Dammann, Martin

Born 1965 in Friedrichshafen, Germany, lives in Berlin

“There is no true life within a wrong one.”

Martin Dammann shows carefree moments on historical photographs from the First and Second World War. The protagonists are soldiers who are taking a timeout from the harsh reality of killing and being killed by dressing up—quite often as women. A severe march becomes a jolly round, swinging legs lifting the skirts. The soldier shows his human side.

The sight of such gaiety “underneath the swastika” may send a chill down the contemporary viewer’s spine. Adorno’s statement about fascism in Europe, written in exile in America, appears at the very least as a question in our heads. We are too much reminded of photographs of prisoners on leashes at Abu Ghraib; colonialist denigration of “Indians” and the “Orient” has become the subject of criticism. War and soldiers lost their innocence long ago. At least in Europe they are no longer associated with pride and honor. Instead, armed conflict is seen as a never-ending evil. Dammann’s pictures of carnival-like games present us with a moral dilemma. Festivities have always been a necessary escape from the daily routine, especially from an unjust and miserable world. By comparison, the association of war and fun in this collection of photographs presents us with a by today’s standards nearly unbearable cynicism.

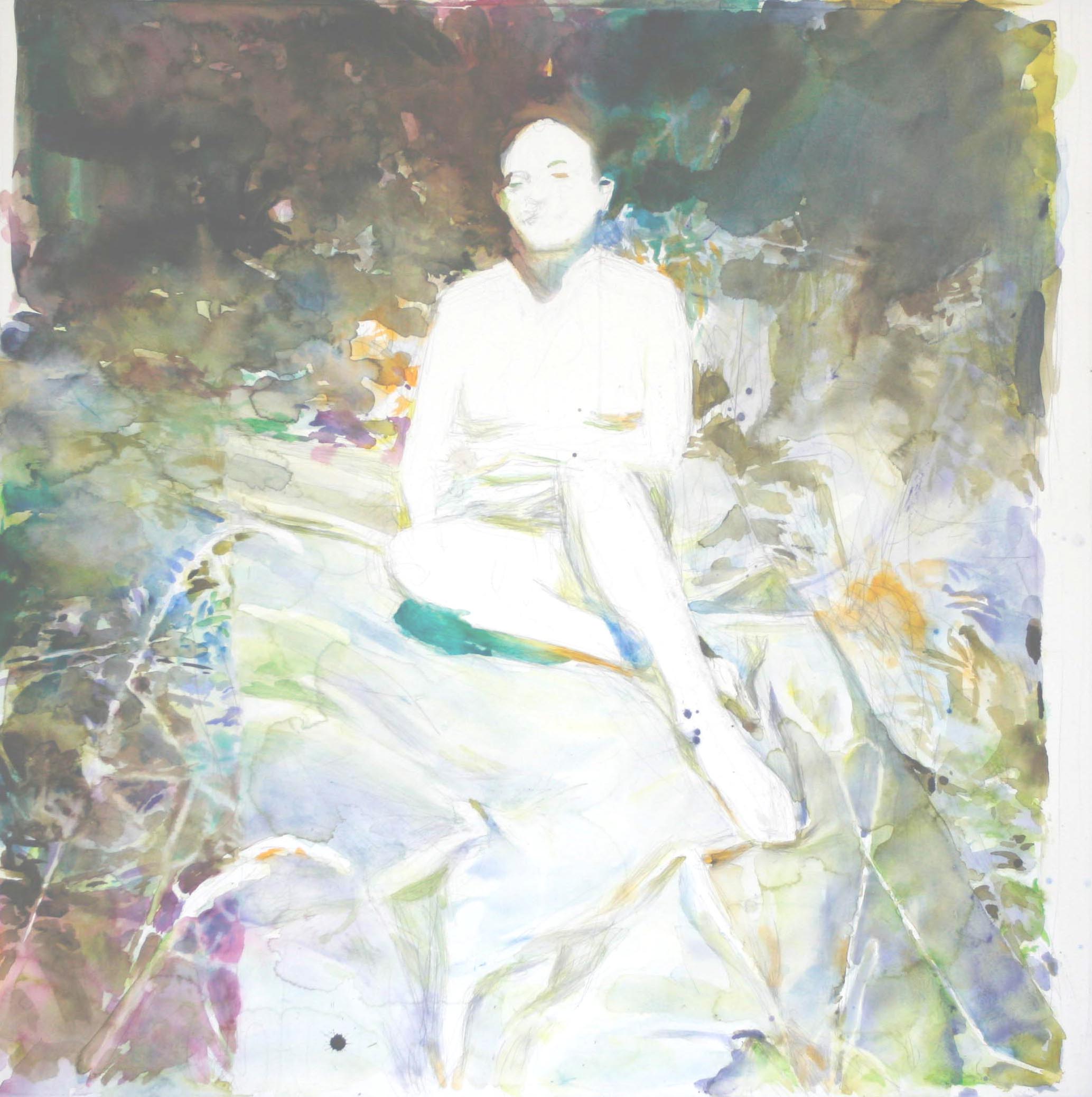

This ambivalence of Dammann’s works is further exacerbated when he paints over the archival photographs from London’s Archive of Modern Conflict in bright watercolors —a harmless, nearly naive painting technique that not only contrasts sharply to the size of many of the works (which are as large as history paintings made in oil), but also builds up a dangerous tension between the figures’ reverie and their uniforms. The dreamlike scenery of a colorful landscape becomes a backdrop for an anticipated nightmare. In some of his watercolors, Dammann lets the colors run until the subject is nearly unidentifiable. The photograph’s import is lost in images resembling and at the same time evoking vague snapshots. Dammann explores each medium’s particular form of communication. He questions the relationship between as well as the changing interaction of media and truth.