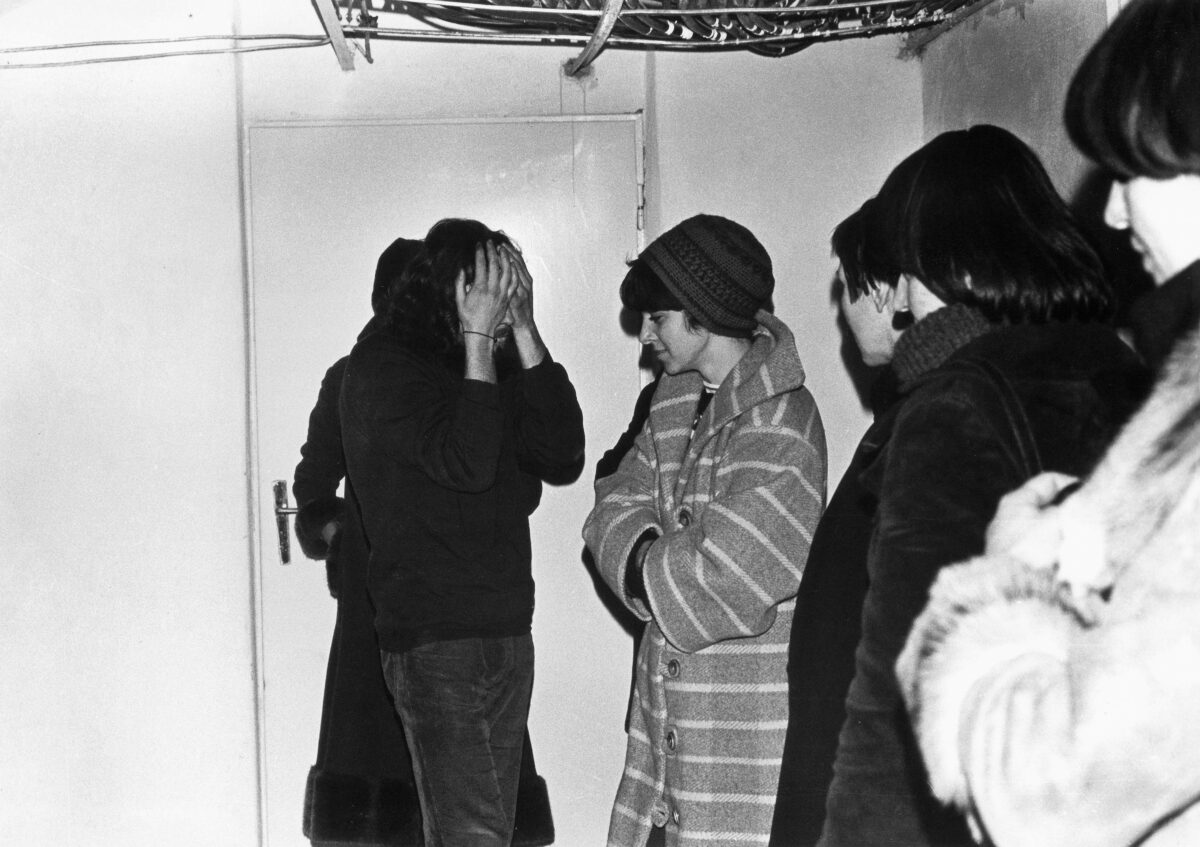

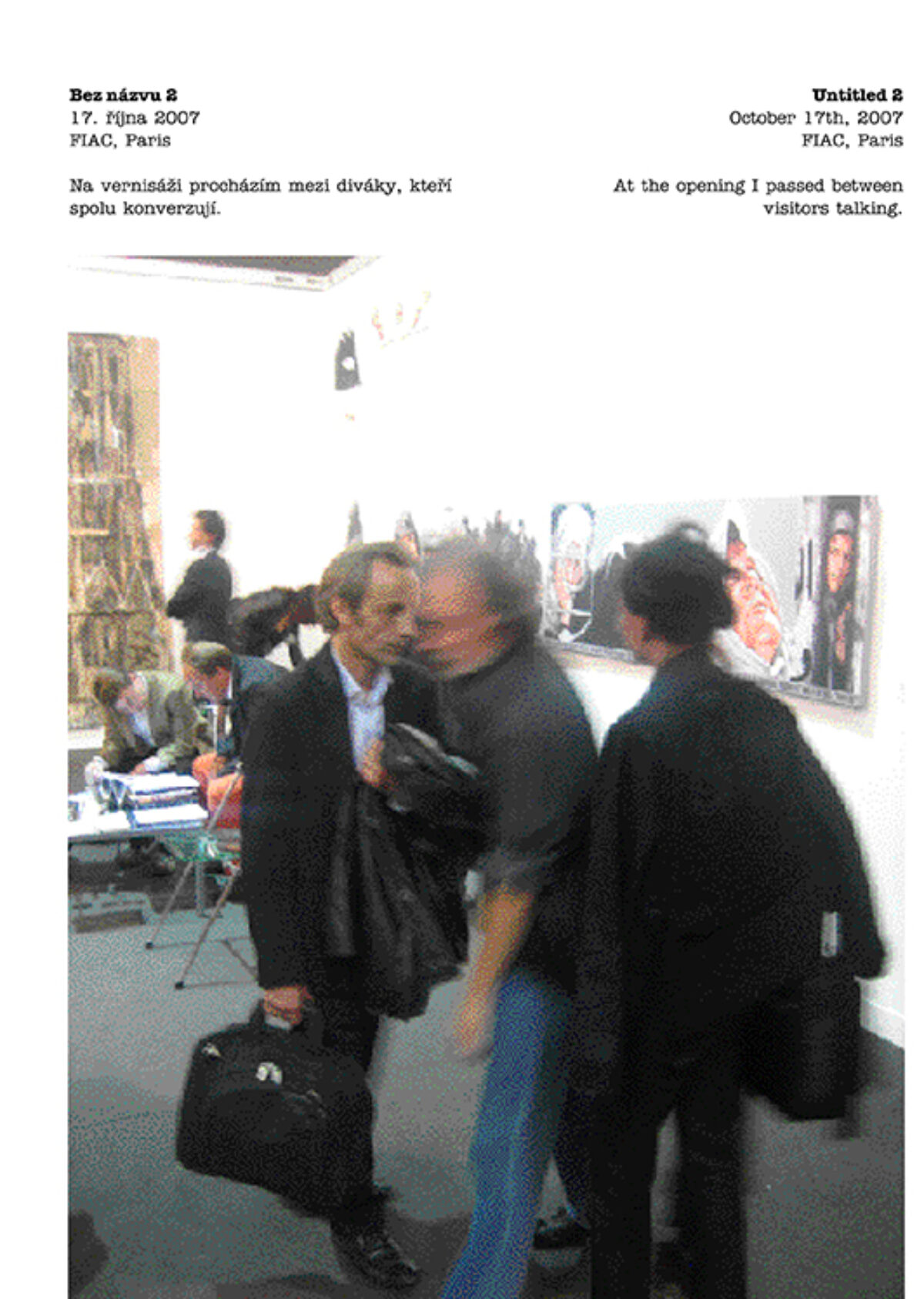

In later years, Kovanda continues in a similar spirit, with acts – now well-known – that he carefully documents each time, as if they involved a scientific experiment. Once, waiting by a railing on Wenceslas Square, another time, standing with out-stretched arms in the middle of a moving crowd, or carrying water from the Vltava River in his hands against the current. Whatever these acts might be, they all have one thing in common: they are an expression of free agency.

Kovanda’s acts are absurd. And the absurdity increases until it reaches the point of minimalism and conceptualism, e.g. when in 1981 he pours salt around a bridge pillar and sugar alongside the arched railing and calls it “Salty Corner, Sweet Arch”; but it also applies to his later works. His action at the Tate Modern Gallery in London in 2007 was also absurd, as if he was revisiting his earlier “The Kiss”. This time, he himself stands behind a glass wall and with a sign on his chest asks by-passers to kiss him. And indeed – the photos of girls kissing the artist through glass then went around the world.

Baruch Spinoza, a frequently cited philosopher from the 17th century, believed that every free notion is first an act of conscious deception. And what else are Kovanda’s acts than deception and pretending? They can be instructions for achieving the impossible: how to break into the political or artistic constructs of rigid totalitarian thinking with a hole that can be filled with free will. The fact that these instructions seem absurd does not make them any less effective. Or, as Franz Kafka already knew, realities constructed from arbitrariness, coincidences, and force cannot be rationally resisted. They can be resisted only with an illusion based on the ability to imagine the impossible, and especially the courage to deal with the absurd.

Text by Noemi Smolik