Stratil, Václav

Born 1950 in Olomouc, Czech Republic, lives in Brno

What function can art have in today’s world? And the role of the artist? A shepherd, prophet, teacher, seducer, ascetic, or saint? This question is present in all the works of Václav Stratil, although at first glance, they seem so diverse. So what function can art have today?

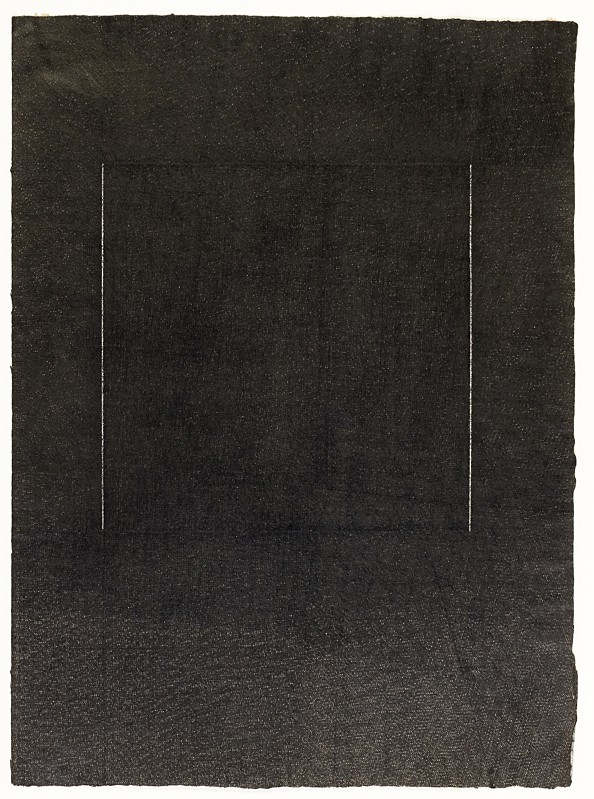

European art has its origins in Christian ritual—a constantly repeating sequence of acts whose purpose is to overcome fear and uncertainty. Every ritual also has a meditative dimension. In the 1980s, Stratil created ink-etched drawings. These large-format drawings (pp. 542–543) were created in a process that took long hours, resembling ritual acts. He cross-hatched as many as 20 layers of lines the length of rulers on huge paper that often covered the floor of the studio in which he also lived. Layer by layer, Stratil applied the black ink and covered everything, including the spots and stains of life. In such a way, he connected with the ancient function of art that involves ritual as well as meditative acts.

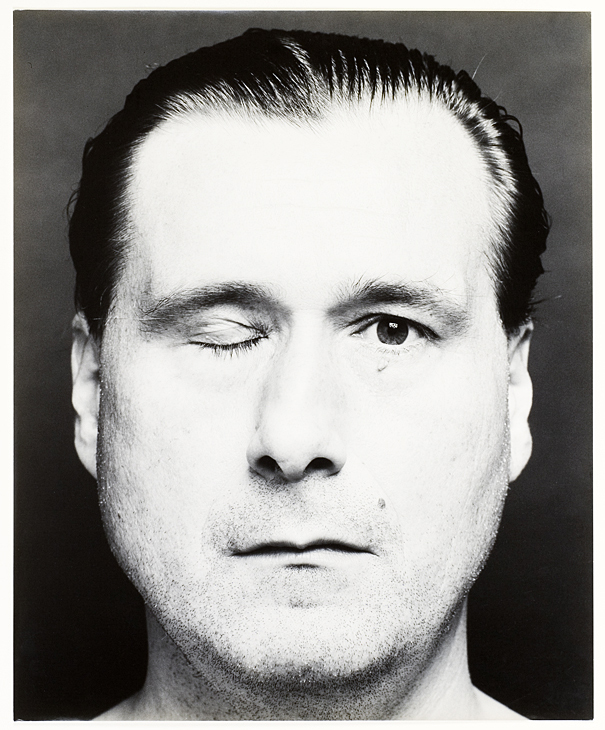

Since 1991, Stratil has had portraits made of himself at local photo studios. On these enlarged black-and-white photos with all their flaws, we typically see a frontal view of his face that is strongly illuminated. His gaze sometimes seems to be absent, sometimes as if he wanted to overwhelm his audience. One time, his expression is calm, another with twisted grimaces. He sometimes wears a hood resembling a monk’s frock, or as in paintings of early Christian saints, the images contain characteristic attributes, such as an egg or a spoon. Stratil’s self-portraits, more than 50 in total, radiate asceticism and the ability to suffer, expected from members of the religious orders—but not only that. We also feel resistance and patience—traits that are essential to all healing. Perhaps this is why Stratil called this series of portraits Monastic Patient. He connects it to another ancient notion of asceticism and suffering as an essential step towards healing and atonement. Not only the medieval altar convincingly illustrates that man was accompanied for hundreds of years on this journey by art. Even the origin of a work of art has been eternally connected with suffering and asceticism, and not only in the Christian tradition.

However, Stratil does not only see himself as an ascetic. From the titles of his exhibitions, containing photos as well as paintings, it is clear that he also considers himself a teacher or a good shepherd. It is all understood with exaggeration, as this unique artist also has a refreshing sense of humour.