Wulffen, Amelie

Born 1966 in Breitenbrunn, Germany, lives in Berlin

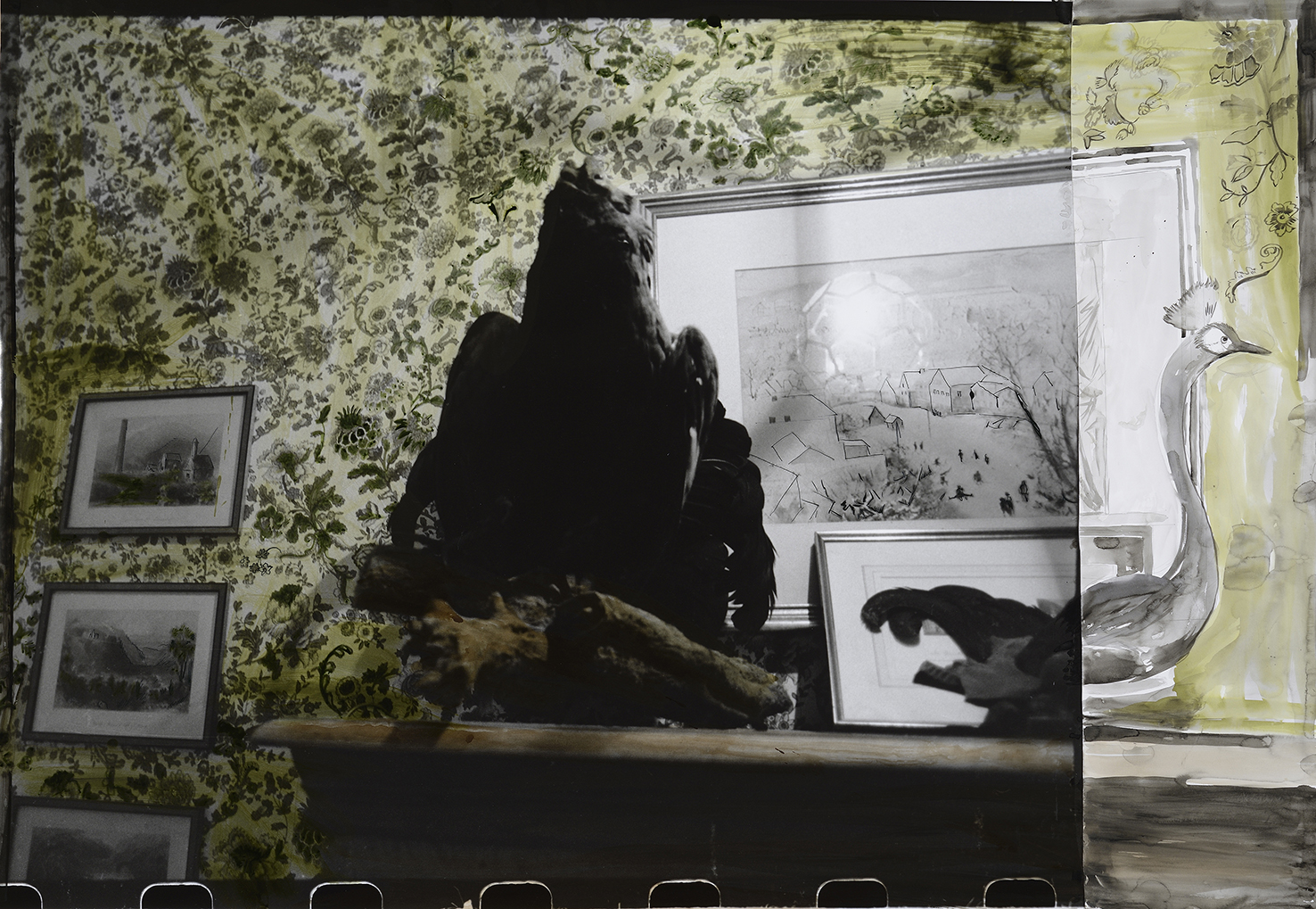

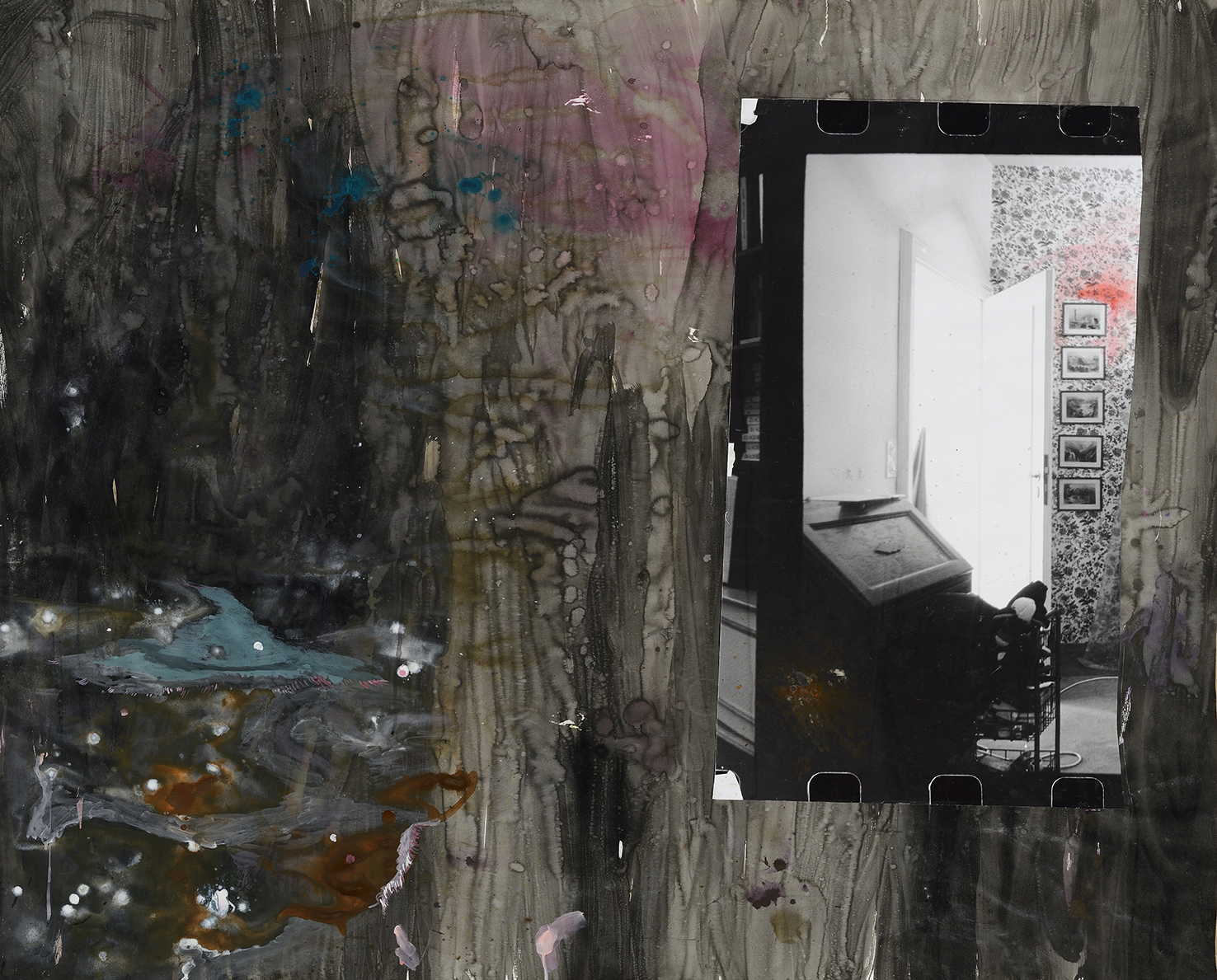

Amelie von Wulffen’s paintings are like memories: blurred, foggy, disappearing and reappearing, intangible and overexposed, sometimes even covered in dirt. Their subject matter floats in an indefinable space and time. In fact, they are not even true paintings; for the most part, they are giant painted-on black-and-white photographs, pasted over with different photographs and various cutouts from books and newspapers. At exhibitions, this process of “painting” often leaves the confines of the pictures and continues on the adjoining walls, panels, furniture, or benches. Drawing, painting, and photo-collage thus form one whole that sometimes takes on the nature of installation. This kind of combination is typical of the work of one of the most successful women painters of her generation.

Amelie von Wulffen often paints pictures within a picture, sometimes in several mutually overlapping layers. Her favorite subject is urban architecture, especially functionalism. Set against an immense black-and-white photograph of a geometrically segmented building complex from the 1930s, the towers of a surreal architecture rise into space, creating something between science fiction and the old-fashioned world of Hollywood B movies. Another recurring subject is interiors with Empire-style furniture, especially bedrooms with large beds, mirrors, paintings in heavy frames, and drapery with lavish folds. Von Wulffen populates these interiors with mysterious beings with long flowing hair, levitating as if in a trance and dressed in historical costumes. The viewer’s gaze is drawn to their faces; their large eyes stare into emptiness and their bodies dissolve like steam.

Von Wulffen’s world is like one giant illusion. And this despite the fact that she occasionally uses rough layers of dirty colors that add to her paintings’ everyday and ordinary character. Despite these rough layers of paint, her collage paintings and drawings, spreading out over the walls of the exhibition space like vaporous mists, strike us as light, almost impressionist. But sometimes we encounter reality as well. For instance when—amidst the drapery and old furniture, the layers of paint and photographs—we suddenly discover the clear outlines of a familiar face or motif: John Travolta or the painter’s grandmother, scenes from the paintings of Albrecht Dürer, or even the Russian author Alexander Solzhenitsyn. They appear suddenly, like a memory. Or are memories illusions?