Schamp, Matthias

Born 1964 in Krefeld, Germany, lives in Bochum

Matthias Schamp is an earnest jokester. His humorous, absurd and seemingly nonsense actions hide a cultural and political engagement and philosophical-conceptual approach. In 2010—“at the time when the blackberries are ripe”—he invited the citizens of Bochum to the “1st Bochum Lot Invasion” via a leaflet that was stylistically based on political flyers. The reason behind this action was a fence erected by the city that kept people from picking blackberries on an unused lot. The aim of this “radicalization of blueberry picking” was to “overcome [the fence] not only concretely, but abstractly as well”, Schamp wrote, citing Hegel: “…the Other of a limit is that which goes beyond it.” Another of Schamp’s actions aimed at overcoming limits was his Kunstwerke-Werfen (Artwork Throwing, 2011), by which Schamp and Stefan Schlichter opened the Situational Empty Lot Museum behind the fence. Several artists created works specifically for the first exhibition, but since the height of the fence makes the museum inaccessible, they were thrown over the fence onto the city-owned lot.

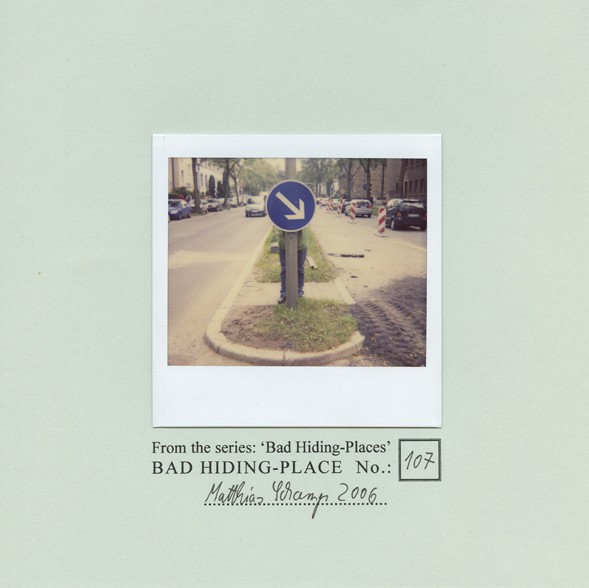

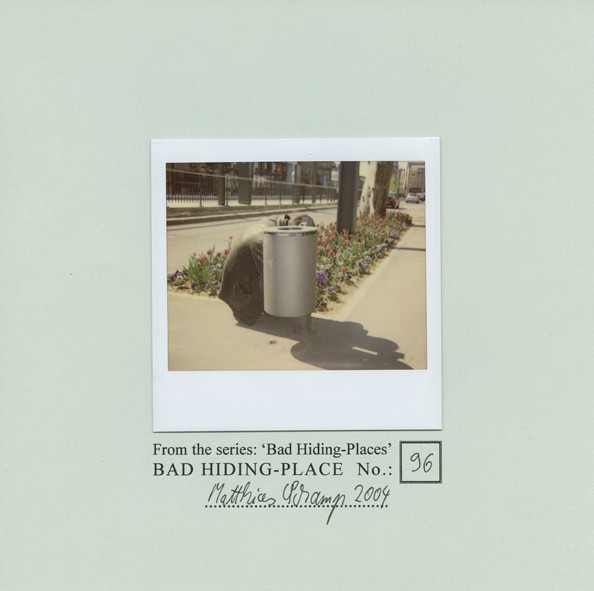

Schamp’s photographic series Schlechte Verstecke (Bad Hiding Places), which was published in a German satire magazine over the course of several years and has been exhibited at various museums, is quite well known. The many different Polaroids taken since 1998 show people hiding in public spaces, under carpets, or behind curtains or street signs. However, these places are “bad hiding places”, since the people’s presence is obvious. There is a bulge in the carpet, the signpost is too narrow, the curtain translucent. The people look as if they are hiding from the camera—which, in discovering and photographing them, makes them doubly visible. And since they are Polaroids, the photographer can immediately show the discovered people how futile their attempt was. The objects in the photographs only become hiding places once we see the person; otherwise, the Polaroids would be mere still-lifes or landscapes. The sentence “We only see what we know” must here be understood backwards: “We only know what we see.” As he says himself, in his works the artist and author aims to open our perception: “By creating cracks in our perception, it is opened in these places. Basically, it is no longer functionally integrated; instead, there originates a moment of freedom in which we can suddenly start to think or experience.”