Prince, Richard

Born 1949, Panama Canal Zone, lives in New York

In the late 1970s, when Richard Prince began to “rephotograph” his photographs of adver tisements from magazines and newspapers, nobody knew how to respond.

There are pens, watches, and living rooms in these photographs, banal subject matter,

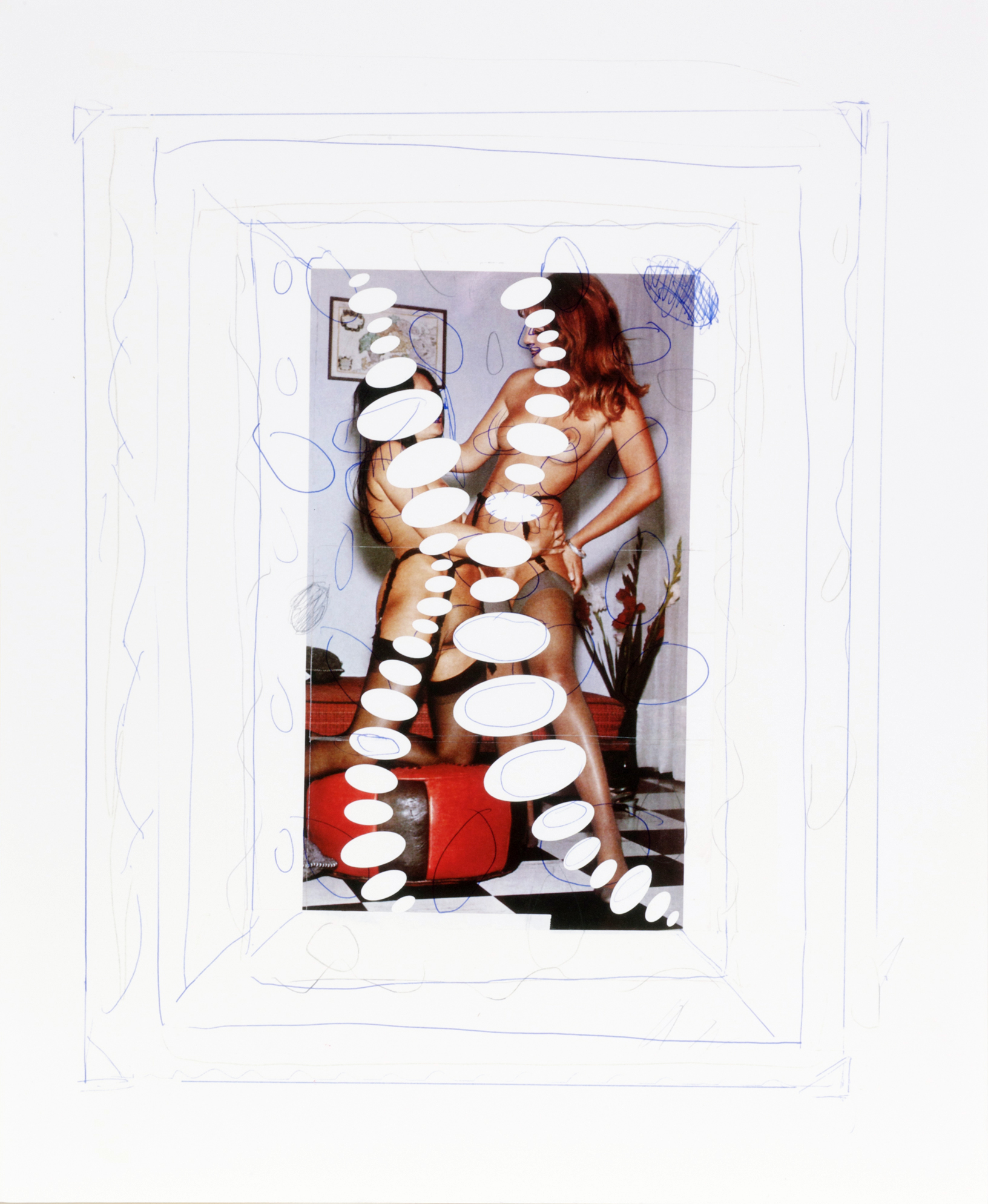

the faces of attractive women, but no celebrities as in the snapshots of Andy Warhol. Prince became famous in the 1980s for his Cowboys, which showed heroiclooking men from the American “Wild West” holding lassoes and riding horses, taken from the ubiquitous Marl boro cigarette advertisements. For Girlfriends, another wellknown series, Prince was inspired by biker magazines and their almost ritual motif of linking motorcycles, the object of desire, with sexy women. He uses amateur snapshots for the background of these “rephotographed” photographs which were sent to these maga zines for publication. The beloved motorcycle is paired with the beloved girlfriend, who seems to be almost unaware of her own eroticism. Scantily clad, she poses in front of the freshly waxed motorcycle, sits on it, or sometimes even lies across it. She seems to be both inti mate and innocent.

Why does Prince choose these images? Together with Cindy Sherman and Louise Lawler, Prince belongs to the first generation of artists who grew up surrounded by technologi cally reproduced pictures. During their child hood, they encountered not only the images spread across the pages of comic books and glossy magazines, but also those emanating from the new medium of television, which had entered their living rooms, bringing with it a whole new world that began to permeate the old one little by little. Having a TV in the living room “was formative for us children,” says Prince in an interview. “It was the atmosphere in which we grew up. That’s why we thought: Sure, we are only kids, but we like this vibrant world more than the real one.”

Images are everywhere. They glow on screens, they shine on the pages of magazines. Prince’s generation lives and dreams of these images, without asking if they are real or not. These are photographs. As Prince says, photo graphs have the ability to seem real and to be trusted. Something from that naive child’s fascination with photographic images remains in his own work. This is not coincidental. Prince readily admits this, knowing that where there is fascination, there is also resistance. It is precisely this conflict, this ambivalence that characterizes his “rephotographed” works, as well as his later painted jokes. We laugh, but we are not truly cheerful.